Art Market

Why Some Artists Turn Away Would-Be Buyers

Most creative people have little control over who enjoys—or doesn’t enjoy—their work. Dancers, musicians, and Broadway actors open their performances to anyone who can purchase a ticket. Cinemas sell seats until the theater fills. Bookstores place no restrictions on who can buy books. The barrier to access is often economic. If you can pay the price of admission, you can experience the art.

Visual art, however, works differently. Galleries typically sell one sculpture, painting, photograph, video, or limited edition of those media at a time to private collectors and institutions. This structure has encouraged some artists to be more scrupulous about their sales. To own their art, collectors must meet certain criteria related to their ideologies, financial backgrounds, reputations, and plans for exhibiting the artists’ work. Though placing art is traditionally a gallery’s job, a number of artists take steps to exert greater control over their own legacies.

painter

may be the most famous art-historical example of this practice: He refused to work with a gallery, keeping thousands of canvases and handling most sales himself.

One of the most common ways for artists to influence their markets is by privileging direct sales to museum collections and to private collectors with close institutional ties. While many galleries prioritize such sales anyway, some artists are more adamant about this desire.

Institutional priority

, who shows with Vielmetter Los Angeles and London’s Stephen Friedman Gallery, is candid about her wishes. She directs her galleries to sell to museums, she said, so that “someone who looks like me can be inspired by my work and think, ‘I could do this too.’” As an African American woman who grew up in a lower socioeconomic bracket, museums were one of the few places she could see herself reflected in American culture. In these public spaces, she found models for how to paint.

Sometimes, Roberts told me, a gallery will come to her with an offer from “an amazing collector.” They’ll tell her which artists are already represented in the collection and share why it’s important to have work there, too. “I have relented,” she admitted. Yet she’s also getting more vocal. Now, if the gallery doesn’t make an offer that’s suitable to her, Roberts will simply ask for the artwork back. She’d rather have her art than the funds.

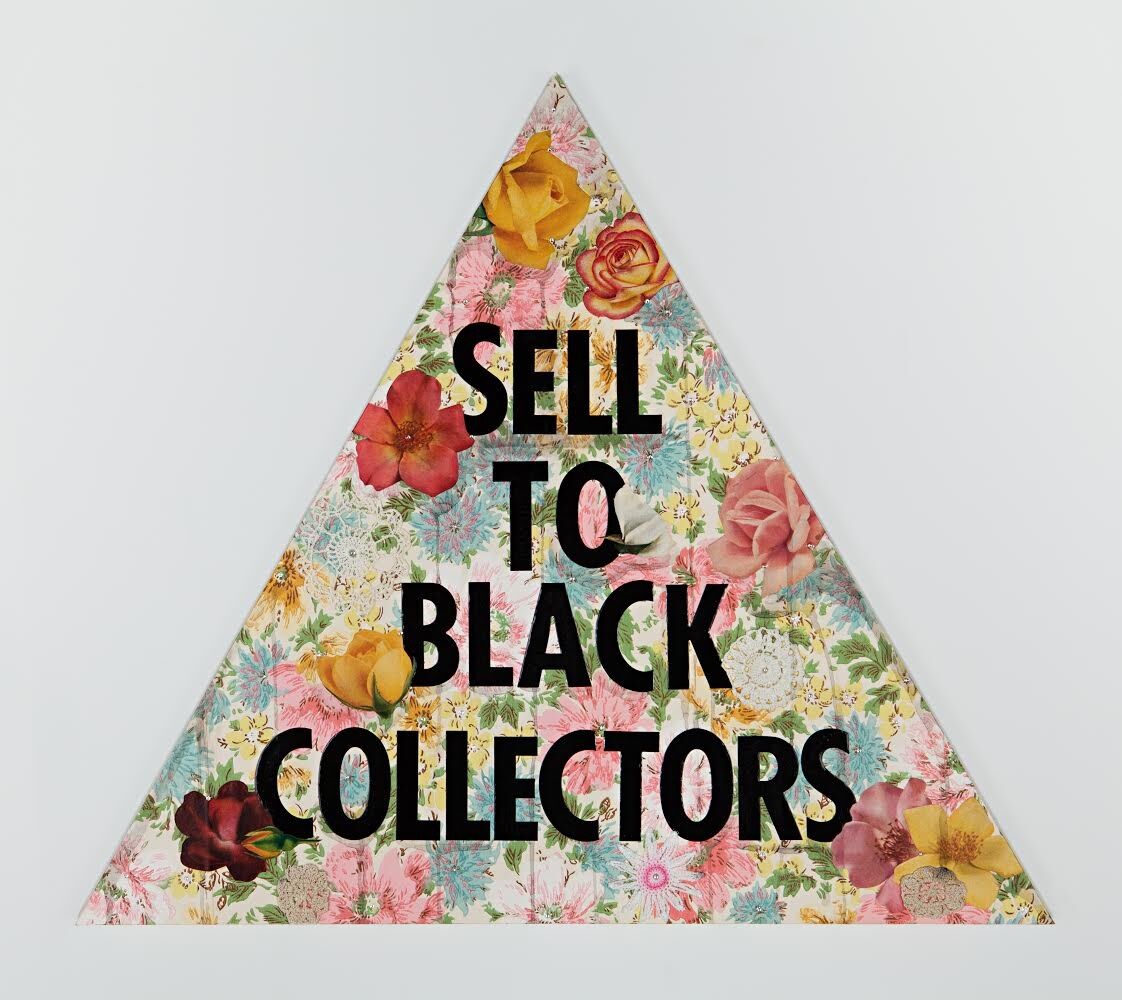

Genevieve Gaignard, Sell To Black Collectors (Pink), 2020. © Genevieve Gaignard. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles.

A few years ago, Roberts made a series of mixed-media paintings about George Stinney Jr., a 14-year-old African American boy who was wrongfully convicted of murdering two white girls and executed in the early 1940s. Roberts wanted all these works in public collections. “Three ended up in private collections, which I’m still salty about,” she said. “A lot went to public collections where people can learn his story, which I’m happy about.”

Connecting with collectors who care

Artists’ motivations, when they specify that they want their works to go to museums, can be more economic than ideological. “Most Lower East Side dealers do their best to select people who will care for the work and who don’t treat it like a commodity,” said Jasmin Tsou, owner and director of the gallery JTT. In other words, selling to private collectors always creates a risk that many young artists want to avoid: seeing their work turn up at auction.

That said, some artists see significant value in selling to a diverse group of private collectors.

noted that she has started advocating “access for collectors of color.” Black artists and their works are being celebrated right now, and, she said, “it’s fitting that the work would be able to live amongst at least some of the folks it’s representing.”

Gaignard echoed Roberts in saying that, for so long, people of color couldn’t see themselves “represented in visual stories of America and beyond.” She believes that when there’s high demand for an artist’s work, “it’s important for collectors of color to be given early access to previews and first rights to purchase,” she said. “So often, they are left off these lists.”

Artists whose works are in high demand may also have requirements about specific sales.

, for example, reportedly mandated that all four works in her presentation at Hauser & Wirth’s booth at Frieze Los Angeles go to institutions. This didn’t mean that a museum’s acquisitions committee had to buy them. Private collectors can purchase artworks that they promise to certain institutions—often with the hope of getting to acquire a work for themselves later.

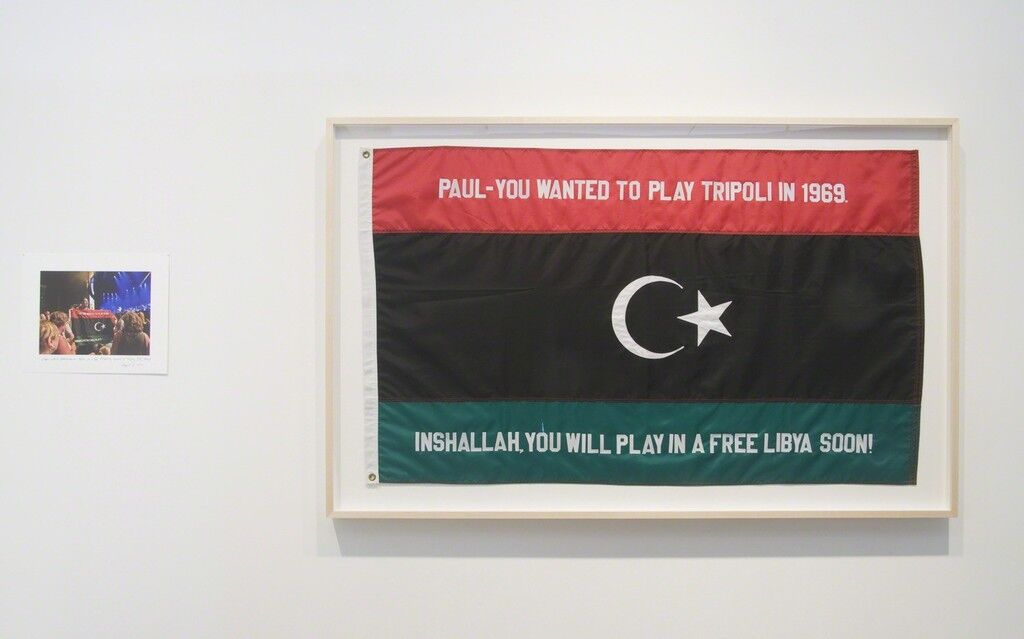

The conceptual artist

may be the most famous contemporary exemplar of artists’ fraught relationships with private collectors. She’s worked on and off with galleries for years, selling (and not selling) work that critiques both art museums and the market, like her extensive catalog of U.S. museum trustees’ political donations during the 2016 presidential election. Her infamous 2003 work Untitled involved sleeping with a collector who “bought” the piece, which comprised the evening itself and a video of the event.

Seal of approval

Some artists are even more specific about who can and can’t purchase their works.

, for example, is part of the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition, which advocates for the rights of migrant workers building institutions on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island, including a new branch of the Guggenheim. Rakowitz is cautious about selling work to any institution targeted by Gulf Labor’s boycott, or individuals affiliated with them. Yet according to his dealer, Jane Lombard, that’s not an issue on her end. Her gallery has been fortunate, she said, “because his political views are well known.” If you’re looking to buy a Rakowitz work, you’re probably aware of his restrictions.

Lombard said that in her experience, artists will make specifications regarding who can collect their works “based on their personal grievance, political views, and the causes for which they are passionate.” She believes it’s “becoming more common for artists to have issues with institutions,” she said. On the other hand, Scott Briscoe, manager at Sikkema Jenkins & Co., said that while there have been exceptions, most of his artists don’t “ask to be consulted as to whom buys their work.” He would not reveal what those exceptions were.

Making collectors commit

Sometimes, an artist’s requirements are simply aesthetic.

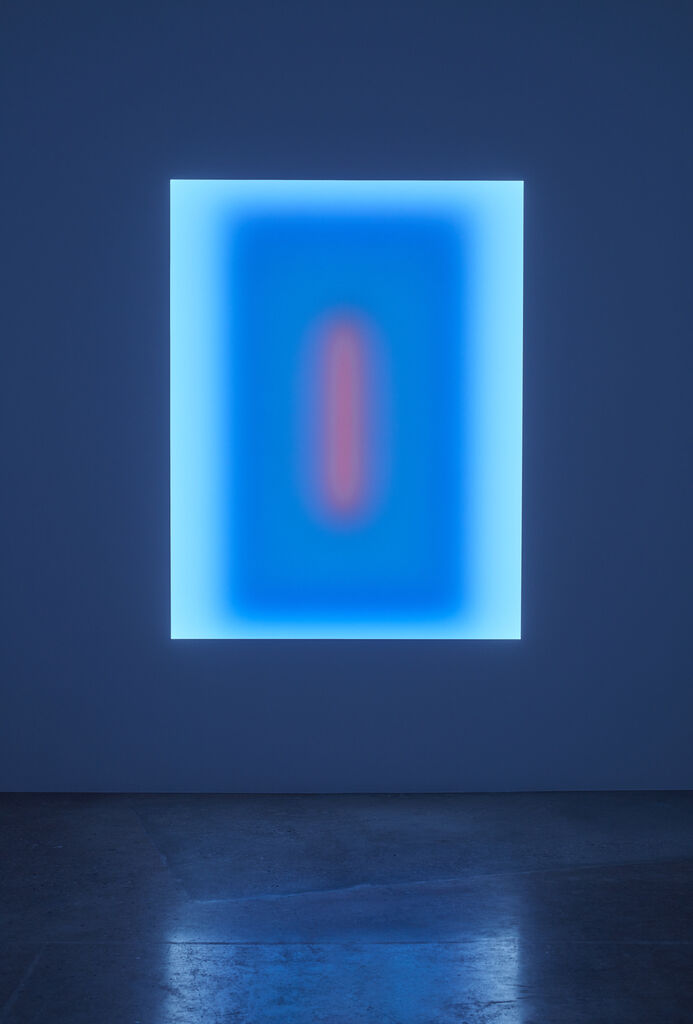

’s monumental light works, for example, have very specific logistical requirements. “Everyone loves the ‘Glass’ works, but only a handful of collectors are willing to commit to the architectural buildouts required to install these works,” said Beatrice Shen, director of sales at

, referring to the artist’s series of installations featuring cutaways lined with LEDs that gradually shift colors. To install a “Glass” work, an owner must create a kind of window within a wall, to hold the light and color. “The collectors need to be visionaries,” Shen said.

Turrell’s “Skyspaces” require even more exacting architectural parameters. Collectors must have—or build—specifically proportioned chambers. They must be able to carve an aperture in the ceiling to “frame the open sky,” according to Andrew Black, the gallery’s director of communications.

At the far end of the spectrum is

, who prohibits anyone from buying their work at all. Instead, institutions and individuals may rent them. To take a Rowland work home, or back to the museum, interested parties must sign a contract. This process forces the buyer to recognize Rowland as a producer of property with their own rights—a privilege not always afforded to artists.

Selling an artwork, unlike selling a book or a ticket to a movie, requires artists to part with something dear to them, which they may never see again. But to sustain their livelihoods, and to generate any recognition for their work, they have to keep putting themselves through this difficult process again and again. Given the physical and emotional work they put into their practices, it’s not surprising that some artists want to have a say in where the fruits of their labor end up.

Alina Cohen is a Staff Writer at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment