The Complex Meaning Behind One of Christmas’s Most Enduring Symbols

- The Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel, 1308/1311

One of the most recognizable scenes of Christian art, the Nativity may be surpassed in popularity only by the Crucifixion, its historical counterpoint. Nativity scenes recount the birth of Christ and his adoration, which is narrated tersely in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew. For centuries, the centrality of the subject for the Christian religion meant that it attracted the wealthiest patrons and most acclaimed artists. Many examples of the scene are deemed masterpieces of art in their own right—Duccio’s Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel (1308/1311), for example, or Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Nativity and Adoration to the Shepherds (1485)—and emblematic of major artistic movements and innovations. Below, we highlight this enduring symbol’s key developments over the last 1,700 years.

The First Nativities

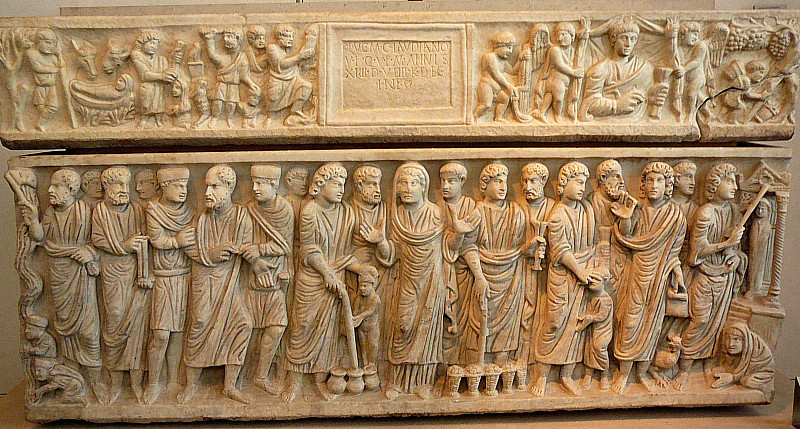

The earliest depictions of the Nativity were very different from our current conception; they typically formed part of a larger cycle narrating the life of Christ carved into the surfaces of Roman sarcophagi, thus bringing the message of death inherent to a sarcophagus in direct relationship to the most important birth in the history of Christianity.

- The Sarcophagus of Marcus Claudianus from San Giacomo in Settimiana, ca. 330

Sarcophagus from San Giacomo in Settimiana, Via della Lungara, Museo Nazionale, Rome, c. 330-340, marble. This early Nativity is very similar to the first securely dated example of the Nativity in history.

The earliest securely dated example of the Nativity scene is from 343 A.D., from a sketch of a now-lost fragment of a sarcophagus from the catacombs of Saints Marcellinus and Peter in Rome. It depicts the infant wrapped in swaddling cloths, lying in a trough close to the ground, surrounded by an ox, an ass, two shepherds, and a tree. In other words, this sculpted scene contains several of the main components of what would become the Nativity’s standard composition. Notably, Mary is absent. It was only with changes in Christianity, as her status as the human bearer of God became solidified in the next century, that she became an indispensable part of Nativity scenes.

Diverging Traditions in East and West

Over the course of the next millennium, separate traditions for the composition emerged in the East and West, accompanying the split between the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox (Byzantine) Church. The particular significance of the Nativity stemmed from the fact that it showed Christ as a human, his incarnation being an indispensable part of the economy of salvation in early and medieval Christianity. (The economy of salvation is the notion of God’s plan for the redemption of mankind through Christ’s incarnation from an earthly mother and his predestined sacrifice). Indeed, even as the Eastern Orthodox and Western iconographic traditions diverged, what remained central to both was the connection between Christ’s birth and his sacrifice, and Nativity scenes were thus elaborated to include allusions to the Crucifixion (Christ’s execution). These scenes came to communicate opposing ideas of sin and redemption, good and evil.

- Nativity, 1420-1422

Perhaps the best-known example of this development is Gentile da Fabriano’s Nativity, painted between 1420 and 1422. It shows a novel scene: Mary adoring the infant Christ, an image that emerged around 1300 in connection with mysticism and Franciscan devotional writings. There is innovation, too, in the treatment of Mary; she is shown isolated, pushed to the foreground, and elevated to the most important protagonist in the scene. The naked child appears at the center of the composition as a sacrificial offering. In this way, Gentile turns the Nativity scene into a devotional icon, with Mary acting as exemplar for the viewer’s prayer. Strikingly, this work thus acknowledges the viewer, a shift characteristic of the 15th-century interest in creating close-ups of narrative scenes and powerful, almost cinematic imagery.

Creative Nativities in the Renaissance

- Nativity, 1522/30Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

- Nativity at Night , ca. 1490

Starting with the Renaissance, artists produced incredibly diverse depictions of the Nativity, ranging from nighttime scenes (such as those of Geertgen tot Sint Jans and Antonio da Correggio) to Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s The Census at Bethlehem (circa 1605-1610), which bustles with narrative detail from his contemporary Flanders. Examples range from mystical elaborations to variations that reflected the specific interests of the patron and artist. One such creative commissioned work is The Nativity and Adoration of the Shepherds (1485), an altarpiece by Domenico Ghirlandaio in the Sassetti Chapel in Santa Trinità in Florence. It reveals the late 15th-century fascination with classical architecture—most prominently in Ghirlandaio’s use of two highly detailed Corinthian piers as a support for the roof of the shed. The work boasts vivid detail in the long retinue of the Magi approaching on the left. The scene still retains a strong symbolic character—as if drawing on the Nativity’s very origins, we see the manger depicted as a sarcophagus to suggest the altar, and Mary kneels in adoration of the infant Christ.

- Nativity and Adoration of the Shepherds, Sassetti Chapel panel, altarpiece, 1485

Strikingly dissimilar to Ghirlandaio’s idealized Mary is Caravaggio’s depiction of her in the Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence (1609). (In one of the most renowned—and still unsolved—cases of art theft, the work was stolen from the Oratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo in 1969, and has yet to be returned.) Here, Mary is depicted as a modern woman, wearing a sleeveless dress and chemise typical of working-class women of the time. Because the painting showed Mary weary from exhaustion after giving birth, it was perceived as not befitting her holiness. And since Christian theology held that Christ’s birth was miraculous and devoid of pain, the work presented a dogmatic contradiction. The angel pointing upward, proclaiming Heaven’s exaltation at the arrival of the Savior, the sharply lit figures, and the low horizon line all add to the scene’s theatricality, creating a dramatic composition that brings the viewer into the realm of the painting.

- Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence, 1609

The Nativity Today

The plastic Nativity scenes most of us are familiar with today—brought out on church lawns and domestic mantelpieces around Christmas—derive only in part from this iconographic tradition. In fact, they ultimately go back to the late Middle Ages, when they were used in religious plays. Drawing on these, the famous presepi (“cribs,” in Italian) of 18th-century Naples were elaborate, stage-like settings containing numerous figurines, typically made from terracotta, combining street scenes, costumes, and landscapes that provided realistic and lively depictions of Neapolitan life. Perhaps the most elaborate of these is the “Cuciniello Nativity,” created by a playwright in the late 18th-century, which contains over 600 miniature objects and figures.

- Nativity, 2014$10,000 - 15,000

Despite its associations with popular culture, the Nativity still proves fruitful subject matter for contemporary artists. Edward Kienholz created his Nativity in 1961 using discarded objects and ephemeral materials, a provocative gesture for what is understood as the holiest and most timeless moment in Christian history. Contemporary Colombian artist Maria Berrio’s Nativity (2014) surprises with the exotic ornamental nature of the figuration allotted to the subject. Berrio’s work is an intricate collage of patterned Japanese paper, sequins, watercolor, and acrylic paint on canvas. The scene, taking place at night, is populated by three pairs of mothers and children, and hosts a plethora of animals against a patterned landscape that imbues the scene with a dreamy, fairy-tale quality. Her work thus taps into a long iconographic history—society’s collective mythologies—to connect sacred ideas with the theme of female solidarity.

—Konstantina Karterouli

Explore more Nativity scenes on Artsy.

—Konstantina Karterouli

Explore more Nativity scenes on Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment