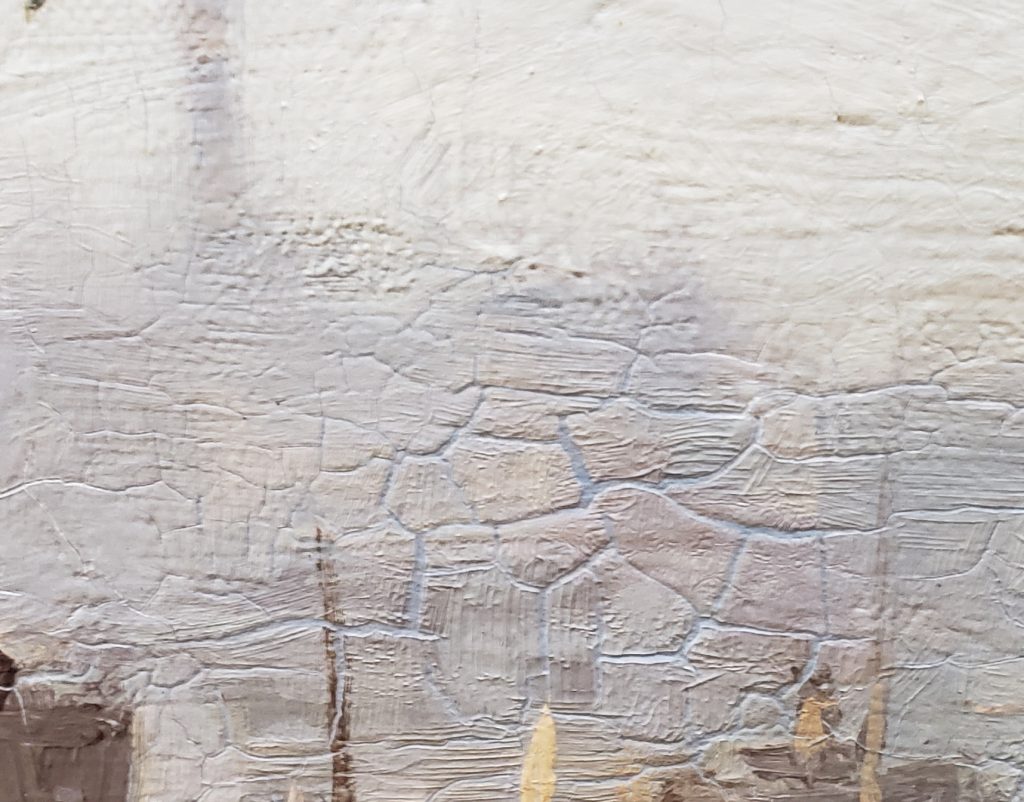

How To Safely Navigate The Art Market: Cracks in the PaintAugust 25, 2019 After I wrote my initial article on water and humidity (many years ago), one of our readers followed up with the following question: If I see a painting and there are cracks in the paint, can I then assume that the reason for this is that there has been some damage from moisture?  The answer to this question is: No. Moisture damage is only one of the possible causes. To begin with you must keep in mind that much like the human body as a work of art ages, cracks will begin to form. Works of art are made up of many layers (canvas, gesso, pigments, varnish, etc.) each of which will react differently over time to various changes in the climate. For instance, a work on canvas will expand (loosen) and contract (tighten) as the temperature and humidity levels change. I am sure that many of you have seen a painting where the surface looks wavy. Most often, this is caused by the expansion of the canvas due to higher than normal levels of humidity. As the humidity levels return to normal, the canvas will contract and become flat again. Should these changes continue to occur, over time they will begin to affect the various layers of the painting and cracks will appear. These cracks are a visible sign that a work of art has some age to it and usually present themselves as a network of straight or slightly curved lines that will be visible on both the back and front of the painting. The front of the canvas will appear to have raised lines while the back will have corresponding indented lines Many times these age cracks, as they are called, are not generally considered a serious condition issue and can be removed by a qualified conservator who will perform a vapor treatment to relax the various layers (basically flattening them). Once the treatment is completed, they will either spread a thin layer of glue on the back and re-stretch with work (if the cracking wasn’t too severe) or will re-line the painting in order to keep the cracks from reappearing. This type of re-lining is often termed as cosmetic.  The next, most common, type of cracking is referred to as craquelure. This term is used to describe the network of very fine, small, cracks that also begin to appear as a work of art ages – they are also referred to as ‘spidering’ since the resulting appearance is similar to a spider’s web. There is nothing wrong with these cracks and only need to be addressed if the edges are beginning to lift. It is important to remember that just because a work of art appears to have craquelure, or even age cracks, does not guarantee that it is old … forgers know how to replicate these effects on newer works of art. Stretcher bar marks are another common sight on older paintings. Over time, the canvas will expand and contract. During times of expansion it may touch, and rest, against the wood stretcher bars. Over time a crease or line will form that follows the edge of the stretcher bars. These marks display themselves as straight horizontal and/or vertical lines on both the front and back of the canvas. Again, a qualified conservator can treat them, and many times lessen or completely remove their appearance from the paint surface. This would also be considered a cosmetic procedure.  Impact cracks are also somewhat common and present themselves as circular cracks on the canvas … their appearance is similar to the ripples one sees after throwing a stone into the water. These cracks, which can take years to develop, are a sign that something hit the canvas at the center of the innermost circle (corner of a piece of furniture, etc). Crackle is a term used to describe the network of small cracks that can appear in any layer of the painting. Crackle in the structural layers of the painting, including the paint surface, would be considered more serious than crackle in the protective varnish layer since the varnish can be easily removed by a conservator and replaced with a new one; thereby completely removing the crackle. Now I will touch on a few of the more serious cracks.  The first of these are what we refer to as pigment separation — a more serious version of craquelure. Instead of a fine network of straight and slightly curved cracks, now the work of art displays wide cracks where the paint has split open and exposed the under-paint or ground. Another very similar problem is referred to as alligatoring. As the names suggest, the appearance of these cracks is much like the skin of an alligator … wide areas where the paint surface, during the drying process, has shrunk and the lower layer is visible. A related issue is Bitumen — a dark colored paint made from coal tar that was often used in 19th Century Victorian paintings. As the pigment ages, a chemical reaction in the paint causes it to shrink and the area looks as though it is blistering. A good conservator can repair any of the above-mentioned problems by filling in the low points (or spaces) and in-painting those areas to match the surrounding colors. However, as you can guess, the work of art will now have areas of in-painting and its value will be altered depending on the severity of the problem and how much restoration was required. It is interesting to note that there are some artists who’s entire body of work is plagued by these problems. The American artist Albert Pinkham Ryder is a great example, and if you want to own one of his works, these are condition issues you will have to live with. For artists where these issues are seen occasionally, it is best to stay away from the problem works and concentrate on those in better condition. Crazing, which usually develops due to excessive heat, is another serious issue and presents itself as small ridges in the paint layer. If a work heats up to the point where the paint becomes pliable and, at the same time, the canvas begins to shrink, the paint surface will be pushed together forming ridges. If this happens, the painting’s surface has been altered and will, or really should, lessen its value. There are ways for a conservator to reduce, or even eliminate, the visual effect of this problem, but all require further alteration of the painting’s surface. I personally remember watching a conservator place a 19th century painting by Monchablon, that had some crazing, on the hot table and heat it up to a point where the paint had begun to liquefy (I know that sounds crazy). Then, while still on the hot table, they were able to press down, with a small tool, on the crazed areas and completely remove them. Not the best thing to do to a painting as this procedure also alters the artist’s original work. In the end it is important to remember that condition is a very important element of a work’s value and to the untrained buyer, many of these problems can be masked. Make sure you ask questions about any work you are considering and try to understand its condition. Not all paintings are in pristine (untouched) condition and some level of restoration is acceptable, but do try and stay away from those works that have extensive condition problems … especially those with large areas of pigment separation, alligatoring, crazing and/or bitumen. | MORE ARTICLES |

No comments:

Post a Comment