Creativity

In a Countryside Residency in the South of France, Artists Escape from City Life

Courtesy of Moly-Sabata.

It’s a summer evening in the South of France, on a small island in the middle of the Rhône River. A group of artists gathers for an apéritif on a sun-warmed patio, bordered by flowering vines. The conversation turns from today’s grocery haul, picked up at the farm next door, to a sculpture pulled from the kiln earlier that day.

This is how most nights at Moly-Sabata, France’s oldest active artist residency, transpire. A drink among artists and friends leads to dinner, served en plein air, and hours of casual conversation, about art, life, or the perfect baguettes being turned out by the baker down the road.

Since its founding by artist-couple

and Juliette Roche in 1927, Moly-Sabata has been a sanctuary for artists working in all mediums, and a space that values camaraderie as much it does the creative genius of each individual resident.

This year, it celebrates its 90th birthday—nine decades of bringing artists together within the age-old stone walls of a property that more than one resident has remembered, lovingly, as “magical.”

Moly-Sabata's first artists, Australian potter Anna Dangar and French composer Cesar Geoffray, pictured with Geoffray's family, ca. 1930. Courtesy of Moly-Sabata.

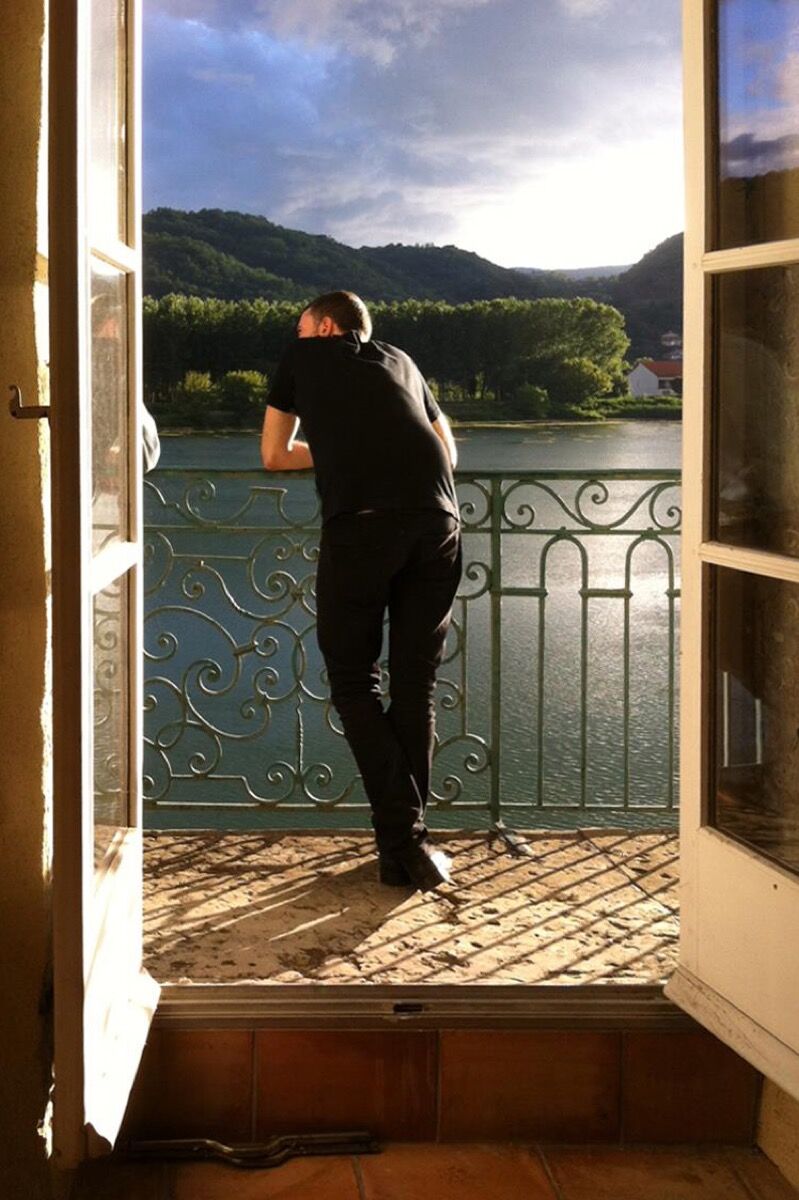

Artist Jean-Baptiste Bernardet at the balcony of his studio at Moly-Sabata, July 2014. Courtesy of Moly-Sabata.

“When you’re on the premises, it really feels like a whole world unto itself,” explains artist

, who first landed at Moly-Sabata in 2014 and has returned twice since. “It’s a really special place that’s conducive to working, not only because of its location and the resources it provides, but also because of how it’s run: as an inclusive environment where artists create together; where they share a curiosity about art, the world, and each other.”

In the late 1920s, when Gleizes hatched his plan for Moly-Sabata, he envisioned a retreat where his “peers could escape the metropolis and embrace a way of life more connected to the earth,” explains Joël Riff, Moly-Sabata’s curator and communications director. Gleizes, a pioneer of the

movement, had been rubbing elbows with the likes of

in Paris.

But he craved a more serene environment, where he and fellow artists could create and converse away from a litany of stresses that, in his view, were byproducts of urban life and industry. He believed that the spirituality essential for artistic creation had been stamped out by materialism—but that it could be rekindled by a return to nature and traditional art forms. So, on a property he and Roche purchased not far from her childhood home, they built Moly-Sabata, as an artist commune and teaching center.

Moly-Sabata to the river Rhône. Courtesy of Moly-Sabata.

Moly-Sabata hasn’t changed much since Gleizes and Roche first invited their artist friends and students to the property, early in the 20th century. It remains the tranquil environment that the couple set out to create.

“No bills, no invoices, no social meetings, no openings, no shopping distraction, no boyfriend waiting at home for his meal to be cooked, just work, work, work, work, work, reading, and lots of naps,” explains painter

, who spent summer 2014 at the residency. “Time is elastic, and if your bed is not far from your studio, you just work five times more than when there’s the outside world.”

The nucleus of the property still exists, too: an 18th-century mansion, complete with a sprawling balcony and windows decorated with sea-green shutters that look out over the Rhône. Five studios surround it, where visiting artists live and work. One, which Halvorson settled into for the summer of 2014, operated as the poterie, or pottery studio, during Gleizes’s time. It was there that one Cubism’s few female artists, the Australian expat Anne Dangar, made her famed ceramics and taught pottery lessons to the surrounding community.

When Halvorson entered the space, it had been untouched for several decades. “It was the history of the pottery studio, of Moly-Sabata, and of the Rhône that appealed to me—and that ended up informing new work,” she says. Vestiges of the studio’s past—a clay-caked leather apron and long-forgotten tools tucked away in a massive armoire—cropped up in paintings she made while there.

The property and the people Halvorson encountered beyond the studio walls influenced her practice, too. She took her sketchbook to the banks of the Rhône or the meadows dotting Moly-Sabata. She discussed her work, and the work of others, over communal dinners with fellow residents, friends, and the Moly-Sabata staff, including Riff, director Pierre David, and administrator Virginie Retornaz.

Photo by @joelriff, via Instagram.

The Rhone room. Photo by @joelriff, via Instagram.

It’s these long group gatherings, and the conversations that emerged from them, that are most vivid in Halvorson’s memory when she thinks about her residency. “There’s just such robust conversation and sense of community there. As an international resident, I felt so welcomed,” she remembers. “Having conversations about art outside of America, as an American, has been really significant for me, and a lot of that happened in the gardens during our communal dinners.”

As the residency celebrates its 90th birthday this year, it not only celebrates its history, but also its perennial capacity to inspire creativity. “With its history and cultural significance, Moly-Sabata could be in danger of becoming kind of museum-ified,” says Halvorson. “But it never feels like that. It feels like a place for real creation to happen.”

Alexxa Gotthardt is a contributing writer for Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment