GUIDE

How to read philosophy

The first thing to remember is that the great philosophers were only human. Then you can start disagreeing with them

by Charlie Huenemann

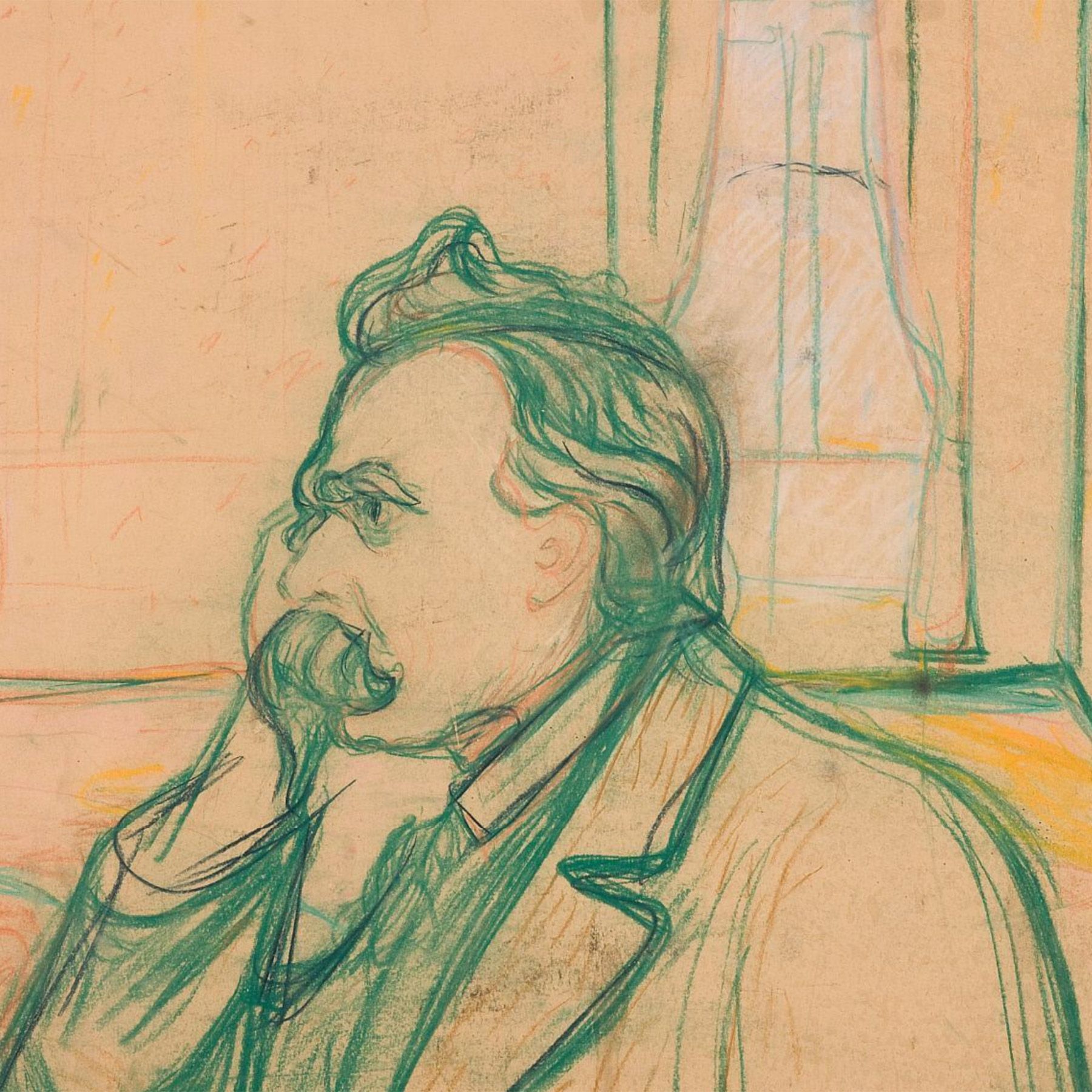

Friedrich Nietzsche (1905-06) by Edvard Munch. Courtesy the Munch Museum, Oslo

Need to know

It might seem daunting to read philosophy. Giants of thinking with names like Hegel, Plato, Marx, Nietzsche and Kierkegaard loom over us with imperious glares, asking if we are sure we are worthy. We might worry that we won’t understand anything they are telling us; even if we do think we understand, we still might worry that we’ll get it wrong somehow.

So, if we’re going to read philosophy, we need to begin by knocking those giants down to size. Every one of them tripped and burped and doodled. Some of them were real jerks. Here’s Arthur Schopenhauer on his fellow German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, for instance: ‘a flat-headed, insipid, nauseating, illiterate charlatan, who reached the pinnacle of audacity in scribbling together and dishing up the craziest mystifying nonsense.’ I’m not sure whether this paints Schopenhauer or Hegel as the bigger jerk.

The point is that each giant of philosophy was a human being trying to figure out life by doing just what you do: reading, thinking, observing, writing. Don’t let their big words intimidate you; we can insist that they make sense to us – or, at least, intrigue us – or are left behind in the discount book bin. They must prove their worth to us.

But what might that worth be? That is, why read philosophy in the first place? The chief goal is, simply, the improvement of your own soul. No one should read philosophy just to sound smart, or intimidate others, or have impressive books on the shelf. One should read philosophy because one wants a better mind, a better spirit, and a better life. (Or, at least, one wants a better understanding of why none of these things are possible, or why none of them matter; philosophy leaves no possibility unexplored.) The hope is that these so-called giants are offering us some guidance or companionship in this regard.

The most stirring reason for reading philosophy was given by Bertrand Russell at the end of his short book, The Problems of Philosophy (1912):

Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions, since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination, and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes its highest good.

Reading philosophy gives us richer perspectives, casts us into deep wonder, and helps us grapple with the biggest questions a human can ask. It is a heady call to action – and one that can only be met by diving in to the works themselves. So: how does one read philosophy?

Think it through

Reconsider your expectations of philosophy

To this day, there are bookstores with sections titled ‘Philosophy’ that include titles like The Seven Secrets to a Happier Life, or Get Your Sh*t Together, or Living With Your Heart Wide Open. These are self-help books, and some of them may actually prove helpful in giving you a better perspective to overcome or live with the obstacles in your path. Maybe you should make your bed every morning, or take a cooking class, or see each person as another authentic self. That’s wonderful. Everybody needs a helpful nudge from time to time, and probably every self-help book has helped someone somewhere.

But as helpful as self-help books are, they are not philosophy. Philosophy typically raises less personal questions, such as whether time is real, or whether humans can exempt themselves from laws of nature, or if a person is just what their brain does, or whether we have moral obligations to strangers. And philosophy does not merely want to know the answers, but also why they are the best answers, and why the other answers are wrong.

Yes, wrong. Philosophy is not afraid to say it.

At a very general level, self-help books help you with the problems you shouldn’t have; philosophy helps you with the problems you should have. (There is some overlap, of course: some philosophy books can actually help you overcome problems you shouldn’t consider as problems, and some self-help books draw attention to things in life you should regard as problems.) But more generally, philosophical problems are the ones that unavoidably come along with being conscious. If you can think, you have problems: this is why there is philosophy.

Heidegger said of Aristotle that the only biographical facts he needed to know were that he was a human being who was born, who worked, and who died. All the other features of a life are accidental. One shouldn’t expect from a book of philosophy any counsel or advice that wouldn’t apply equally well to any human being who has lived.

But how does one get started? What books are good to begin with? Philosophy isn’t like mathematics, where people generally agree that you need to start at one place and take a sequence of steps that steadily build upon one another. It’s more like a hallway with many conversations underway. A beginner might find a general introduction useful, just to get a map of the hallway, so to speak. Some specific recommendations can be found in the Links and Books section below, but perhaps the most important point to bear in mind is that there’s no single or best way to begin. Start anywhere, and follow your interest wherever it goes.

Philosophy requires active, adversarial reading

Dogs must think that we slip into comas when we are reading books because we hardly move at all. Only our eyes move as we scan left to right and back again, occasionally flicking a page or scrolling ever downward, frozen in place while words pour into us and form themselves into something like ideas. Indeed, we typically gauge good writing as the kind that requires the least degree of movement on our part. If what we read causes us to frown, or go back a page, or scrunch up our eyebrows and gaze distractedly at the ceiling, then that stuff is bad writing.

By such a measure, philosophy is often very bad writing indeed because it demands exactly this kind of activity. It’s hard to turn the words in a philosophy book into ideas. You have to keep track of unusual terms, careful distinctions, and pivotal examples and general principles. If you are doing it right, you are using a pen, pencil, stylus or quill to mark important or puzzling passages, to underline important claims, and to carve ‘???’ or ‘?!’ next to the confounding things philosophers are wont to say. (Far from a coma, your dog should think you’re in a fight with your book.)

Philosophy books should be approached multiple times. You might first read through the work relatively quickly, so that you have a cloudy idea of what is being said. Then you should read it again, with attention to detail: this is when you should mark up the book, or take notes, so that you can understand more clearly what is being said and why. For some books, you may either feel done or lose interest at this point. For others, you will want to repeat this process: read quickly again, read slowly again, repeat.

It has been said that there are ultimately two replies to any philosophical claim: ‘Oh yeah?’ and ‘So what?!’ He was right. These are the two questions that you should have at the ready whenever you are reading a philosophical text. You should be thinking of counterexamples to the general claims that are made, or other possible explanations, or asking whether the philosopher is handling similar cases consistently. You should also be asking whether those claims have any important consequences and whether your life should change at all if you were to agree. Insist that the philosopher make a compelling case for your attention.

This means taking an adversarial approach to philosophical texts. You want to be the tough-minded, sceptical judge before whom some hapless attorney is making an argument in a controversial case. But it is also true that this tough-minded approach must be blended with some degree of interpretive charity. In all likelihood, the philosopher you are reading is not an idiot; so if your reading of the text implies that the philosopher is making idiotic claims, then the problem could be with your reading. Interpret the arguments and the claims in the most favourable light. If problems remain nonetheless, then you can get judgy.

Notice how different this is from many other types of reading. It would be perverse to read a novel while scribbling ‘Oh yeah?’ and ‘So what?!’ in the margins. Many nonfiction books aim to inform you about history or science or politics or whatever, and they are not trying to convince you of something so much as give you the basic idea of what’s true. Of course, there may be times when you will want to ask: ‘Oh yeah?’ in response to dubious claims in these books. But philosophy books must be read with these questions in mind, because you simply won’t understand them unless you take this active, adversarial attitude. You can’t get strong by watching others at the gym. You have to do some lifting yourself.

Besides, active reading will help you to retain more of what you read. Unworked books are soon forgotten.

Philosophy is dialogue

Some philosophical books really are dialogues of characters conversing with one another. They read like plays, though if your local high school puts on a production of Plato’s Theaetetus – a lengthy dialogue about knowledge and judgment – I’d recommend staying home. Other books are straightforward treatises covering some topic in exhaustive monologue. But all philosophical works, even the monologues, are dialectical. They are conversations between someone making a claim and someone raising objections to that claim, or pressing questions to deeper levels. Indeed, philosophical books can become very complicated conversations, because not only are there multiple voices present in the author’s text, but now you have joined the conversation as well, conversing with those voices and your own voices. You and a book are now having a party.

Many philosophy books record the results of philosophers talking to themselves. The French philosopher René Descartes in his Meditations (1641), for example, argues with himself ceaselessly, paragraph after paragraph:

I will attempt to achieve, little by little, a more intimate knowledge of myself … Do I not therefore also know what is required for my being certain about anything? … Yet I previously accepted as wholly certain and evident many things which I afterwards realised were doubtful … But what about when I was considering something very simple?

Descartes is giving himself the ‘Oh yeah?’ treatment. In a way, it is a rhetorical ploy, since he is trying to make it seem as if anyone who is clear-minded and honest with themselves will drift inexorably into the charmed circle of Cartesian metaphysics. But never mind that; it is still a brilliant work of dialectical reflection. The reader is supposed to be carried along in this dialogue, thinking of the same objections that Descartes gives expression to and then tries to answer. But a clever reader such as yourself will probably ask some questions Descartes doesn’t raise, or you will come up with alternative answers he didn’t think of. So you have a part in the dialogue too. Take notes to keep track of it all.

This dialogue is essential to philosophy. Maybe it is essential to all thinking. We raise ideas, ask questions or pose problems, revise or extend those ideas, face new challenges, propose new ideas, and we keep batting questions and answers back and forth in the tennis court of the mind until we can’t think of anything new to say. But philosophy lives in this energetic back-and-forth, picking up on missed possibilities or raising new questions or going back to insert some distinctions before reaching disastrous conclusions. That’s the philosophical method: keep the conversation going, changing, evolving.

Philosophy, as I would define it, is grappling with ideas at the borders of intelligibility. As soon as the questions become fully intelligible and tractable, then a new discipline emerges, like physics or biology or psychology. But while we are still wrestling back and forth over what seems to be true and what seems impossible in matters we cannot see in high resolution, we are doing philosophy. There really is no way to proceed except in a dialectical, back-and-forth manner.

In reading philosophy, you want to be sure to take up the dialogue. To that end, you should keep a journal to explain to yourself what you think is being said in the book, what you think about it, what you’d like to ask the author, and what you would like to tell them (even if it’s impolite). As you make your thoughts explicit on the page, you will learn more about what you yourself think. Sometimes we don’t know what we think until we hear (or read) ourselves saying it. Taking notes in a philosophical dialogue is a way of learning new things about your own mind and your own experience. When you return to that blasted book for a third or fourth time, you will be armed with new questions and perspectives to bring into the conversation. It will be a new reading of it.

It has been said that you are never done reading a great book because each time you read it you become a different person. That may be an exaggeration, but there’s something to it. It is also sometimes said that as you read a great book, it reads you. That is to say, you may begin to understand your own life anew through the concepts the book has suggested to you. This is the inevitable result of any genuine dialogue. That’s when philosophy is at its best.

Philosophy is about you

Philosophy is not specifically about your problems at work, as in the self-help genre, or how to manage the contacts in your phone, or whether to drop all social media – though all those things might be illuminated by philosophy. It is about your life as a human being.

Imagine being sucked into a time vortex and ending up next to some person from ages ago. Once you work out a common language, could you become their friend? Could you share with them your worries, your hopes, your ideas, your faith? Of course you could. But your conversation would have to be between human and human, not between post-industrial educated technocrat and caveman. You could be friends based only on your shared humanity. Indeed, it might be the best friendship you ever had, because there wouldn’t be all that trivial crap standing in the way of a genuine conversation.

Many of the self-help books referenced earlier focus on the importance of finding out who you really are, as opposed to all the ways others have defined you. One might do this by gazing inward or trying out a new lifestyle. Philosophy urges a different approach. We can find out who we are by engaging others in conversation about who we might be. Plato, Aristotle and Avicenna all have ideas about this; so do G E M Anscombe, Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche; and so do Nagarjuna, Lao Tzu and Kwasi Wiredu. In the end, if we are to be anybody, we will be adopting some sort of definition coming from somewhere. Philosophy offers the opportunity of exploring multiple definitions and trying to find yourself among them – this is the shared activity of all philosophical reading.

Make use of secondary sources

The fact of the matter is that we live in an excellent time to be introduced to philosophy. YouTube abounds in explanations of philosophers and their ideas, and, though every video should be met with some measure of scepticism, many serve the broad purpose of getting us into the proverbial ballpark. Philosophy Tube, for example, offers witty and provocative explorations of philosophical questions. Many podcasts are also useful orientations: The Partially Examined Life, Very Bad Wizards, Philosophy Bites (co-run by the Aeon+Psyche editor Nigel Warburton) and Peter Adamson’s brave and brilliant History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps – and many others – all provide casual entryways into philosophy. Let us not be book snobs: Plato himself thought that real philosophy takes place only in live conversation, and a written text is at best only an imitation of the real thing. (And yes, he wrote that down in a text.)

There is also a wide world of secondary sources at your disposal to help tease out the intricacies of great philosophical texts: don’t hesitate to use them. One nice thing about a discipline as old as philosophy is that textbooks don’t exactly go out of date, and sometimes some old introductory textbook from 1970 can provide a nice overview of a tangled set of questions. As you read more and more, you might discover the shortcomings of older secondary materials, but you should count that as a win: you are developing your own philosophical perspective.

Finally, one should also never underestimate the value of friends as secondary sources (or even primary sources). If you form a reading group and talk about the great books you come across, you will learn how to interpret, object, argue and change your mind – all essential tools of any philosopher (as well as any human being).

Key points – How to read philosophy

- Reconsider your expectations of philosophy. There is a certain mindset that helps when approaching philosophy – prepare to confront questions without answers, and problems without solutions.

- Philosophy requires active, adversarial reading. To get the most out of reading philosophy, keep a pencil in hand, mark up your book, and challenge the author every chance you get.

- Philosophy is dialogue: the back and forth, cut and thrust of ideas is what makes it exciting. When you read, pay attention to the dialogues that make philosophy. And be sure to take part as well.

- Philosophy is about you. Philosophical conversation (with the book, or a friend) will always tell you more about yourself – who you are and what you think about the world. Philosophy is, in many ways, a process of self-discovery.

- Make use of secondary sources. This is a great time to begin philosophising because there is a wealth of sources out there that make the greats accessible.

Why it matters

I am sorry to be the one to break it to you, but you are mortal. Before your end, though, you should eat right, exercise regularly, make friends, and be helpful to strangers. You might also take some time to wonder what it means to exist, what reality really is, whether there’s a god, and whether you have any purpose in living a human life. Answers are not guaranteed, but trying to find them may help you to feel as if you haven’t missed out on your one chance to understand what it’s all about.

Reading philosophy is the best way to grapple with these big questions. Again, no answers are guaranteed – or rather, too many answers are guaranteed! – but the conversations with great philosophers will help you discover what the big questions mean to you. All you need is time, some curiosity and a library card.

Plato said that philosophy begins in wonder. Wonder about what? It could be about your own consciousness; about whether any part of you will survive the death of your body; about the nature of love or beauty; about whether humans are always bound to mistreat one another, or whether our natures can be improved; about scientific knowledge, and whether everything can be understood. Human experience gives us plenty of occasion to wonder.

But in everyday life, this sort of wonder is often discouraged because it is seen as impractical. ‘There are no answers to these questions,’ we may think. ‘Empty speculation. Each to their own.’ So should we not wonder? Should we pretend that these questions don’t matter, merely because their value is extraordinary? Or should we seize the opportunity, at some point on the path from cradle to grave, to wonder over the most profound questions we can ask?

Links & books

People are interested in reading philosophy for different reasons. Some like quick and juicy puzzles, like the infamous trolley problem or questions about transporters. David Chalmers’s recent book, Reality+ (2022), offers a splendid array of puzzles of this flavour while raising provocative questions and insights about the reality of virtual reality.

Other folks might like to fill in some gaps in their knowledge in the grand history of ideas. Will Durant’s classic The Story of Philosophy (1926) offers an overview of several canonical philosophers. It’s the book I most frequently recommend to someone who is starting out reading philosophy and wants a roadmap.

Bryan Magee offers a flashy update of Durant in his book The Story of Philosophy: A Concise Introduction to the World’s Greatest Thinkers and Their Ideas (2nd ed, 2016). One can easily advance from Durant’s or Magee’s overviews to collections of the classic works themselves, such as provided in Steven M Cahn’s anthology Classics of Western Philosophy (8th ed, 2011).

If one is interested in what on earth contemporary philosophers are up to, Richard Marshall provides scores of straight-speaking interviews on his site, 3:16.

On the more general topic of reading, a classic instruction manual for active reading is How to Read a Book (1940) by Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren. It’s definitely old-school in style and flavour, but it is a nostalgic delight to read such clear and wholesome writing, and the advice is undeniably useful for reading philosophy books.

Some nuts-and-bolts advice about reading philosophy can be found on this student blog from the University of Edinburgh. For anyone who would rather watch a video, similarly good advice is offered in the YouTube video ‘How to Read Philosophy in 6 Steps’ (2016) by Christopher Anadale.

Last, but far from least, Justin E H Smith’s book The Philosopher: A History in Six Types (2016) will broaden your definition of what ‘counts’ as philosophy and what we may be interested in when we read philosophy. It is a useful corrective to anyone who wants to gatekeep the pursuit of wisdom.

My thanks to Kris Phillips, Elijah Millgram and other participants in the Intermountain Philosophy Conference (held in February 2022) for helping to guide my thinking about writing about reading philosophy, and thanks to Sam Dresser for so many valuable suggestions.