Vol.14 #14

New Essay

Watching the World in a Dark Room: The Early Modern Camera Obscura

Centuries before photography froze the world into neat frames, scientists, poets, and artists streamed transient images into dark interior spaces with the help of a camera obscura. Julie Park explores the early modern fascination with this quasi-spiritual technology and the magic, melancholy, and dream-like experiences it produced.

https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/the-early-modern-camera-obscura/?utm_source=newsletter

Watching the World in a Dark RoomThe Early Modern Camera Obscura

Centuries before photography froze the world into neat frames, scientists, poets, and artists streamed transient images into dark interior spaces with the help of a camera obscura. Julie Park explores the early modern fascination with this quasi-spiritual technology and the magic, melancholy, and dream-like experiences it produced.

July 31, 2025

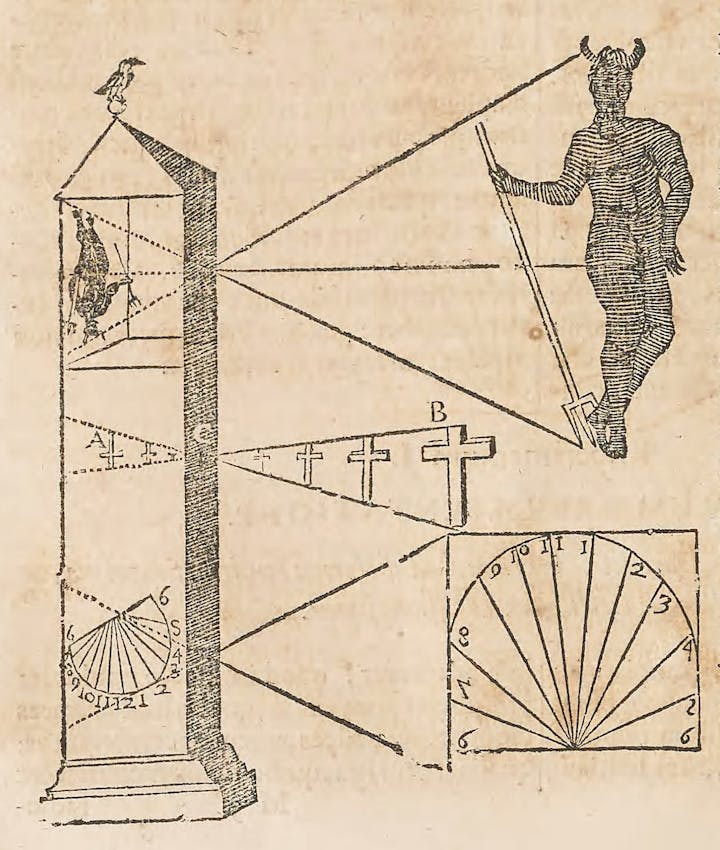

“Athanasius Kircher’s camera obscura”, illustration from Kirscher’s Ars magna lucis et umbrae (1671) reproduced in Josef Maria Eder’s Ausführliches Handbuch der Photographie (Detailed handbook of photography, 1905) — Source.

The camera obscura, a device known as the photographic camera’s predecessor, was originally the size of a room. As an artist’s aid for rendering perspective, a scientific model for understanding optics, and a source of popular entertainment, it furnished observers with all kinds of information during the early modern period. In the context of pursuing knowledge about the natural world — whether in studying the sun, the light it emits, or the very organ for seeing, the eye — alchemists, astronomers, and mathematicians turned rooms in their homes into camera obscuras for revealing what was previously invisible.

In the most rudimentary terms, the camera obscura (whose Latin name means “dark chamber”) is a dark and enclosed environment with a hole on one side. This aperture allows light to stream into the interior space, casting moving images onto the opposite wall. Because its images of external reality appear reversed, both laterally and vertically — in colors deeper than their original, with movements intact but seemingly exaggerated — the camera obscura’s projections of the world re-envision it as a dream.

One of the very first mentions of the phenomenon behind the camera obscura is tied to the viewing of a solar eclipse.1 Aristotle, while observing a partial solar eclipse in the fourth century BCE, glimpsed its reflection in the play of light that seeped through the dense canopy of a tree. Here, the “dark chamber” is not a box or a room, but the critical space between solid things. Transposing this phenomenon onto the walls of domestic architecture, early modern natural philosophers made it possible to experience the domain of one’s personal space as a realm of marvelous reversal and illusion.

First published image of a camera obscura, from Gemma R. Frisius’ De radio astronomico et geometrico liber (1545) — Source.

Frontispiece to James Ayscough’s A Short Account of the Eye and Nature of Vision (1755) — Source.

For Giambattista della Porta, polymath author of Natural Magic (1558), a book of natural philosophy and alchemy filled with magic tricks and scientific experiments, the camera obscura was a space for “see[ing] all things in the dark, that are outwardly done in the Sun, with the colours of them”.2 This evocative phrasing suggests the metaphysical happenings that the experience of being and peering inside a camera obscura offers. Della Porta’s instructions for engineering this “very pleasant and admirable” experience — among the “great secrets of Nature” — involve managing sources of light and creating the conditions by which it can be strategically channeled: “you must shut all the Chamber windows, and it will do well to shut up all holes besides”, except for one that is as wide and long as your hand.3 By covering the walls with paper or white cloth to create a viewing screen, the outside world will appear indoors, both familiar and estranged: “so shall you see all that is done without in the Sun, and those that walk in the streets, like to Antipodes, and what is right will be the left, and all things changed.”4

A spiritual dimension inheres in this experience: the notion of illumination via obscuration that surrounds the early modern camera obscura carries remnants of the medieval period’s approach to darkness as the medium for perceiving the glorious light of God. Elina Gertsman explains how nowhere was this more evident than in windows through which light, both colored and clear, flooded into the darkness of cathedrals.5 Without the dimly lit cathedral space, this transmission of light as an expression of God’s splendor would not be so keenly felt. Both cathedrals and camera obscuras share the principle that dark places form the critical environment through which transformative light and its effects can be channeled. Yet in the case of camera obscuras, it was not just light alone, but ever more wondrous projections of the world that illuminated enclosed spaces.

Illustration of a three-tiered camera obscura system attributed to Roger Bacon, from Athanasius Kircher’s Ars magna lucis et umbrae (The great art of light and shadow, 1671) — Source.

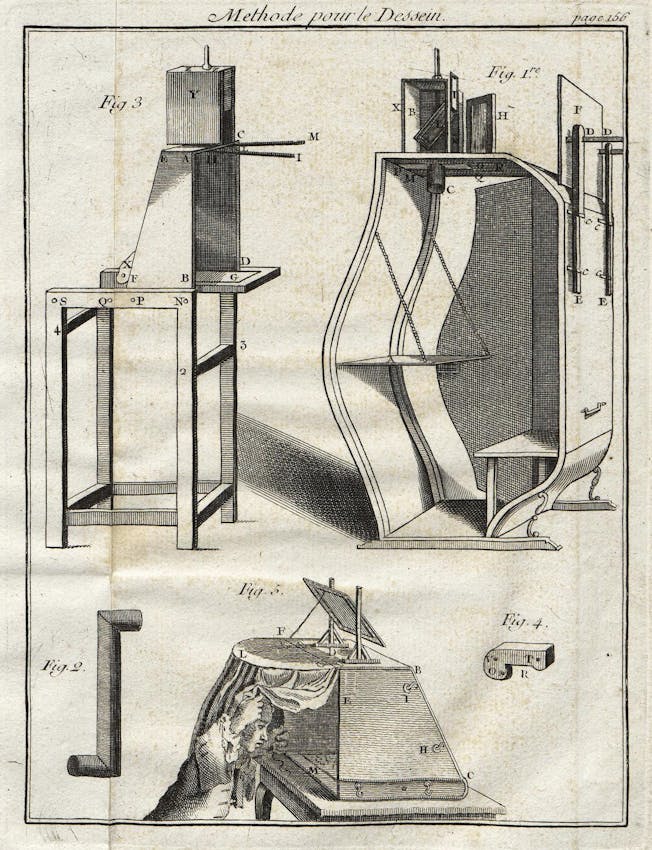

A method for drawing involving a camera obscura, from Charles-Antoine Jombert’s Method pour apprendre le dessein (Method for learning drawing, 1755) — Source.

Illustration of a camera obscura arranged to “rectify” the image of a monument or landscape, from Edmund Atkinson’s Natural Philosophy for General Readers and Young Persons (1875), a translated abridgement of Adolphe Ganot’s Cours élémentaire de physique (1851) — Source.

In the seventeenth century, portable camera obscuras emerged. Johannes Kepler, who coined the camera obscura’s name, created and used a mobile one in the 1620s. It allowed him to look at projections of the sun and other objects anywhere he desired. As described in a letter to Francis Bacon by English diplomat Henry Wotton — who visited Kepler in Lintz, Austria — this camera obscura was made from a small black tent only large enough for one person. “Exactly close and dark, save at one hole, about an inch and a half in the diameter”, it had a “long perspective trunk” with a convex glass attached to the side next to the hole, and a concave one on its opposite end.6

Through this trunk, the “visible radiations of all the objects without” were “intromitted” onto a piece of paper propped inside the tent.7 Kepler traced these intromissions with a pen, gradually turning his little tent to capture “by degrees” the landscape around him, until its “whole aspect” was recorded.8 Natural philosopher Robert Boyle, allegedly the first inventor of a handheld camera obscura, described his own “portable darkened room” in 1669, and reveled in the wonders of perceiving new aspects of the surrounding world that it conveyed with each of its turns: “upon every turning of the instrument this way or that way, whether it be in the town or open fields, one may discover new objects and sometimes new landscapes upon the paper.”9

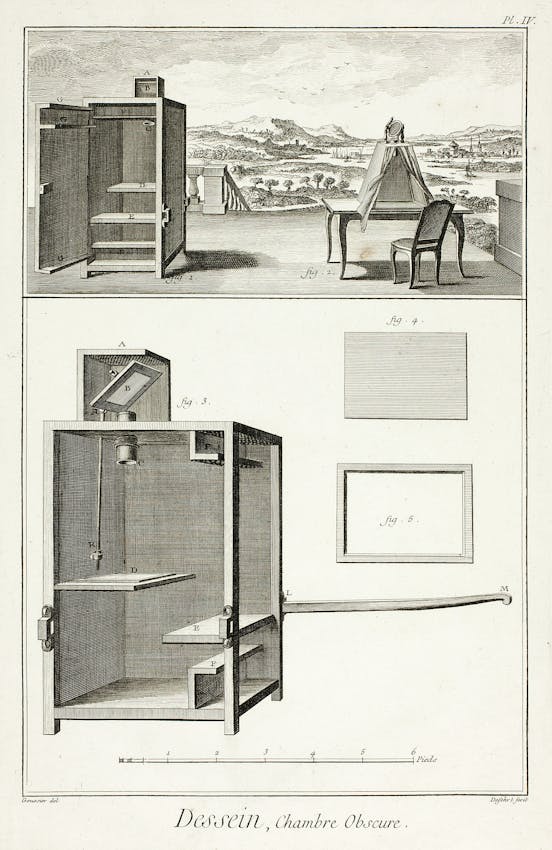

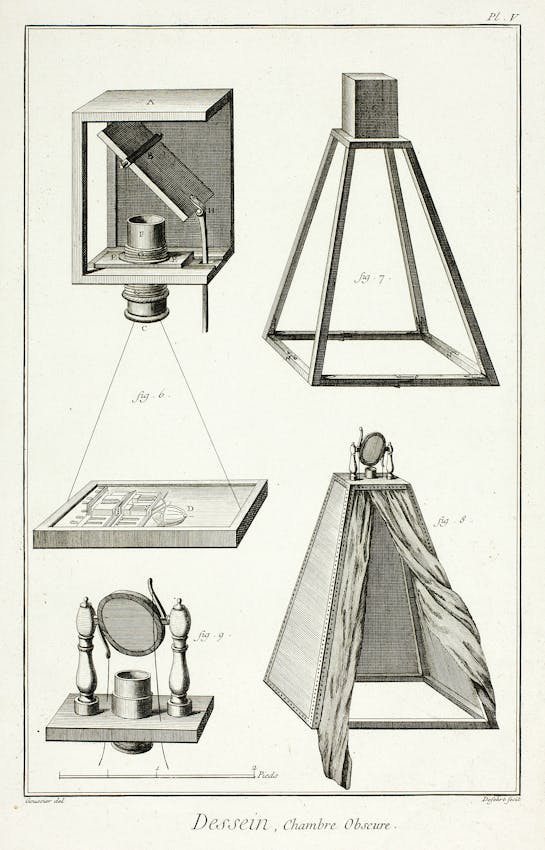

Illustration of a camera obscura by A. J. Defehr after Louis-Jaques Goussier, from the entry for “drawing” (dessein) in Encyclopédie (ca. 1762–77) — Source.

Illustration of a camera obscura by A. J. Defehr after Louis-Jaques Goussier, from the entry for “drawing” (dessein) in Encyclopédie (ca. 1762–77) — Source.

Eighteenth-century subjects were especially alive to the transfiguring potential of the world interiorized and viewed through camera obscuras — a vitality that was suggested by their popularity as a source of entertainment. Alexander Pope turned the grotto of his landscape garden at Twickenham into a camera obscura, where he enjoyed watching “all the objects” of the landscape outside move past him on its walls, including the boats of the river Thames and the people on them.10 Horace Walpole wrote enthusiastically to William Mason in 1777 about the way a portable camera obscura makes “such pictures as you never saw” and turned the very rooms and furnishings of his home into “Arabian tales”: “It improves the beauty of trees,—I don’t know what it does not do”.11 Encouraging his friend to acquire a similar device, Walpole promised it will “be the delight of your solitude”.12 Precisely for such domestic enjoyments, the entry for “camera obscura” in a 1786 encyclopedia provided instructions for fashioning a room in one’s home into one, along with the address for a London optician who sold the wooden boxes and required lenses for that purpose.

Most camera obscuras did not function autonomously but responded to the hands of their users. In the case of Pope’s grotto, built in 1723, it was with the closing of a door that the space turned into a wonder-filled realm. As he wrote to Edward Blount, “when you shut the doors of this grotto it becomes on the instant, from a luminous room, a Camera Obscura, on the walls of which all the objects of the river, hills, woods, and boats, are forming a moving picture in their visible radiations.”13 Without the gesture of shutting this door, the room would be a markedly mundane environment: “when you have a mind to light it [the room] up, it affords you a very different scene.”14

One might say that Pope acted as a magician, conjuring the “visible radiations” of distant objects to emerge upside down and in motion on his grotto’s walls. This notion is reinforced by the fact that instructions for creating a camera obscura at home continued to appear in books of magic tricks well into the late eighteenth century.15 A similar impression — that images projected by the camera obscura were illusory — was expressed elsewhere in the popular imagination, including in an anonymous poem of 1746–47 titled “On the Camera Obscura”, which appeared in a serial publication. The poem figures the device’s projections as enchanting apparitions whose vanishings leave a sense of sadness: “Pleas’d we observe—when ah! Intruding Light / From the dark Chamber drives the Noon-day Night; / Skies, Ocean, Mountains, vanish swift away, / And every lovely Phantom sinks in Day.”16

In attributing the lovely phantoms’ disappearance to the intrusion of light, this poem seems to concur with Pope’s description. But in noting that it is his “mind” that decides to introduce the light — “when you have a mind to light it up” — Pope reserves a certain artistry, the exertion of control over visual experiences. Several years after Pope described how his grotto functioned to Blount, the renowned painter Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) underscored the function that the camera obscura played in the creation of art — and did so, paradoxically, by expounding on its limitations. The owner of a portable camera obscura, now held in the Science Museum of London, Reynolds believed that the device lacked the artist’s capacity “for selecting his materials, as well as elevating his style”.17

Illustration of a camera obscura from Georg Friedrich Brander’s Beschreibung einer Camera obscura (Description of a camera obscura, 1769) — Source.

Illustration of a camera obscura from the third English edition of Adolphe Ganot’s Elementary Treatise on Physics, Experimental and Applied, translated by Edmund Atkinson (1868) — Source.

For Reynolds — anticipating later debates regarding authenticity and simulacra — choice and agency furnish the main elements of distinction between the work of a camera obscura and that of an artist in depicting a scene. Reynolds’s view on the status of “lightness and darkness” in artistic creation merits quotation at length:

If we add to this the powerful materials of lightness and darkness, over which the Artist has complete dominion, to vary and dispose them as he pleases; to diminish, or increase them, as will best suit his purpose, and correspond to the general idea of his work; a landscape thus conducted, under the influence of a poetical mind, will have the same superiority over the more ordinary and common views, as Milton’s Allegro and Penseroso have over a cold prosaic narration or description; and such a picture would make a more forcible impression on the mind than the real scenes, were they presented before us.18

By identifying lightness and darkness as “materials” that belong to artists rather than camera obscuras, Reynolds inadvertently highlights how Pope’s transformation of the grotto was very much an artistic enterprise. Just as Reynolds’ artist might do, Pope determined how much light to “dispose” in the grotto. The resulting landscape, though derived entirely from “real scenes”, is far from cold or prosaic — it has all the qualities of a landscape “conducted, under the influence of a poetical mind” and retains the ability to “make a more forcible impression on the mind”. Indeed, the scene of the “river, woods, and boats”, in their formation of “a moving picture in their visible radiations”, is as much a product of the mind’s pleasures as it is of the camera obscura carrying the image of the external world into Pope’s illuminated grotto.

Illustration of a camera obscura from a circa 17th-century (and possibly Italian) sketchbook on military art, including geometry, fortifications, artillery, mechanics, and pyrotechnics — Source.

Illustration of a soldier reproduced twelvefold from Mario Bettini’s Apiaria universae philosophiae mathematica (Beehives of universal mathematical philosophy, 1642) — Source.

While one might draw parallels with photographic technologies (both still and motion) — regarding how images are conjured by controlling an aperture — a key difference lies in the ephemerality of the viewing experience offered by the camera obscura. It captures life and its happenings as they take place, rather than preserving their images for the future. In other words, the moving images of the world it brings into its dark room are as transient as the dream state it appears to summon. And like dreams, the camera obscura could offer a new perspective on the world, to reveal things that might otherwise remain invisible. In 1764, the author of a dictionary entry on the camera obscura reflected on the ways in which the device underscores the motion of “the object itself”, such as a man walking, so that he appears to “have an undulating motion, or to rise up and down every step he takes”, in a way that could never be “observed in the man himself, as viewed by the naked eye”.19

Despite their delight, the beguiled eighteenth-century viewers and inhabitants of the camera obscura’s worlds ineluctably expressed a sense of melancholy over the ephemerality of its projected scenes. Such sentiments are apparent in the numerous poems that appeared in the period conveying regret over the eventual disappearance of its pleasing phantoms. Yet, for a brief time, the camera obscura, especially when experienced as a room, gave individuals a sense of owning their own moving images of the world, in ways that might have felt far more vivid and evocative of one’s dream life than our own experiences with cinema are felt today. The moving images it mediates come from the viewer’s immediate environment, not from a world created by a scriptwriter and producer. This aspect of the camera obscura encouraged viewers to see reality in an unreal guise, both as an inner reality and a dream world, an elsewhere that is in fact quite nearby.

Paying attention to the historical role that the camera obscura played — allowing humans a safe and enclosed environment for accessing their imaginations, the sun, and many things in between — might transform the ways we look at our own spaces of solitude. Its visual effects can make us see that our emotional and mental landscapes are inseparable from the spaces in which we live and organize our lives. The very walls that provide us with shelter can also transform the world into scenes from a passing dream. By showing the world “with all things changed”, the camera obscura reveals just how clearly we can see in dark places.

Julie Park is Paterno Family Librarian for Literature and professor of English at the Pennsylvania State University. Her most recent book, the award-winning My Dark Room: Spaces of the Inner Self in Eighteenth-Century England, posits the camera obscura as a paradigm for how interior spaces were designed, inhabited, and inscribed by eighteenth-century English writers as realms of emotion and the imagination.

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1081800)-edit.jpg?fit=max&w=1200&h=850&auto=format,compress)