| ||||||

| ||||||

|

- 7:00 AM

How Natalie Portman and her Angel City FC cofounders are changing the game for women’s soccer

Professional women’s soccer has been undervalued and under-resourced. The high-profile owners of L.A.’s new NWSL team are rewriting the rules of the game.

Just blocks from Amazon Studios in Santa Monica, next to a startup that’s developing high-protein, low-carb bagels, is the headquarters of one of L.A.’s buzziest new brands. Inside, it’s light and airy, with standard-issue startup touches like exposed pipes and industrial light fixtures, plus a few dogs peeking out from under desks.

But there are a few details that you won’t find anywhere else: a plastic-wrapped flat of neon-colored Gatorade near the front entrance and a wall dominated by photos of women—goofy candids of Angel City FC soccer players, their fans, and the new team’s mostly female staffers, many of whom are gathered around desks nearby.

The conversations they’re having on this February morning are undoubtedly unlike anything being talked about at neighboring offices too. News has just broken that members of the national women’s soccer team, which represents the U.S. internationally and won the 2019 World Cup, have agreed to a historic $24 million equal pay settlement with the sport’s national governing body, U.S. Soccer Federation. In addition to awarding back pay to current and former players, U.S. Soccer also committed to equalizing compensation between the women’s and men’s national teams.

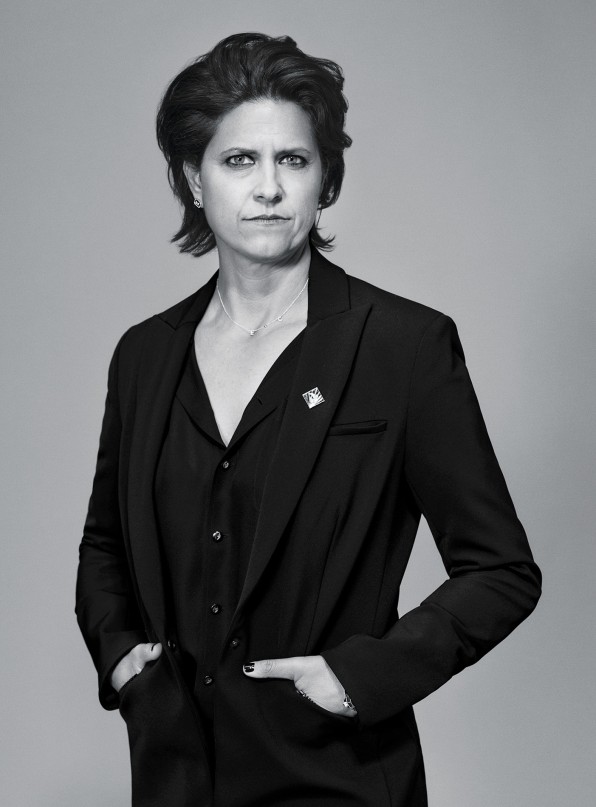

“It’s a big statement for women’s sports,” says Angel City president and cofounder Julie Uhrman, sitting on a folding chair in a sunlit yard next to her club’s office. The women’s national team gets more viewers and attention than the men’s team, she points out, and it drives fans to purchase more merchandise. “Seeing that finally recognized in pay equity is long overdue.”

Equity—in income and opportunity—happens to be the mission of her club, one of two expansion teams that is embarking on its first season this spring in the 10-year-old National Women’s Soccer League, or NWSL. Since its founding two years ago, Angel City has garnered headlines for its star-studded ownership group. Uhrman, who has a background in tech and entertainment (she previously oversaw streaming services for Lionsgate and business development for VR startup Jaunt), cofounded the team with actor Natalie Portman and Kara Nortman, managing partner at Upfront Ventures, L.A.’s largest venture capital firm. Reddit cofounder and venture capitalist Alexis Ohanian is the team’s lead investor, and the club’s other backers include A-list actors (Eva Longoria, America Ferrera), tennis legends (Billie Jean King, Serena Williams), and 13 former national team members (Mia Hamm, Abby Wambach, Julie Foudy).

The group coalesced around the idea that their undertaking was bigger than soccer. “We love soccer,” says Portman. “But we also have a secondary mission, which is to push forward the state of conditions for female athletes.” For Angel City, that has meant creating an ownership model that asks investors to act more like founders and engage with the team at every level. The club has also developed an industry-first sponsorship program to draw in brands that are not traditionally aligned with sports and is finding fresh ways to support its world-class players on and off the pitch.

In a league where the salary minimum is $35,000 and the maximum is $75,000, there’s a lot of work to be done. (Even reserve players in the men’s Major League Soccer make a minimum of $65,500.) But it’s not just about the money. In 2021, male head coaches at 5 of the league’s 10 teams were fired or resigned due to claims of inappropriate conduct, including racist remarks, sexual misconduct, and verbal abuse. In September, The Athletic published a bombshell story in which several players accused North Carolina Courage coach Paul Riley of sexual coercion and making inappropriate comments. (Riley, who was fired, has denied the majority of the allegations.) “Burn it all down,” wrote national player and Seattle’s OL Reign captain Megan Rapinoe on Twitter. “Let all their heads roll.” Lisa Baird, once lauded for her success growing the league as commissioner, resigned after it emerged that she had known about the Riley claims for months. General counsel Lisa Levine also stepped down. Two investigations into what happened are pending.

NATALIE PORTMAN, ANGEL CITY COFOUNDERTHIS IS AN OPPORTUNITY TO MAKE A CULTURAL SHIFT.”

Underlying all this is the fact that the NWSL is the third incarnation of a professional women’s soccer league in the U.S. Earlier versions both folded due to financial instability. That legacy has had a lasting impact. Fear of hurting the league or doing anything that might put the brakes on its momentum “can perpetuate a culture of silence, which can perpetuate a culture of abuse,” says Meghann Burke, executive director of the NWSL Players Association.

Angel City is poised to play a key role. First, though, it needs to prove its business model. “I have the best athletes in the world playing a global sport in a city of champions,” says Uhrman. “We are going to build the club authentically, thinking about it as a brand.”

The story of Angel City’s sky-high ambitions begins, fittingly enough, on an airplane. Nortman was with her husband and three kids on a flight from Los Angeles to Boston in July 2019, texting with Portman. The two had become friendly through their interest in soccer and advocacy work. Portman is a founding member of Time’s Up, and Nortman helped found All Raise, an organization working to support female and nonbinary founders and funders. From the plane, Nortman sent Portman a several-paragraphs-long missive about the potential for women’s soccer to build a more mainstream audience. “Rant now done. Haha,” she concluded.

Portman’s response was simple: “We should bring a team to L.A. together.”

Nortman thought Portman was kidding. “I’m a venture capitalist,” she says, and therefore conditioned to think big. “But I never allowed myself to dream that we could go start a soccer team.”

Portman, however, was serious. “It seemed completely doable when we started understanding how undervalued these teams are,” she says. “This is an opportunity to try and actually make a cultural shift.”

Once Nortman started to look at the data, she agreed. She saw a global fan base for soccer that’s nearly 50% women. She saw NWSL viewership steadily increasing, even with little promotional support. She saw opportunities for new distribution channels over platforms like Twitter and Twitch—and lots of room to sell merch. And Southern California, which easily supported two men’s teams with more than 20,000 fans a game, was already home to a disproportionate number of top women players. The market was there.

KARA NORTMAN, ANGEL CITY COFOUNDERI NEVER ALLOWED MYSELF TO DREAM THAT WE COULD GO START A SOCCER TEAM.”

“I didn’t even know that there was a women’s professional soccer league,” admits Uhrman, who grew up in Los Angeles. But she was definitely interested. Five days later, Uhrman, Portman, and Nortman were in the stands of an “El Tráfico” matchup between Los Angeles’s men’s soccer teams, the LA Galaxy and Los Angeles FC. Uhrman was impressed by the supporter groups that had coalesced around them. It seemed natural that they could build a similar fan base for a women’s team. Uhrman saw a woman in the stands waving a flag that said “Bring NWSL to LA.” She took that literal sign as a sign.

Uhrman began studying how other soccer teams operate. She wanted to understand, she says, “What are the economics of running a club? What are the revenue drivers? What are the cost drivers?” More pressingly, though, she needed someone to buy a team.

Like more than 260 million people around the world, Ohanian had watched the U.S. team’s victory in the 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup final. He had been with his wife, Serena Williams, and daughter Olympia, who was running around in an Alex Morgan jersey. “I commented, like every parent does, ‘Olympia, one day you could play on the World Cup team,’ ” he recalls. “And, my wife, without missing a beat was like, ‘Not until they pay her what she’s worth.’ I was like, ‘Okay. Challenge accepted.’ ”

When he heard what Uhrman, Nortman, and Portman were planning, he offered his backing and advice. (Along with her parents, Olympia, then 2, became an investor in Angel City, making her the youngest coowner in pro sports.) Ohanian suggested they look for investors who would function like the entrepreneurs in his 776 venture fund’s portfolio and commit deeply to the project. “[776’s] founders have a very meaningful ownership stake in the business,” he says. “They’re the ones doing all the work to make it successful. Why should a sports franchise be any different?”

They began to build a group of like-minded investors. Mia Hamm and Julie Foudy, who both played on the team that won the 1999 World Cup, sent an email to former teammates, explaining the mission of the organization. “That email changed my life,” says two-time Olympic Gold medalist Angela Hucles. Now she’s not only an investor but also VP of player development and operations. Other investors include late-night host James Corden, WNBA player Candace Parker, and skier Lindsey Vonn. (The group hasn’t been without some controversy: In March 2021, Angel City asked “Vlog Squad” leader David Dobrik to withdraw his minority stake in the team after one of his crew members was accused of sexual assault. Dobrik stepped down, and the club committed to improving its vetting process.)

Some sports clubs have functioned as vanity projects, or cushy family businesses. That was never the plan with Angel City. In pitching investors, the club’s founders made it clear that they planned to make them money. “We’re trying to create a multibillion-dollar sports franchise,” says Ohanian, “not just a side project that makes us feel good.”

June 23 marks the 50th anniversary of Title IX, the federal law that ushered in a new era for women athletes by removing barriers for women and girls in education and sports. Other barriers have proven more intractable—especially when it comes to professional sports.

It starts with having leagues that are too young to have accrued large fandoms, which is in itself “a function of discrimination,” says Berri. Then there’s the dearth of media coverage, and the lack of both private and public investment. Neither the NWSL nor the WNBA play in any publicly funded arenas that were purpose-built for them. Real growth also requires big broadcasting deals. MLS’s current contracts bring in $90 million annually—and the league is reportedly on the cusp of tripling that amount. The NWSL, meanwhile, gets around $1.5 million per year from CBS, and $1 million from Twitch streams. Additionally, the league has to pay production costs to air its own games.

JULIE UHRMAN, ANGEL CITY COFOUNDER AND PRESIDENTI HAVE THE BEST ATHLETES IN THE WORLD PLAYING A GLOBAL SPORT IN A CITY OF CHAMPIONS.”

Selling this “front of kit” placement is a big deal for any team, says Smith, as it brings in a large amount of annual revenue. The process typically begins with a valuation firm providing estimates of what a team could reasonably charge. The firm that Angel City worked with came back with a valuation of $1 million based on NWSL and WNBA jersey deals. Smith wanted to aim higher: “I was like, ‘What are you talking about? Natalie Portman’s going to be wearing this jersey.’ ” Smith ultimately secured more than $4 million per year in overall jersey revenue, which includes front, back, sleeve, and practice jersey logo placement. Shoe startup Birdies, the sleeve sponsor, signed a four-year deal reportedly worth seven figures. It was Birdies’s first foray into sports partnerships.

Together, these deals add up to the most valuable jersey sponsorship in the history of the league, says Rebecca Hendel, executive director of Endeavor Analytics, a sports and entertainment company that has consulted with Angel City on sponsorship. At the time, it was also larger than at least nine MLS teams’ front-of-jersey deals. “Anytime anything in women’s sports can be bigger than the men’s,” says Hendel, “we’ll take that as a victory.” By the start of Angel City’s first season, Smith and her team had closed 21 revenue-generating partnerships, worth an average of $470,000 apiece.

Leagues of Their Own: A Brief History of Women’s Professional Sports in the United States

One hallmark of every Angel City partnership is that 10% of the sponsorship money is earmarked to go toward the greater L.A. community. DoorDash, for instance, committed to delivering roughly 250,000 free meals to food-insecure Angelenos. Swedish fintech company Klarna—with its first-ever sports sponsorship—promised to create more green spaces in Los Angeles. This unconventional approach to baking social impact into sponsorships has become a defining feature of the club. “It earned the trust of our community and allowed us to get more significant sponsorship dollars,” says Smith, who came up with the idea. Birdies, which was attracted to the team specifically because of this community integration, earmarked its 10% for paid internships for several L.A. high school students, as well as educational scholarships.

Public awareness is growing. Before the start of its first season, the club sold nearly 16,000 season tickets to the Banc of California stadium, which went for between $180 and $51,000 for 10 “Field-level” suites. Premium seats sold out in three days. Angel City also sold more than a million dollars’ worth of merchandise before the team even played its first preseason game.

Angel City’s commitment to increasing opportunity for players is threaded throughout these endeavors. The club created a grant program funded by special merchandise sales for retired players who want to pursue careers in coaching, refereeing, sports media, or the front office of teams. “We wanted to give them a pathway to invest in and get back to the sport,” Uhrman explains. She’s also exploring ways to compensate current players who tap into their social followings to sell tickets. (Logistics are still being worked out with the league.)

The club is mindful of creating a team culture that addresses the issues that have plagued women’s soccer. During the draft, head coach Freya Coombe looked for athletes who were interested in putting down roots in L.A., and kept the roster small, so the new team could jell and players wouldn’t have to stress about being traded. The club looked for other ways to improve player safety. Hucles says that they purchased phones “issued by Angel City, property of Angel City,” for staff to communicate with players, in the hope that it will act as a deterrent for any inappropriate communications. “The first thing we put into place was a code of conduct, reporting mechanisms, and HR,” says Portman.

Leagues of Their Own, continued

National team member Christen Press, who previously played professionally for the English Women’s Super League, was the first player to sign a contract with Angel City, reportedly for slightly more than $700,000 for three seasons, making her one of the highest-paid athletes in the history of the NWSL. (Teams are able to pay above the league’s maximum salary by using an additional allowance called “allocation money.”) “When you’re part of a new franchise, there’s a responsibility to establish culture and standards,” Press says. She’s looking to the team to “push the needle toward a truly professional environment where the players are valued and the fans are valued in a way that they aren’t anywhere else in the world.”

Angel City’s first matchup, a preseason game in March against the league’s other new expansion team, the San Diego Wave, ended in a tie. But the game, held in the 10,000-seat Titan Stadium at Cal State Fullerton, was successful in other ways. At the start of the game, Portman flipped the coin in the center of the pitch, alongside her husband and their two kids. Wearing black Angel City jerseys and the team’s black and pink scarves, fans—Ohanian and his daughter among them—cheered and beat drums. Players couldn’t hear one another over the crowd. When Savannah McCaskill scored the team’s first-ever goal, the stands erupted.

As competitive as the team is, Angel City’s leaders are focused on sharing what they’re doing with other clubs in the league. “The mindset of Julie and the team is very much to open-source the best practices,” says Ohanian. “We need to improve the economics of all the clubs.”

Other teams are already copying the celebrity-investment model. Naomi Osaka invested in the North Carolina Courage in January 2021; the Washington Spirit now counts Chelsea Clinton and Jenna Bush Hager among its owners. “It’s great for the sport and the league overall to have more investors [who can provide] more visibility,” Hendel says.

Leagues of Their Own, continued

Angie Long, co-owner of the Kansas City Current NWSL team, is a former classmate of Nortman’s from Princeton and chief investment officer at Palmer Square Capital Management, which manages more than $22.1 billion in assets. She spoke with Nortman after the 2019 World Cup about what it takes to buy a team and bring it to market and—with her husband, Chris, and fitness entrepreneur Brittany Matthews—she launched a club in Kansas City, Kansas. (The city’s previous one folded in 2017.) The Current, now in its second season, has adopted Angel City’s 10% community sponsorship model. “We absolutely thought it was a phenomenal idea, a way to tie together sport and the community,” Long says. Last fall, she and her co-owners announced plans to build a $90 million, 11,500-seat NWSL stadium along the Missouri River waterfront.

There are signs that the league is hitting its stride. In 2021, media mentions and impressions for the league grew 334% from 2020, according to sports consultancy Navigate. In February, 19-year-old Trinity Rodman, 2021 Rookie of the League, signed the biggest contract in the history of the NWSL. The four-year extension with the Washington Spirit was reportedly worth $1.1 million. Last November, a record 525,000 viewers tuned in to watch the NWSL final, a 216% increase over the 2019 final. And this April, a preseason matchup between Angel City and the San Diego Wave notched 456,000 viewers on CBS. “That’s a lot of people watching women’s soccer,” said Uhrman over Twitter.

Even so, only five of the league’s 146 matches in the 2021 season were broadcast on CBS. The rest were available on its streaming service, Paramount Plus, and the cable CBS Sports Network, along with Twitch. But the league’s streaming rights for Twitch are up in 2023, and CBS’s deal expires in 2024, meaning more lucrative arrangements could be coming.

Burke of the NWSL Players Association helped negotiate the league’s first collective-bargaining agreement in January. She says part of the reason the players signed a longer-term, five-year contract was the stipulation that they will receive 10% of the net broadcast revenue if the league is profitable in years three, four, and five of the CBA. “We talked a lot about wanting to bet on ourselves and being willing to take risks because we believe that there is tremendous growth opportunity,” she says.

That’s Angel City’s position, too. Ohanian, for one, is confident. When he gets hate tweets about how he’s wasting his time investing in women’s sports, he saves them in a special Dropbox folder. “They give me energy,” he says. “Every time I get another investor update about Angel City or see some more progress, I just think back to those tweets, and I get even more motivated.”

Tomorrow night, LA's new professional women's soccer team, Angel City FC, will take the field at Banc of California Stadium for its season opener. The team was cofounded by actor Natalie Portman, venture capitalist Kara Nortman, and entrepreneur Julie Uhrman, alongside lead investor Alexis Ohanian, and a who's who of soccer legends, including Abby Wambach, Julie Foudy, and Mia Hamm. So it's no surprise that expectations for the team are high. “We love soccer,” says Portman. “But we also have a secondary mission, which is to push forward the state of conditions for female athletes.” There's a lot of work to be done in a league where the salary minimum is just $35,000 and the maximum is $75,000—and where male head coaches at five of 10 teams were fired or resigned in 2021 due to claims of misconduct. I took a look at

Tomorrow night, LA's new professional women's soccer team, Angel City FC, will take the field at Banc of California Stadium for its season opener. The team was cofounded by actor Natalie Portman, venture capitalist Kara Nortman, and entrepreneur Julie Uhrman, alongside lead investor Alexis Ohanian, and a who's who of soccer legends, including Abby Wambach, Julie Foudy, and Mia Hamm. So it's no surprise that expectations for the team are high. “We love soccer,” says Portman. “But we also have a secondary mission, which is to push forward the state of conditions for female athletes.” There's a lot of work to be done in a league where the salary minimum is just $35,000 and the maximum is $75,000—and where male head coaches at five of 10 teams were fired or resigned in 2021 due to claims of misconduct. I took a look at

![1972: Title IX prohibits sex-based discrimination in schools and educational programs, including sports that receive federal funding. At the time, there are just over 300,000 women and girls playing college and high school sports in the U.S. [Illustration: Goran Factory]](https://images.fastcompany.net/image/upload/w_562)

No comments:

Post a Comment