The Beauty of Looking at Beauty

Science tells us that gazing upon beautiful things is a form of self-care. Can it also be making us more beautiful?

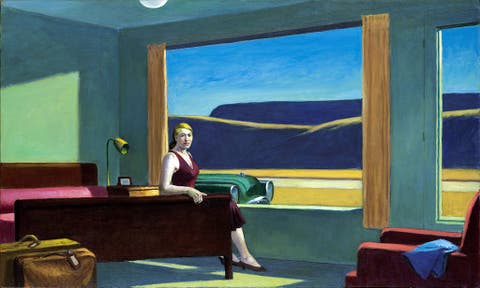

The ubiquitous Calgon commercials from the 1980s all followed the same formula: Exasperated woman rattles off her woes (The boss! The baby!) before crying out, “Calgon, take me away!” and being immediately transported to the blissful solitude of a bubbly bathtub. Over the course of this past year, my version of that Calgon bath wasn’t a bath at all but looking at art; scrolling through a museum’s neatly archived online collections teleported me to a similarly euphoric place. The soothing palettes of Etel Adnan; Jacqueline Marval’s pastoral scenes of women lounging around in beautiful frocks; Edward Hopper’s lovely depictions of solitude; and countless images of New York—especially photos chronicling its nightlife and street life by Meryl Meisler and Robert Herman—to remind me of my home’s pre-pandemic spirit.

That looking came before language, a point art critic John Berger established in the first lines of 1972’s Ways of Seeing, is an indication perhaps of its far-reaching power. “If you look at something for a long period of time and try to understand it, you get a deeper pleasure,” says Ellen Winner, professor emerita of psychology at Boston College and author of How Art Works. She often has her students engage in “slow looking” exercises, spending up to an hour with a particular work, which is a challenge in this age of speed-scrolling.

But even a few moments of looking has benefits. “Slowing down to contemplate a piece of artwork can provide solace and balance, something sorely lacking for many of us, even in normal times,” says Sam Ramos, associate director of innovation and creativity at the Art Institute of Chicago. That act of looking is also an act of destressing. And for those who have struggled to connect with the mindfulness methods extolled by wellness gurus, art can serve as its own form of meditation. “Rather than just being a distraction from what’s happening, you find yourself being 100 percent present,” says Marie Clapot, an associate educator at the Met. “Looking at art is very much a self-care tool.” Doctors in Canada in 2018 were so convinced of art’s serotonin-boosting abilities that they began to hand out prescriptions for museum visits to their patients; a trip to the museum was considered a boon to the healing process.

Art doesn’t simply have the ability to make you feel good, it may also help you look good. Research has shown that those regularly exposed to art have experienced dramatic dips in cortisol, the increased production of which can affect not only mental well-being but also sleep and digestion, and accelerate the aging process of the skin. While lowering cortisol is key for curbing waves (or, when it comes to this past year, tsunamis) of anxiety, it’s also essential for diminishing the damaging impact of stress on the skin, a precursor to inflammation and a slew of conditions like acne and eczema.

Since physical trips to a museum posed a challenge this year, many institutions pivoted to amplifying their digital accessibility—and it turns out you don’t need to be in the same room as an artwork to feel its power. Coming together and sharing the experience of art (even an action as simple as posting a picture on Instagram) has, Ramos says, the power to make us feel comforted, stronger, and more connected. It can also be a catalyst for critical thinking. At the Art Institute of Chicago, Ramos leads civic wellness workshops for medical students and professionals. “Artwork is a starting point for conversations about power, race, and empathy,” he adds.

Another point Berger makes in his landmark book is that art is relational: The perspective everyone brings to the viewing of a piece influences individual reactions to it. Beautiful art, and beauty too, for that matter, is subjective; a painting you may find beautiful doesn’t necessarily have a universal appeal. “What art can do is make us aware of the beauty that exists elsewhere,” Ramos says.

Both physically and psychologically. “Beautiful art makes you step away from yourself and this everyday world so you can think bigger,” says Dina Schapiro, assistant chair and director of the graduate creative arts therapy program at the Pratt Institute. It also allows you the space to dream, a feeling you get even when the thing of beauty you’re gazing at is an actual beauty product: Hermès’s lacquered, color-block lipsticks, Byredo’s rainbow of shiny, platinum-encased Colour Sticks, or an exquisite handblown bottle of Perfumer H’s concoctions always manage to transport me to a happy place.

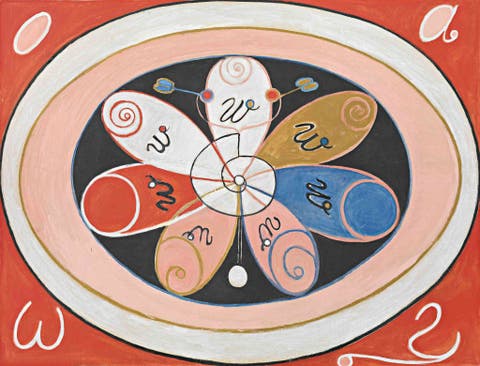

In looking back at the images I saved this year, I noticed that one shape kept recurring: the circle. There it was in paintings by Jordan Belson and Hilma af Klint, Alma Thomas and Carla Prina. “We collectively relate to circles, and they’re the first shapes we see when we come into the world,” Schapiro says of their appeal.

Agnes Pelton, another artist whose circles I kept returning to, was intentional in her use of them. In her mystical paintings they conveyed calm radiance at the center of a storm. Consider the magnificent Nebra Sky Disk; a round bronze plate dating back to the Iron Age, it’s one of the earliest depictions of cosmic phenomena. The epitome of calm radiance, it is indeed deeply soothing and pleasure-inducing to look at, and reassuring, too—a reminder that beauty exists elsewhere but also that it endures. This circle has withstood, and so will we.

This story appears in the May 2021 issue of Town & Country.

No comments:

Post a Comment