Creativity

We Asked an Expert to Interpret Famous Artists’ Handwriting

Alfred Stieflitz, Photograph of Georgia O'Keeffe, seen nestled on a cushion on the ground, with her sketchpad and watercolors by her side, 1918. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Ever wondered what the handwriting of your favorite artist says about their life or work?

“In many ways, handwriting serves as an extension of an artist’s process,” says Mary Savig, the curator of manuscripts at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. “An artist might pen a letter just as she or he might draw a line. With this in mind, writing a letter can be an artistic act. In carefully composed letters, artists choose the penmanship style, utensils, and paper that will convey their creative inclinations.”

Graphology—the study of handwriting—has received a fair share of criticism since formally surfacing in the 18th century (it’s frequently branded a “pseudoscience”). But the process of gleaning insights about an individual from the way they write is still an active practice, one that provides delightful food for thought.

The artistic scrawls of figures like Pablo Picasso, Vincent van Gogh, and Frida Kahlo—individuals who have become subjects of endless intrigue—are particularly ripe for amusing analysis. While in many cases graphology cements what we already know about these heavily researched personalities, it also surfaces curious and eccentric details—like van Gogh’s tendency to leave his Ts uncrossed.

We caught up with certified master handwriting analyst Kathi McKnightand asked her to review writing samples from five famous artists. Below, she share insights into what may lie between the pen strokes of some of art history’s favorite artists.

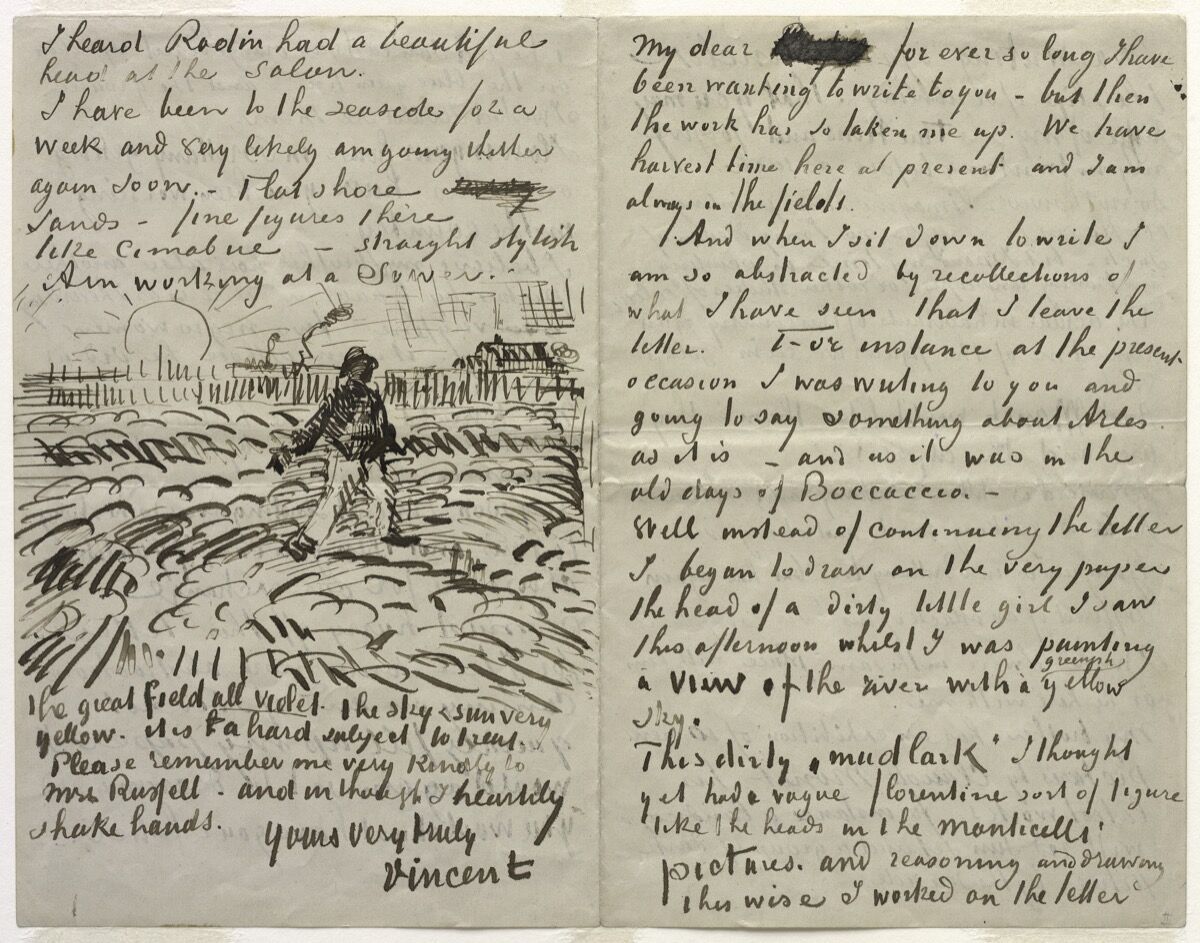

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh, Letter to John Peter Russell. Courtesy of The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art Resource, NY.

Van Gogh wrote a letter to his friend, Australian painter John Peter Russell, in mid-June of 1888, when he was 35. In slightly slanting, elegant script, he relates that he’s been meaning to write, but has been consumed by work; it’s harvest season in Arles, and he’s “always in the fields,” which is reflected in the charming line drawing on the left side of the letter.

McKnight points to way the artist’s personal pronoun I indicates the isolation van Gogh felt. “There is an emotional disconnect and distance,” she offers. Another notable clue is the word “present,” which trails off into the far-right margin—a possible sign of depression, McKnight says.

While noting the way the artist habitually fails to cross Ts or dot lowercase Is, she points to his signature (located below the drawing on the left) as a point of contrast. “When he signs his own name—our names are our own personal calling card—he steps into his personal power,” McKnight says. “The pressure is strong and clear. He completely remembers to cross his Ts, and with pressure (meaning determination). He dots his I strongly and succinctly [in his signature], and precisely above the I stem.” The enlarged size of his signature, she adds, further demonstrates van Gogh’s confidence.

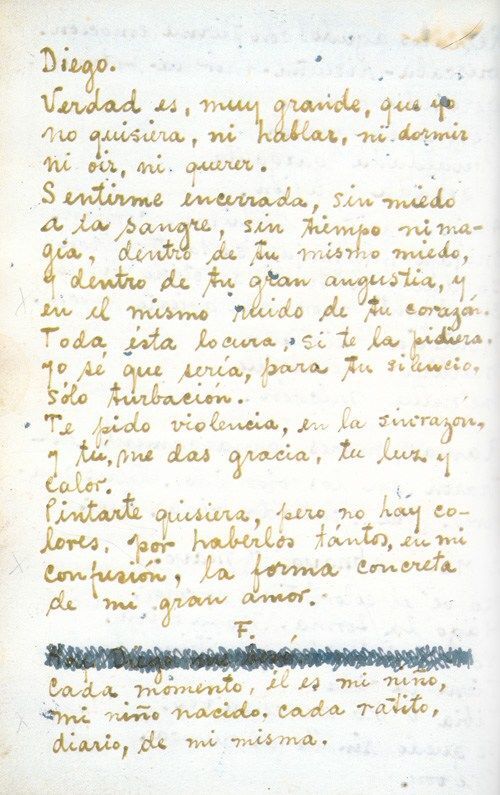

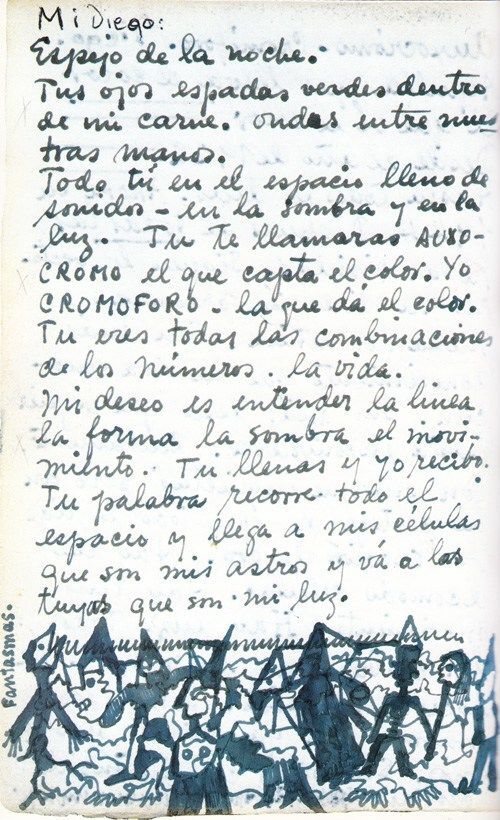

Frida Kahlo

Letter fromThe Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait. © Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Letter from The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait. © Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Throughout her tumultuous three-decade relationship with Diego Riverathat began in 1927—it included affairs among both parties, marriage, divorce, and remarriage—Kahlo kept a diary, in which she would write passionate letters to her beloved. Two of these letters, drawn from a 2005 book of the artist’s romantic correspondence with Rivera, are filled with dramatic odes (“I’d like to paint you, but there are no colors, because there are so many, in my confusion, the tangible form of my great love”).

McKnight remarks on the legibility of the artist’s writing. “She does not rush through or write with haste; the writing is deliberate and methodical,” she explains. The way that the Is are dotted, “with deliberate, definite pressure” she notes, shows “consistent attention to detail.”

The stems of Kahlo’s Ps, McKnight says, which reach high above the loops of the Ps, “definitely reveal intellectual probing.” And finally, “flat-topped Rs show very good hand-eye coordination.”

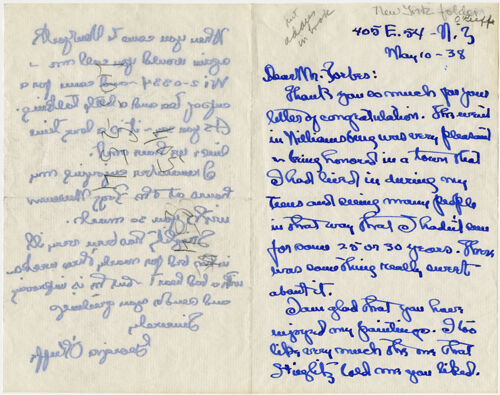

Georgia O’Keeffe

Letter from Georgia O’Keeffe to Edward Forbes, May 10, 1938. © 2013 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In brilliant blue, curlicue letters, O’Keeffe wrote to Edward Forbes, a former director of Harvard University’s Fogg Museum, in May 1938, at the age of 50. She expresses her thanks for a letter of congratulations that Forbes had sent her, and invites him to visit her and her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, the next time he’s in New York.

O’Keeffe wrote with an unusual trait that is “rarely seen in modern times,” McKnight notes. “Notice the unusual parallel strokes in her letters D and T in the words ‘honored,’ ‘lived,’ ‘about,’ and ‘sweet.’” McKnight refers to this stroke as the “master craftsman,” and notes that it has been associated with “one who is a perfectionist in their work.”

She also points to the artist’s “T-bars,” or the way she crosses her Ts: long, thin lines that at times exceed the length of the word, (for example, in “town,” and “that”). This, McKnight notes, can be revealing of “intermittent periods of extreme confidence and charisma.”

Finally, McKnight points to the large “P buckles,” the circles in the letter P—in “pleasant” and “people”—which could indicate that O’Keeffe possessed “a higher than average sex drive.”

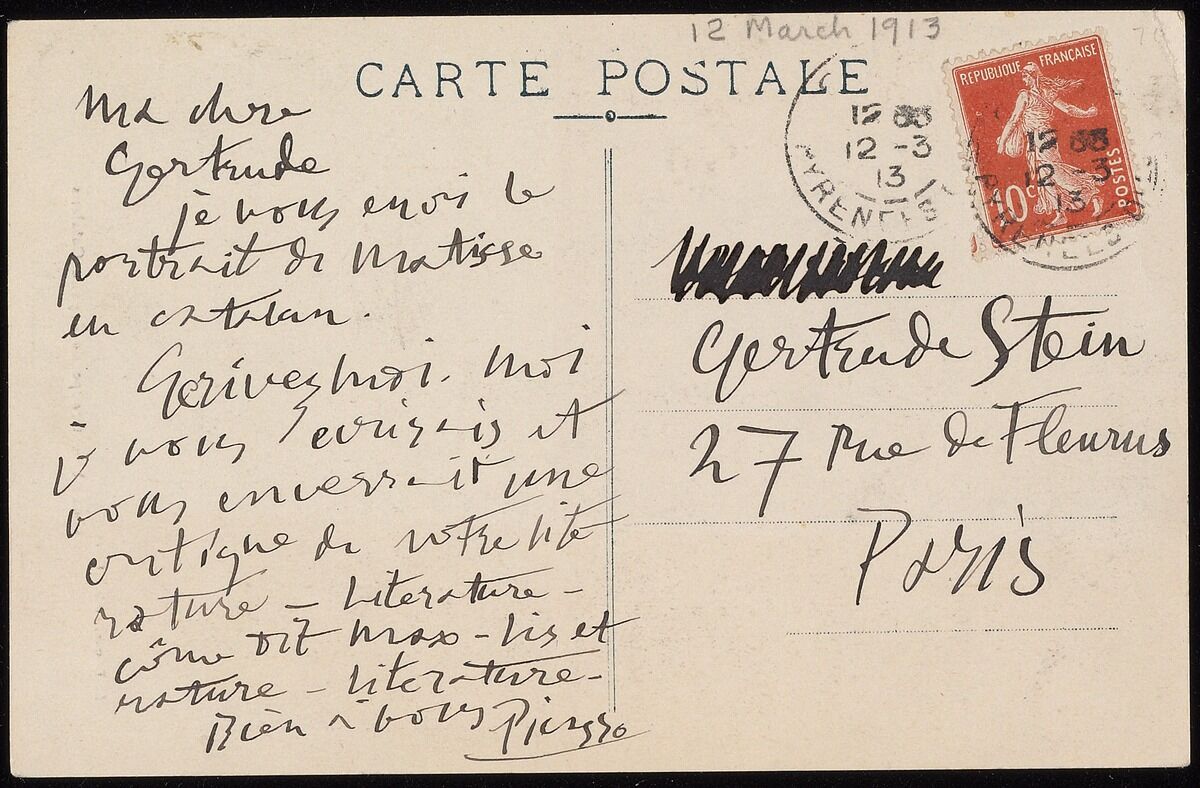

Pablo Picasso

Letter from Pablo Picasso to Gertrude Stein. © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Picasso wrote to his friend in Paris, writer and art patron Gertrude Stein, in March of 1913. At the time, the artist was living in a French town in the Pyrenees with one of his lovers, Eva Gouel. On the postcard, he writes playfully, joking that the photograph on the front (depicting three Catalan men drinking), includes a “portrait of Matisse as a Catalan.” He then asks Stein to write to him, and tells her he will write a review of her literature.

The brusque, hasty nature of the handwriting, McKnight says, suggests that Picasso “trusts himself to shoot from the hip” and “writes with haste.” His writing lacks the purpose, conscientiousness, and “careful, deliberate strokes” that can be seen in the handwriting of Michelangelo. “He’s in a hurry to get his thoughts down on paper, and his mind works very quickly,” she explains, adding that the script also suggests Picasso was feeling optimistic at the time.

Like O’Keeffe, the artist crosses his Ts with long, sweeping lines, which, McKnight says “reveal definite charisma, confidence, and a lot of emotional energy.” Additionally, the tent-like shape of his Ts may indicate stubbornness, while his Ms and Ns point to intelligence.

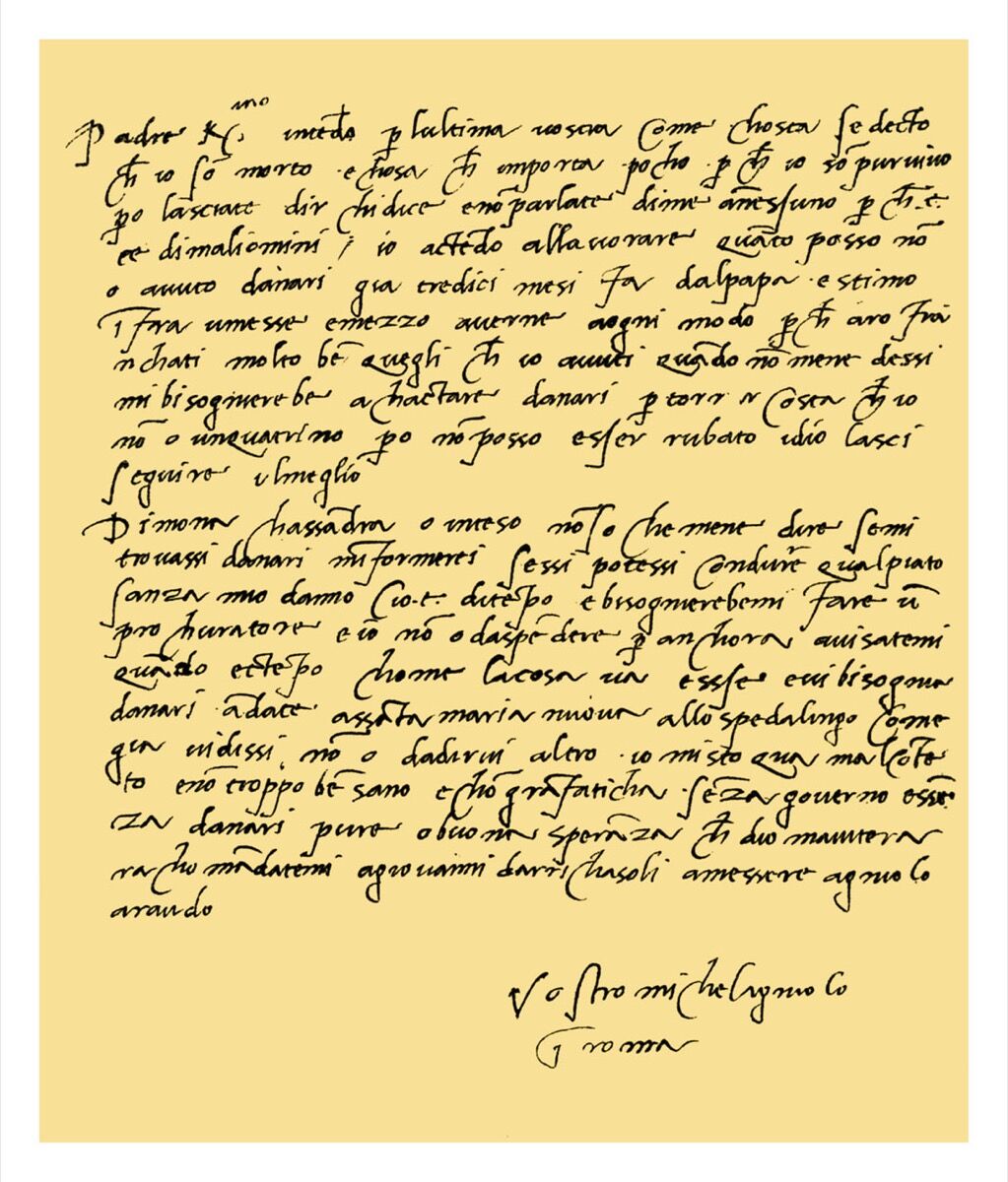

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Letter from Michaelangelo Buonarroti to his father, June 1508. Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images.

The Renaissance master Michelangelo wrote the above letter from Rome in June 1508 (as he was beginning work on the Sistine Chapel) to his father, Lodovico di Leonardo di Buonarroti di Simoni, in Florence. In his careful, almost calligraphic script, the artist assures his father that a rumor of his death is untrue and laments that he has not been paid by Pope Julius II, for whom he was working at the time, in over a year.

McKnight remarks on the “artistic, almost musical” nature of Michelangelo’s handwriting, and points to the exacting and even baseline, which can be seen as a sign of stability. The many breaks within words, and between letters, can be a sign of extreme intuitiveness. Additionally, the small, intricate text nods to the artist’s powers of concentration.

“Many of the ending strokes to the last letters of words go up at a 45-degree angle, which specifically reveals a mindset of courage and a mindset of not seeing problems, only solutions,” McKnight concludes.

Casey Lesser is an Editor at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment