dec2018/jan2019 » » SERRA DE MONTEMURO » » Portugal

plenty of sheep and one cow... above Ferreiros de Tendais

...|...

view from Ferreiros

...|...

the dog... the sign

...|...

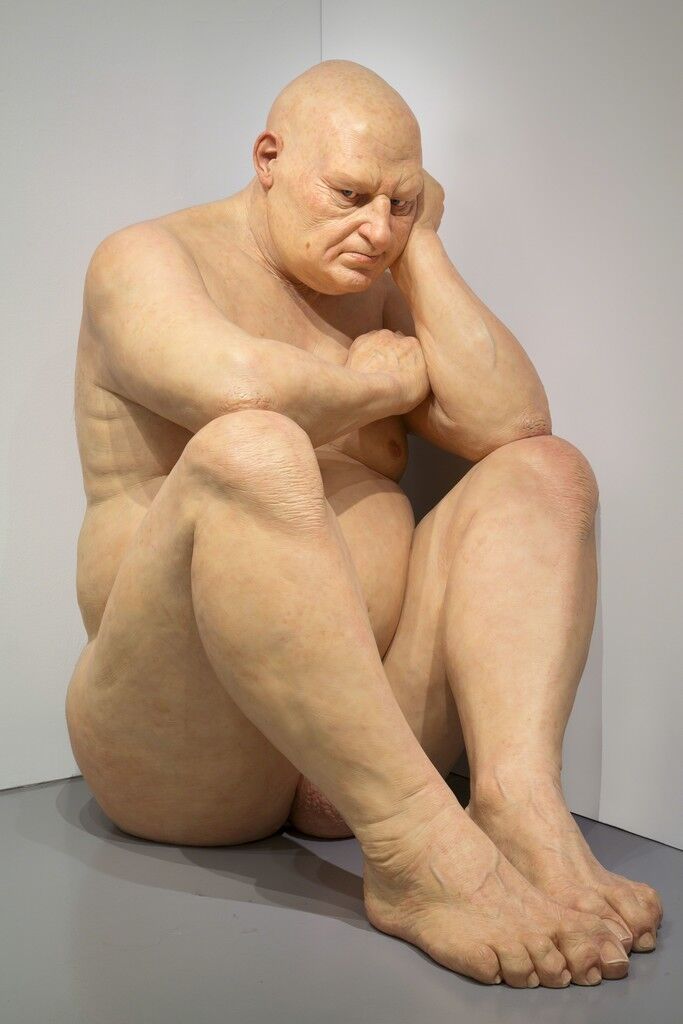

the dark side... of the mmm

...|...

...|...

...|...

the dog... the sign

...|...

the dark side... of the mmm

...|...

feb.2019... snow time

... and now this amateur is slippin' and slidin' and blocked the road for the rest of us...(that means me)

...|...