Art World

From the Met and Christie’s to Cheim & Read: How the Art World Guest Stars in ‘Ocean’s 8’

The industry makes more than just a cameo in the summer blockbuster.

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art plays a starring role in one of this year’s most anticipated summer movies, Ocean’s 8, the all-female update to the beloved Ocean’s trilogy starring George Clooney and Brad Pitt. With their eyes on a gigantic diamond necklace that has been locked away in the Cartier vault for half a century, a sophisticated band of women thieves infiltrates the Met Gala, attempting to pull off an audacious heist dressed in their best black tie gowns.

Hitting theaters on Friday, 11 years to the day of the release of the last film in the series, Ocean’s 8 stars Sandra Bullock as Debbie Ocean, sister to Clooney’s Danny Ocean. She’s spent over five years in jail with nothing to do but to plan the perfect crime, targeting a leading cultural institution during the world’s most exclusive party. Her crack team includes nightclub owner Lou (Cate Blanchett), jeweler Amita (Mindy Kaling), and thief-turned-suburban mom Tammy (Sarah Paulson).

The Met Gala in Ocean’s 8. Photo courtesy of Barry Wetcher, ©2018 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Ocean doesn’t want to rob the Met exactly: The target is a $150 million vintage Cartier necklace that has been loaned to actress and Met ball hostess Daphne Kluger (Anne Hathaway) for the occasion, thanks to some behind-the-scenes machinations by Ocean and her team.

The planned robbery may center around a necklace, but the filmmakers paid close attention to every detail about the museum and its famed gala, which celebrates the Costume Institute and its annual spring show. In Ocean’s 8, that’s “The Scepter and the Orb: Five Centuries of Royal Dress.” At the suggestion of Anna Wintour, the film tapped Hamish Bowles, Vogue’s international editor-at-large, who has curated real-life fashion exhibitions, to create a convincing facsimile of one for the movie.

Cartier vault created for Ocean’s 8. Photo courtesy of Barry Wetcher, ©2018 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

“Rather than getting into the idea of doing period costume, we framed the exhibition around the idea of royal dress, and its enduring influence on fashion designers,” Bowles said in a statement.

(In real life, this year’s exhibition was the Catholicism-inspired “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination;” and the gala saw several Ocean’s 8 stars walk the red carpet, including Rihanna dressed as a sexy pope with a Cartier necklace.)

Rihanna at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” Costume Institute Gala. Photo by Sean Zanni, ©Patrick McMullan.

It took Bowles and production designer Alex DiGerlando nine months to plan, design, and bring “The Scepter and the Orb” to life. (If you’re wondering what corner of the Met managed to hide an entire fake show, they didn’t: The set was built at Gold Coast Studios on Long Island due to time and space constraints.) The elaborate set-up displayed the garments over a striking reflecting pool—although some of the water was added digitally to protect the clothes from moisture and humidity.

Bowles secured loans of gowns from Alexander McQueen, Valentino, Dolce & Gabbana, Zac Posen—who have cameos in the film—and other top-name designers, all inspired by the royal fashions of the courts of the Tudors in Great Britain and Louis XIV of France. The costumes were mounted and installed by professional museum conservators, and paired with custom-made crown jewels, handcrafted by the film’s prop master, Michael Jortner, in collaboration with a jeweler.

To complete the illusion, Bowles also wrote real wall text and labels identifying each piece and its historical references, even though that level of detail was never going to appear on screen. “Everything we did was absolutely as we would have done for a legitimate museum show,” he said.

Sandra Bullock as Debbie Ocean, Cate Blanchett as Lou, Mindy Kaling as Amita, Sarah Paulson as Tammy, Awkwafina as Constance, Anne Hathaway as Daphne Kluger, Rihanna as Nine Ball and Helena Bonham Carter as Rose in Warner Bros. Pictures’ and Village Roadshow Pictures’ Ocean’s 8. Film still courtesy of Barry Wetcher ©2018 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

The movie also gives the Met’s real art collection some time in the spotlight. As Ocean and her squad case the joint, shots linger lovingly on real-life masterpieces by greats such as Vincent van Gogh, Amedeo Modigliani, Paul Cezanne, and John Singer Sargent.

“I called ‘safety’ meetings for the art, as we would for a major stunt. I mean, literally, one false move and you’ve wrecked more than the budget of the movie,” director Gary Ross said in a statement. “So we had to be very, very careful. We had extensive meetings with the Met about what we were going to do, letting them know every single movement: how we would load in and out, where the cameras could be and where they couldn’t.”

Sandra Bullock and Cate Blanchett in front of the Met, in Oceans 8 (2018). Screenshot via YouTube.

Thankfully, the filming went off without a hitch. It was a 10-day shoot, the longest the Met has ever allowed, which was a unique experience for the cast and crew. “In-between shots, you could walk around and take in the museum in a way you’d never taken it in before—just stop and look at a piece of art, inspect it, and observe the brushstrokes,” said Bullock in a statement. “We had two weeks to just savor everything, so shooting at the Met was a gift on many levels.”

At one point, Ocean stands before Emmanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware. Suddenly, there is a commotion—but not because a famous painting has been stolen. There, next to the monumental original, is a smaller version of the painting, but with each male figure replaced—in a meta nod to the film’s casting—with a woman.

The prelude to the “Met Gala” as seen in the trailer for Oceans 8 (2018). Screenshot via YouTube.

Thanks, presumably, to a bogus tip from Ocean, the story gets picked up in the press, leading to headlines in an online art magazine claiming that British street artist Banksy, known for his guerrilla artworks, is behind the clever prank. (For the record, artnet News would not report a new “Banksy” as fact unless the piece was claimed by the artist on his website.)

The ersatz Banksy, however, is just a distraction from Ocean’s real objective. She wants the Met to review their security protocols, which will give her team a chance to hack the system in preparation for the robbery.

Banksy, of course, did manage to sneak a work of his own into the Met back in 2005, surreptitiously hanging what the New York Times described as “a small, gold-framed portrait of a woman wearing a gas mask” in the American wing of the museum. He did the same with other paintings at the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the American Museum of Natural History.

Banksy hanging a painting of a woman in a gas mask at the Met in 2005. Photo courtesy of Banksy.

The Met, of course, isn’t the only facet of the New York art world on display in the film. Once released from prison, Ocean heads straight to a swanky gallery opening. She’s there to see art dealer Claude Becker (Richard Armitage), her ex-boyfriend, owner of an eponymous space at 547 West 25th Street.

Seasoned gallery-goers will recognize that address as that of Cheim & Read. The scene was shot at the space last winter, during the exhibition “Tal R: Keyhole.” Filming took place after hours, allowing the gallery to remain open as usual during the day.

“We were pleased to host the crew during the shoot,” said the gallery in a statement. “We look forward to seeing how the film turns out.”

Art-world cognoscenti will also spot auction house Christie’s, which becomes “Yardley’s” in the film, where Ocean is improbably able to trade her ill-gotten diamonds for cold hard cash. She enlists a slew of innocent looking old ladies to spin a yarn about receiving the diamonds as gifts from lovers when they were young.

Photo courtesy of Eric Bidou/Cartier.

In real life, selling stolen diamonds is about as easy as moving a famous painting—aka impossible. “You’d be lucky to get 10¢ on the dollar,” former diamond wholesaler Howard Rothauser, the founder of the jewelry website Dacarli, told Bloomberg. “It would be unsalable as a necklace,” not least of all because valuable diamonds are typically laser-etched with a Gemological Institute of America Inc. registry number.

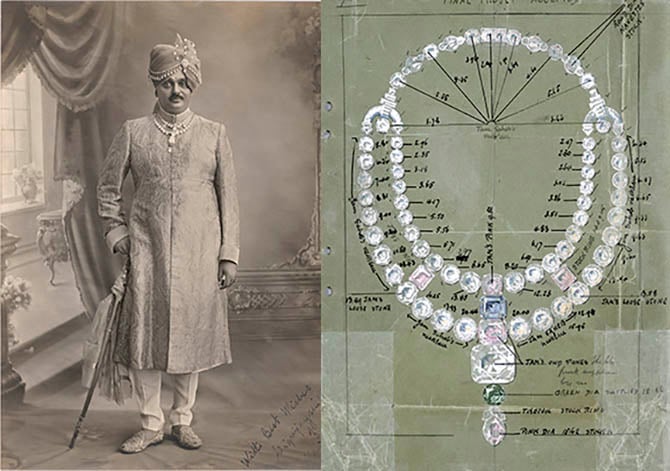

As for the film’s Toussaint necklace, it is a fiction—albeit one based on a historical Cartier piece, designed in 1931 for the Maharaja of Nawanagar by Jacques Cartier. The centerpiece of the necklace, which no longer exists, was the Queen of Holland, a blue-white diamond weighing 136.25 carats. Cartier drew on archival photographs and sketches to create a new version of the necklace at their Paris high jewelry workshop, scaled down by about 20 percent to fit Hathaway’s petite frame.

“The Toussaint necklace went through the exact process as a usual piece,” said Pierre Rainero, image, style, and heritage director for Maison Cartier, in a statement. “Normally, for a special order of such importance, the minimum would be eight months. We actually made this necklace in eight weeks.”

The necklace is named in tribute to 1930s-era Cartier creative director Jeanne Toussaint who helped create the brand’s well-known panther designs.

The Maharajah of Nawanagar wearing the necklace by Cartier-London in the drawing at right that inspired the necklace in ‘Ocean’s 8’.

Photo Cartier Archives London © Cartier

Photo Cartier Archives London © Cartier

Had Cartier created a piece with real gemstones, it would have been worth over $100 million. To put that into perspective, the film’s budget was only $70 million. Instead of diamonds, the fictional piece is made from zirconium oxides in a white gold setting, although many real necklaces from the jeweler appear in scenes shot at the Cartier mansion, which was outfitted with a massive vault set during filming. (To pull off the heist, Ocean 3-D prints a cubic zirconium copy.)

Both as a film prop, and a plot device, the Toussaint is a success, setting the wheels in motion for a delightful, crime-filled romp through the New York art world. As a summer blockbuster loaded with female star power that swaps the casinos of Vegas for the hallowed halls of the Met, Ocean’s 8more than delivers on its promise, with smart, savvy protagonists that seem prepared for any obstacle that comes their way, with a behind-the-scenes look at the Met Gala as a bonus!

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Article topics

No comments:

Post a Comment