Conceptual art gets a bad rap. It’s the butt of endless jokes. Works of this genre that were nominated for the high honor of the Turner Prize were called BS by the U.K. culture minister. Shia Labeouf used it as an excuse to put a bag over his head. So why is conceptual art so confounding? How do curators make it palatable? And what are we even talking about when we talk about “conceptual art”?

What Is Conceptual Art?

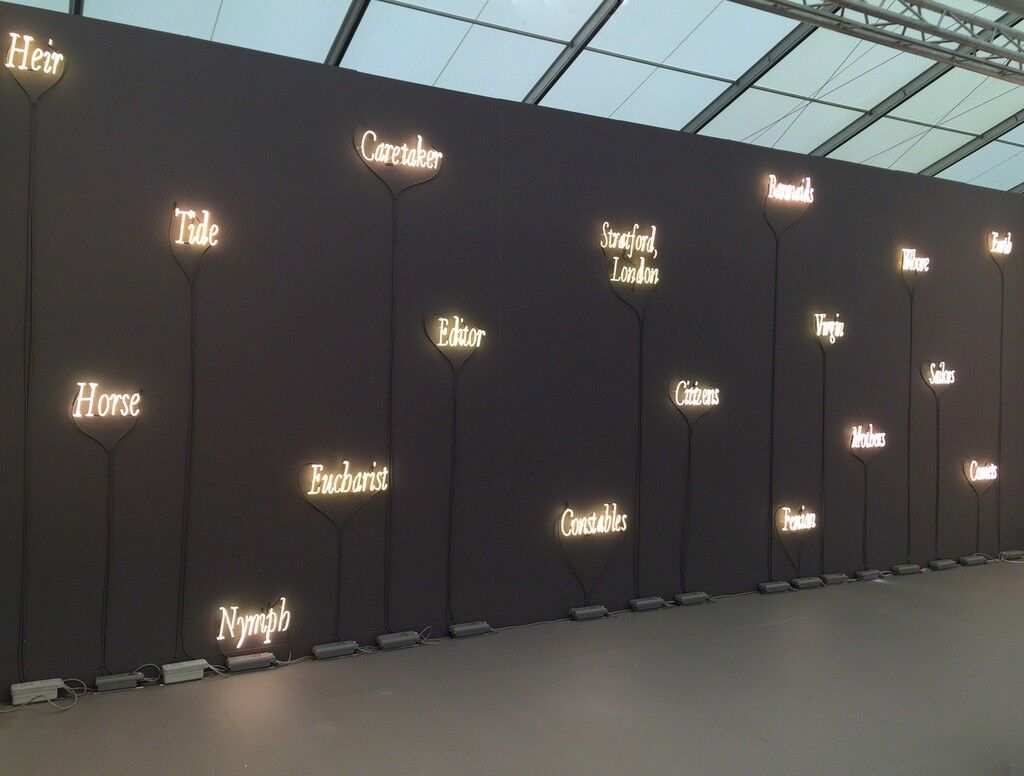

“It’s not a movement, it’s not a style, it’s a set of strategies,” says Andrew Wilson, curator of the Tate’s upcoming exhibition “Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979.” One can see the rub instantly: A “set of strategies” is a spot-on description, but hardly a straightforward one.

Conceptual art—its Western variant anyway—emerged in the 1960s as a reaction to Clement Greenberg’s militant commitment to formalism and art that concerned itself with the flat surface of the picture plane, such as Abstract Expressionism. Sol LeWitt laid out the terms for conceptual art in his seminal “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” published in the June 1967 issue of Artforum. “In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work,” LeWitt wrote. “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair.” That planning is, essentially, a set of strategies.

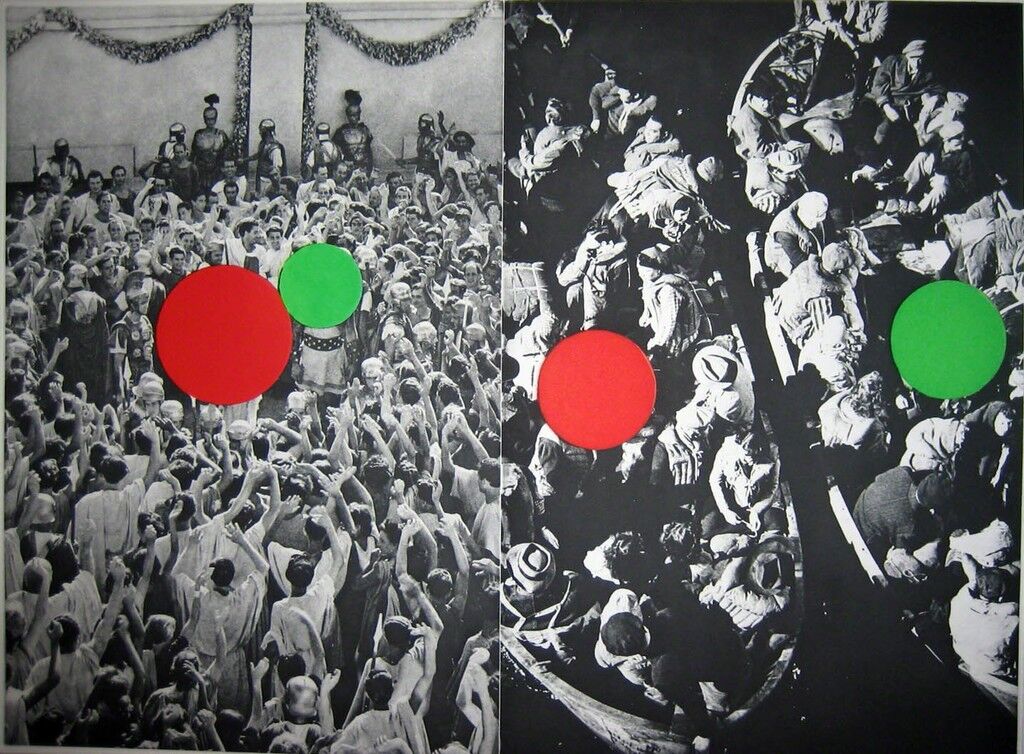

But isn’t all art planned with a concept? The nebulous taxonomy of conceptual art isn’t easy, even for the experts. Jens Hoffmann, deputy director of exhibitions and programs at the Jewish Museum, told me he long pondered similar questions himself, though a meeting with John Baldessari offered some clarity. A towering figure at 6 feet 7 inches, known for, among other things, putting dots on faces, Baldessari told him that “conceptual art wasn’t about art that had a concept, but about interrogating the concept of art,” as Hoffmann recalls.This interrogation, not confined to any one medium, has historically been seen as the province primarily of white men (we’ll revisit this glaring issue later). Among the touchstones of early conceptual art are Bruce Nauman, Joseph Beuys, Eva Hesse, and Joseph Kosuth, whose One and Three Chairs (1965) features a physical chair, a photograph of that chair, and the dictionary definition of a chair. It’s what you’ll see in any Art History 101 class and it’s guaranteed to make students’ eyes roll—and not without good reason.

Curating Conceptual Art

The self-reflexive underpinnings of Kosuth’s work run dangerously close to reinforcing art as the domain of an elite few with the requisite knowledge. Indeed, the experience of engaging with conceptual art is often marked by the suspicion that the work’s central, revelatory idea is somewhere in your mind’s peripheral vision, just out of sight. A bad conceptual work makes you feel that the idea isn’t worth finding. A good one spurs you to keep searching. Why did Maurizio Cattelan hang every work of art he’s ever created from the ceiling of the Guggenheim? It’s a funny but cerebral question that’s likely to leave visitors puzzling, and happily so, for some time.

Providing a viewer the information to get to that central thought, or set of strategies, without overwhelming them is a perpetual challenge, but curators confronting how to make conceptual art digestible without inducing a tummyache must tackle it. Hoffmann, who has staged ambitious re-thinks of seminal conceptual art exhibitions like “Other Primary Structures,” recommends a balanced diet of programming, tours, and didactics (aka, words that tell you things). But the strategy isn’t without peril. The wall texts that accompany conceptual shows can grow dense “to the point at which the artwork becomes difficult to see,” as Wilson puts it.

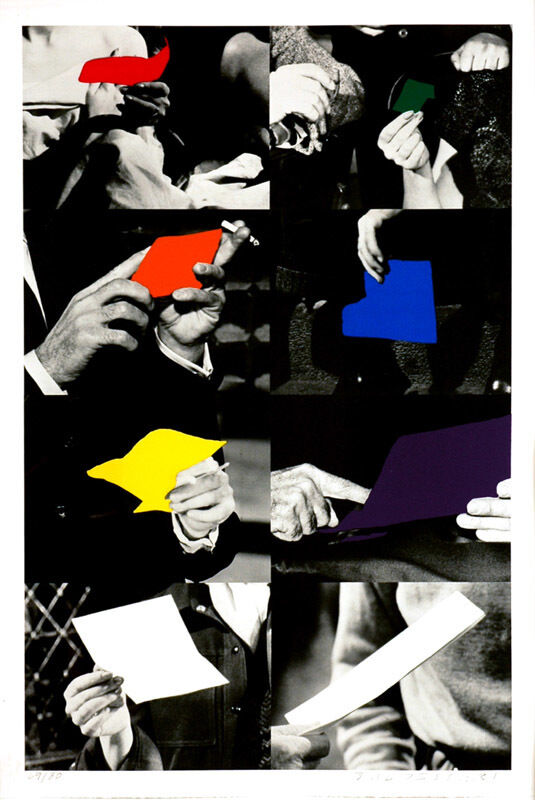

John BaldessariHegel's Cellar: Two Boats1986Diane Villani Editions

Ideally, wall text is superfluous. In the late 2000s, curator Leslie Jones of LACMA worked in conjunction with the the Tate’s Jessica Morgan to mount “John Baldessari: Pure Beauty,” a major retrospective of the artist’s work that traveled around the globe. “Baldessari’s work is very clear,” Jones told me. (“Clear” is not often a word one hears used to describe conceptual art.) Sometimes pared down to just words scrawled on a canvas, the tongue-in-cheek pieces were effectively their own wall texts. “Humor puts people at ease. They laugh first and then they start thinking,” Jones said.

Conceptual Art in the World

Baldessari’s visual language challenges the perception that conceptual art is either wholly the domain of the over-informed (Kosuth) or of those hungry for vapid spectacle (Koons). “In the ’60s, when [Baldessari] was first leaving painting behind, he wanted to talk to people in a language they understood,” Jones told me. “And for him that meant text and photographic image. That seemed the most democratic.”

Even in the founding document of conceptualism, one finds an impulse towards populism—or at least the recognition that it is people who make meaning. That may seem strange given that conceptual art today is often viewed as hermetic, self-reflexive, and impenetrable except to the mind that divined it. But “once it is out of his hand the artist has no control over the way a viewer will perceive the work,” LeWitt wrote. “Different people will understand the same thing in a different way.”

And that “thing” wasn’t a flat splatter canvas but bits and pieces of the real world. It’s a fact that Wilson wants to impress upon viewers when they see “Conceptual Art Britain,” which opens in April. “One of the things that I would very much hope people might come away from this exhibition with is actually understanding how engaged [conceptual art] is with the stuff of everyday life,” he told me.

Case in point: Roelof Louw’s Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges) (1967). The conceptual work is part of an art-historical dialogue about form (“against the modernist ideas of geometrical syntax,” says Wilson), but it is also a pyramid of 5,800 oranges. As they rot or are taken away by visitors, the geometry shifts and changes, thanks to the organic processes, be they our hands or the passage of time. Go on, eat one—it’s a good idea.

Conceptual Art’s Legacy

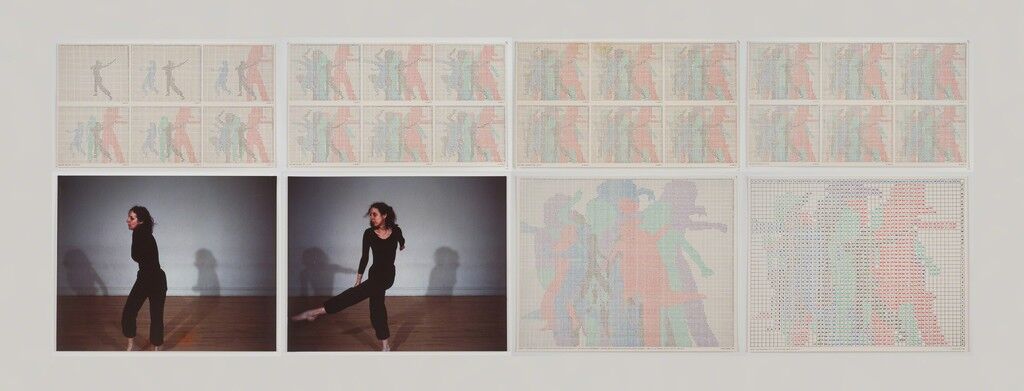

For all its navel-gazing, conceptual art also tackles issues of authorship, time, space, identity, and even ownership (how do you buy a concept?)—themes that have very tangible manifestations in the real world. Anyone can employ the instructions that LeWitt used for his art (he often used assistants himself) and create a perfect geometric wall drawing, but trying to hang your DIY conceptualism at the MoMA is not recommended. Still, the question is raised: How is authorship ascribed? Conceptual artists “were putting the condition of the art object in question,” says Wilson, “but in doing that they were taking the strategies that they’d evolved to put the condition of society in question as well.”

Trying to craft entirely self-referential works of art is doomed to fail anyway, either because viewers will be bored to tears or because the work will be unable to escape the world outside of the museum. But ultimately, it’s that outside world that can lend conceptually minded art its meaning and value. Around the same time that Thelma Golden’s “Black Male,”—a now-iconic exhibition that the New York Times once derisively called “slanted toward conceptual political work”—opened at the Hammer in L.A., the O.J. Simpson trial began in the city. A courtroom is no more hermetically sealed from the broader context in which it exists than a museum or piece of conceptual art is, and Golden’s exhibition has become a hallmark for how art can parse pressing political conditions.

Indeed, despite all the claims made to conceptual art’s intellectual purity, broader societal inequity is partly why it was historically dominated and defined by white men. No doubt more study will reveal overlooked minority and women artists forced to practice conceptual art outside the lens of art history’s white microscope. But regardless, subsequent politically engaged and inclusive modes of artmaking that harnessed some of the tools of conceptual art, like feminist art, institutional critique, and performance art, have explicitly looked for meaning beyond the white walls. Where conceptual art ends and those movements begin is difficult to say.

During a panel about black conceptualism at the Hammer, artist Rodney McMillian spoke of the relationship between Charles Gaines and Sol LeWitt. Though rooted in conceptualism, Gaines’s practice expands on LeWitt’s foundational paragraphs, he said, opening them up to include ideas around representation in art so that “there could be space for artists of color and gendered minorities.” When LeWitt died in 2007, Gaines sent around a message with a few thoughts, which McMillian shared with those who had gathered to hear the talk. “Sol was the most generous person I know,” the message read. “His passing leaves an enormous hole for me personally and I dare say to the world of contemporary art.”

Isaac Kaplan is an Associate Editor at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment