'Imagine if new technologies were rooted in empathy': women, computing and radical software in Vienna

'Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991' doesn’t pretend to portray the totality of tech in art, instead taking the specific 31-year period of the title to shed light upon 48 women artists who engaged critically with computation

As soon as I left the museum and stepped into the crisply cold Luxembourg air, I whipped my phone from my pocket, tapped into the social app Bluesky, and up-posted a photo of workers at Maryland’s National Cryptologic Museum covering up the Hall of Honor of Women in American Cryptology with brown packing paper. The chilling image captured Donald Trump and Elon Musk’s anti-diversity executive order in real time as it crash-landed across the cultural landscape. Suddenly and sadly, the exhibition I had just seen, ‘Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991’, felt even more timely.

Curated by Michelle Cotton, the show doesn’t pretend to portray the totality of tech in art but cleverly takes the specific 31-year period of the title to shed light upon 48 women artists who engaged critically with computation: the start date determined by the decade that computation became more affordable through academia and institutions, filtering through artistic experimentation, and the end-date marking when the first files were available on the newly founded World Wide Web.

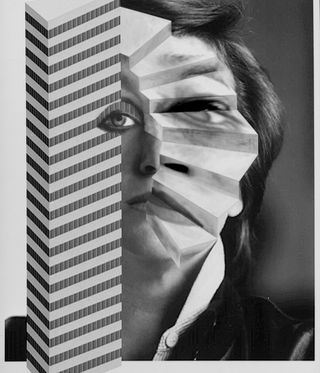

Valie Export Selbst, Portrait mit Stiege und Hochhaus, 1989

Since 1991, computation has penetrated all elements of society deeply. Including art – so deeply, in fact, it can now be hard to differentiate between analogue and digital creation. As AI audio and imagery become standard in music and film production, 3D printing integrated into traditional craft practices, and tech integral to how all creatives research, communicate, and make, it can be useful to stop, pause, and remind that it’s still a relatively recent stage of deep art history – and that the narratives we learn of that short history might be more complicated and broader than the men in charge suggest.

Laying across the floor, without a pedestal, is Grau-grünes offenes Ellipsoid by Isa Genzken. The 1977 wooden sculpture stretches and distorts a hollow three-quarter sphere into an abstraction just as Hans Holbein’s skull cut across his painting The Ambassadors 444 years before. Where that painting spoke to mediation between religiosity and Scientific Revolution, Genzken’s sculpture addresses how a transition from analogue craftsmanship to digital future might be symbiotic, not destructive. Hung on a nearby wall is a 5.47m-long computer drawing the artist gave to her carpenter – the optical and digital flattening of the sphere questioning ideas of modernist perfection and order.

Genzken’s works are presented in Zeros and Ones, the first chapter of Cotton’s five-themed exhibited journey, but one which allows for curatorial overlap so periods, themes, and media speak across open galleries to one another, offering new conversation. This is, after all, a show determined to break down simple linear narratives and transcend a patriarchal artistic canon. While deeply rooted in research and academic rigour, the exhibition is led by the aesthetic and experience of the work in a richly diverse presentation covering shifts in creative potential that maps Moore’s Law as technology progressed from binary to text to image to video – though a richly presented parallel publication allows space for Cotton and others to explore more deeply in essay and interviews.

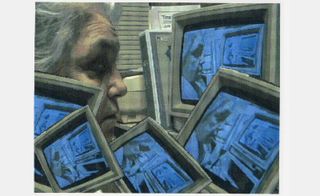

Sonia Sheriadan, Sonia in Time, 1985

Line drawings by Vera Molnár, pioneer of generative computational art, carry the romance of early experiment, especially her 1974 drawing Hypertransformation, presented on ripped plotter paper headed with the output title: ‘JOB FROM MOLNAR’. Lily Greenham’s graphics made on a home computer in 1982, using keystroke characters, sit between typewriter-made concrete poetry and digit collage with similarly playful, curious intent.

Text is used more directly by Agnes Denes, an artist celebrated now for ecological and land art works and who explored technology after abandoning painting for finding its ‘vocabulary limiting’. In Hamlet Fragmented – Wittgenstein’s ‘Pain’ (1970-71), she entered Shakespeare’s play into a computer then reduced and reformed it into lines of abstracted prose, and replaced all instances of the word ‘Pain’ with ‘Pleasure’ in Wittgenstein’s text.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Weaving recurs throughout the curation. As with many exhibitions delving into institutional archives to extract women’s works rarely considered for prior exhibitions, sewing, weaving, stitching, and crafts are transformed from what a patriarchal society may have designated as feminine labour into processes of creative exploration. Here there are also conceptual connections to the origin story of computing: Joseph Jacquard’s 1801 mechanical loom stored pattern data on punch cards, a method Charles Babbage later proposed for use with his Analytical Engine in 1837 – a machine described and theoretically expanded on by Ada Lovelace in her 1840s text Note G, admonishing ideas of artificial intelligence.

Charlotte Johannesson, Untitled, 1981-85

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Rosemarie Trockel created wool paintings on a computerised knotting machine, trained weaver Charlotte Johannesson produced digital designs on computer, and Beryl Korot’s multimedia Text and Commentary – comprising videos, woven textiles, and pictographic notations – pushed the multiplicity and potential of fusing historic craft with a digital future. It was the decade that followed these, however, when computing sunk deeply into capitalism, the home, and business, that technology became resolutely gendered, presented as a male pursuit.

This isn’t to say, however, that even if tech was marketed as a tool for men, not only male artists used it in their works, with a wall of 11 video works here from across the 1980s testament to the radical, transgressive, playful, and punchy ways women artists employed it. Together they shout the noise of the transitional 1980s: pop music videos, digitised 16mm film, video game spaces, protest politics, queering provocation, and glitching aesthetic.

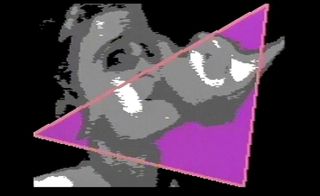

Samia Halaby’s kinetic crunchy, pixelated paintings seem to fight against romantic technoutopianism. Gudrun Bielz and Ruth Schnell’s digital transmogrification of found footage creates a between-aesthetic of awkwardness. Barbara Hammer’s No No Nooky T.V. explores how women’s sexuality and feminism enter the digital age with a full-frontal force that cuts through intervening decades and speaks directly to the swipe-dating, tickbox-desire, neoliberal-marketplace of the self that 2020s sexual identity has become.

There are other works that also now sing with poetic resonance, knowing as we do how our technoscape evolved. The House of Dust, a 1967 Alison Knowles computer-generated poem spools out of a Dot Matrix printer into a concertina pile of paper, endless four-line poems shifting words and context, foreshadowing ChatGPT and AI literature. A decade later, Ruth Leavitt created a triptych portraying axonometric plotter-outputted 3D landscapes that directly speak to the polygon landscapes millions of avatars run around in video game territories daily. Miriam Schapiro's medium may be acrylic and spray paint on canvas, but her 1971 geometric scene created digitally as a preparatory study carries a sublime lighting and hue we are now overly-familiar with through alluring, misleading property development aesthetics.

Barbara Hammer, No No Nooky Tv, 1987

This foreshadowing, or forewarning, of a world to come is most present in the final of Cotton’s themes, I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess, a line adopted from Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto and here used to explore a genderfucked sci-fi future not written by men. Here, women are centred in the frame, but on their own terms. Anna Bella Geiger’s 1969 Self-Portrait is an early compression of the self into digital form, here rendered in ASCII symbols. Valie Export’s 1989 images put her own face and body into digitally manipulated photographs. The ideas here are perhaps presented best in a prescient non-digitally-made Lynn Hersman Leeson drawing – X-Ray Woman, showing an imaginary cut-through of a female body, womb and spine connected to clockwork electronic mechanical systems, computation compressed to the biological. In a hipbone, a cogwheel is made of Vitruvian man, an about-turn of gender structures that have become embedded into the digital since 1966, when the work was made.

Within the origin story of Meta, now one of the world’s largest and most consequential companies, is Mark Zuckerberg’s sophomore side-project Facemash, a website made to rate the looks of women on the Harvard campus. When not wielding chainsaws on stage at the Conservative PAC, giving fascist salutes, or undermining democracies, Elon Musk is pushing a pronatalist agenda that seems to solely see the female body through biopolitical usefulness. The Silicon Valley they and others preside over is one where men are the geniuses, thought-leaders, instigators, and leaders.

Valie Export, Stand Up Sit Down, 1989

A sheet of brown packing paper urgently hung over the faces and legacies of female, Black, brown, and queer people who have created technological histories we all benefit from – but could more equitably benefit from – will not stop their stories. Radical Software is an important part of the multitude of stories remaining central, but more than that, perhaps also provoking and presenting alternative models for our shared technological futures. We are all becoming cyborgs, but in whose image do we get to enact our virtuality, avatars, and digital selves. In these works, we are reminded of utopian, complicated futures, full of ambition and excitement, sure, but also care, community, agitation, politics, agency, and identity.

Stopping to pause and reflect on the impacts of technology on our lives is also useful right now. Techbros have increasing control over society: Elon Musk is parading around the White House; three decades of Jeff Bezos’ Amazon growth has seen an online bookshop become a gigastore of $600bn revenue; TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook algorithms affect elections, mental health, and taste. Seven of the ten richest people in the world made their estimated $1.4 trillion fortune from technology. They are all men.

‘Radical Software’ seeks to remind that there is more to both culture and technology than the few men who rise to the top, the 100-plus works on show don’t just celebrate the rich roots of computational art, they invite us to imagine what societies might have created (or still might) if the technologies we inject into our world were rooted more in empathy, care, curiosity, and exploration than the than hypercapitalism and authoritarianism of today.

‘Radical Software’ is showing at Kunsthalle Wien until 25 May 2025

Gudrun Bielz und Ruth Schnell, Pluschlove

Will Jennings is a writer, educator and artist based in London and is a regular contributor to Wallpaper*. Will is interested in how arts and architectures intersect and is editor of online arts and architecture writing platform recessed.space and director of the charity Hypha Studios, as well as a member of the Association of International Art Critics.

No comments:

Post a Comment