Art Market

How Starving Artists Could Benefit from Smarter Contracts

The art world has a late payment problem, and the people who suffer from it most are artists. According to UBS and Art Basel’s The Art Market | 2018, dealers report that it takes an average of two months to complete payment for a work, and, from personal experience working at art galleries, we know it often takes longer.

In most other industries, this would be unacceptable, but the art industry is different. Dealers have to protect their relationships with collectors, even if the collector is stiffing the artists. Fortunately, there’s a solution: smart contracts, which are contracts based on computer algorithms that not only deliver the contract terms, but also execute the purpose of the contract within its terms.

In an ideal world, the following scenario would be true: An artist has a show with a gallery, consigning works for the show to the gallery at a 50/50 split. The gallery exhibits the work and sells it to collectors, or, optionally, through a consultant. The collector pays the gallery within 30 days of the sale, after which the gallery immediately pays the artist his or her half.

Unfortunately, the scenario often looks more like this: The collector (often the wealthiest person in the transaction) who bought the consigned work from the gallery does not pay right away, or pays in installments, or cancels the sale long after agreeing to pay. If indeed the money arrives, the gallery might not pay the artist her share, or even inform her right away. Instead, the gallery may use the funds to pay off other artists who have been waiting even longer for their money, or to cover its upcoming booth at an art fair, or any number of other expenses.

In essence, money owed to artists can become a gallery’s credit line. With dealers such as Perry Rubenstein or Ace Gallery, this can carry on for years or even decades before coming home to roost. Sadly, because of the difficulty dealers face in accessing credit or small-business loans, this is hardly a rare phenomenon, even among the most ethical of dealers.

In extreme examples of delayed or absent payment, an artist may even be forced to press legal action. However, this requires access to resources and might lead to unwanted consequences like exclusion, additional financial loss, and loss of future business. In the recent case of Los Angeles gallery CB1, artists who said they had obtained legal judgments against owner Clyde Beswick still weren’t paid, and his gallery will soon close due to slow sales and an expansion that overextended him.

So what on earth are artists to do?

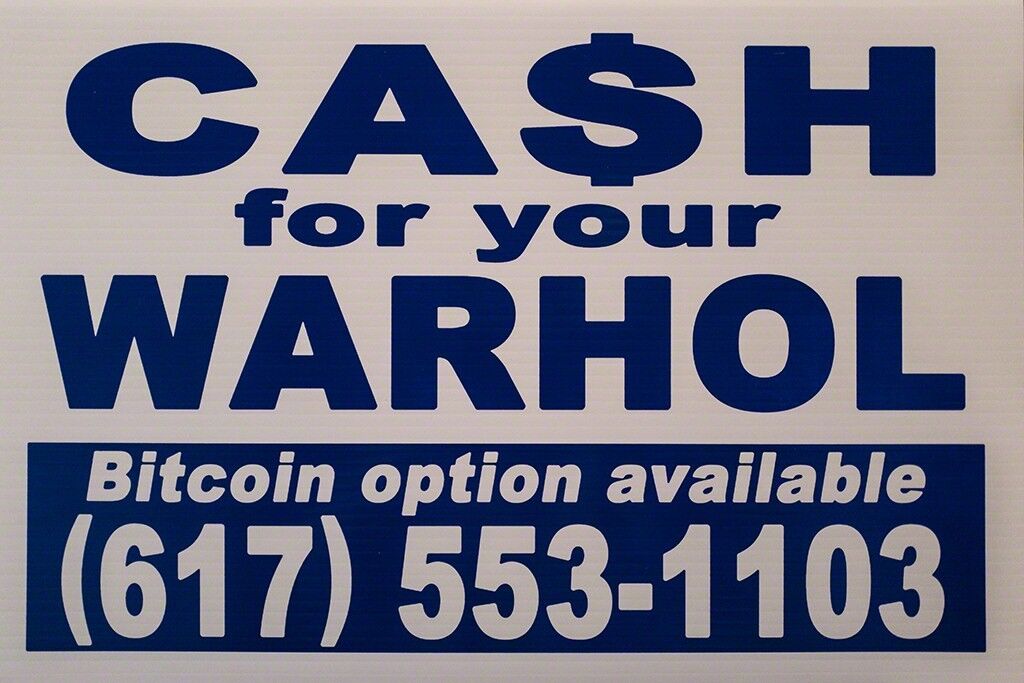

Tobias Vielmetter-Diekmann—founder of WrkLst, which creates inventory systems for art businesses—and I believe smart contracts can solve this problem. Smart contracts are self-executing contracts with the terms of the agreement between buyer and seller written directly into computer code. The code and agreements contained therein usually exist across a distributed, decentralized blockchain network, such as Bitcoin, Litecoin, or Etherum. No central authority, legal system, or external enforcement mechanism is needed to underpin smart contracts, since they themselves operate as executor and efforcer.

Smart contracts are already in use in sectors ranging from banking to healthcare to real estate. Dubai recently announced that, by 2020, all government documents would be secured with blockchain. Likewise, Sweden is currently testing the use of blockchain to digitize its land registries. And though smart contracts often employ blockchain technology, they do not need blockchain to operate. In fact, the concept of a smart contract was first proposed in 1994, 10 years before Bitcoin even existed, and has been used by operating systems such as Askemos since 2002.

In our field, a smart payment platform could streamline and demystify the transaction between artists, galleries, and collectors.

But how would it work? Imagine something akin to Airbnb for the art world, where instead of posting vacation rentals on a public forum, artwork would be bought and sold in private personal transactions. Just as a homeowner would post about a room for rent, an artist or dealer would upload information about available works onto the platform. The artist or dealer would then invite a client to view one or many of these works online, which would include relevant information such as the image, dimensions, medium, and sales terms (including price, percentage netted, and production fees to be reimbursed).

Once a collector commits to purchasing a work, the smart contract would go into effect. Final adjustments to terms may be made. Perhaps for this particular sale, the artist agrees to share a 15% discount with the dealer, instead of the usual 10%. Or the collector is given four weeks to pay instead of two; or an advisor is paid 10% for her or his services; or the collector is charged an additional shipping fee.

Once these adjustments are finalized—which would be as easy as changing the price, availability, or min/max rental time on your Airbnb post—payment is collected from the collector’s bank account, credit card, or digital wallet. This payment goes into escrow until the collector receives the work and marks it as received. Once this has happened, the artist, gallery, and consultant are paid simultaneously. This, by the way, is exactly how Airbnb, eBay, and many other platforms work, collecting money from the purchaser at the beginning of the transaction and delivering it to the seller once the transaction is complete.

How come such a service hasn’t taken off already? There are a few reasons. The main one is that collectors would lose many of the advantages they have right now: to pay whenever they want, cancel sales without repercussion, forgo sales tax by declaring out-of-state shipping addresses, and pay through shady means. In Georgina Adam’s new book Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century, she mentions an artwork that was paid for by 17 different bank accounts. Such tax avoidance or money laundering schemes would not be possible through the proposed payment platform.

Dealers may fear that these harsher terms would scare away their whale collectors and lead to a less liquid market. Galleries may also be reluctant to use such a platform because they would have to turn to banks instead of the money owed to artists for credit lines. Furthermore, there is a culture of excluding artists from discussions of money, so there would be a sizable learning curve for artists as they become fluent in financial jargon and get comfortable creating contracts for themselves. Lastly, many artists prefer to have someone else deal with their financial lives, in order to have more time and space for creative ideas. These are all genuine obstacles to realizing such a service.

Nevertheless, utilizing a well-designed payment platform should be no more alienating or time-consuming than booking a room on Airbnb. Also, honest collectors and dealers need not fear such a payment platform, since there are upsides for them, as well as for artists. Contingencies could be incorporated into the contract that would protect the collector if the work arrived damaged or different in any way from what was offered. For example, the collector could get automatically reimbursed, either partially or entirely, if the work arrived damaged. As for galleries, if collector payments were more reliable, it would reduce the need to “borrow” money from artists by holding onto their payments. At the very least, having more accessible, easily analyzed evidence of consistent cash flow could help galleries access traditional bank loans.

Most importantly, artists could play an active role in defining the market conditions of their work. The contract would more broadly provide greater transparency, which is important for the weaker parties in the transaction, which can sometimes be the dealer or collector, but is most often the artist. It also makes transacting far more convenient. Condensing the sale of an artwork into one action, rather than three or four spread-out ones, is more efficient. Instead of there being a verbal commitment from a collector to purchase a work, followed by an invoice from the dealer emailed several days later, followed by a check mailed to the gallery several weeks later, and eventual payment to the artist several months later, there would be one automated transaction whose terms would be known by all involved parties.

The time saved transacting could be put toward meeting new clients, discovering new artists, or making art, depending on who you are and what you do. Smart contracts would not replace any existing entities of the art market (except, perhaps, a few lawyers), but they would help streamline existing processes for artists, dealers, and collectors, whose energies can then shift to the more pleasant, creative, and personal elements of such transactions.

Tobias Vielmetter-Diekmann is the founder of Wrklst, an inventory management system for the art industry.

Mieke Marple is an artist based in San Francisco

No comments:

Post a Comment