How to Declutter Your Studio for Maximum Creativity, According to Marie Kondo

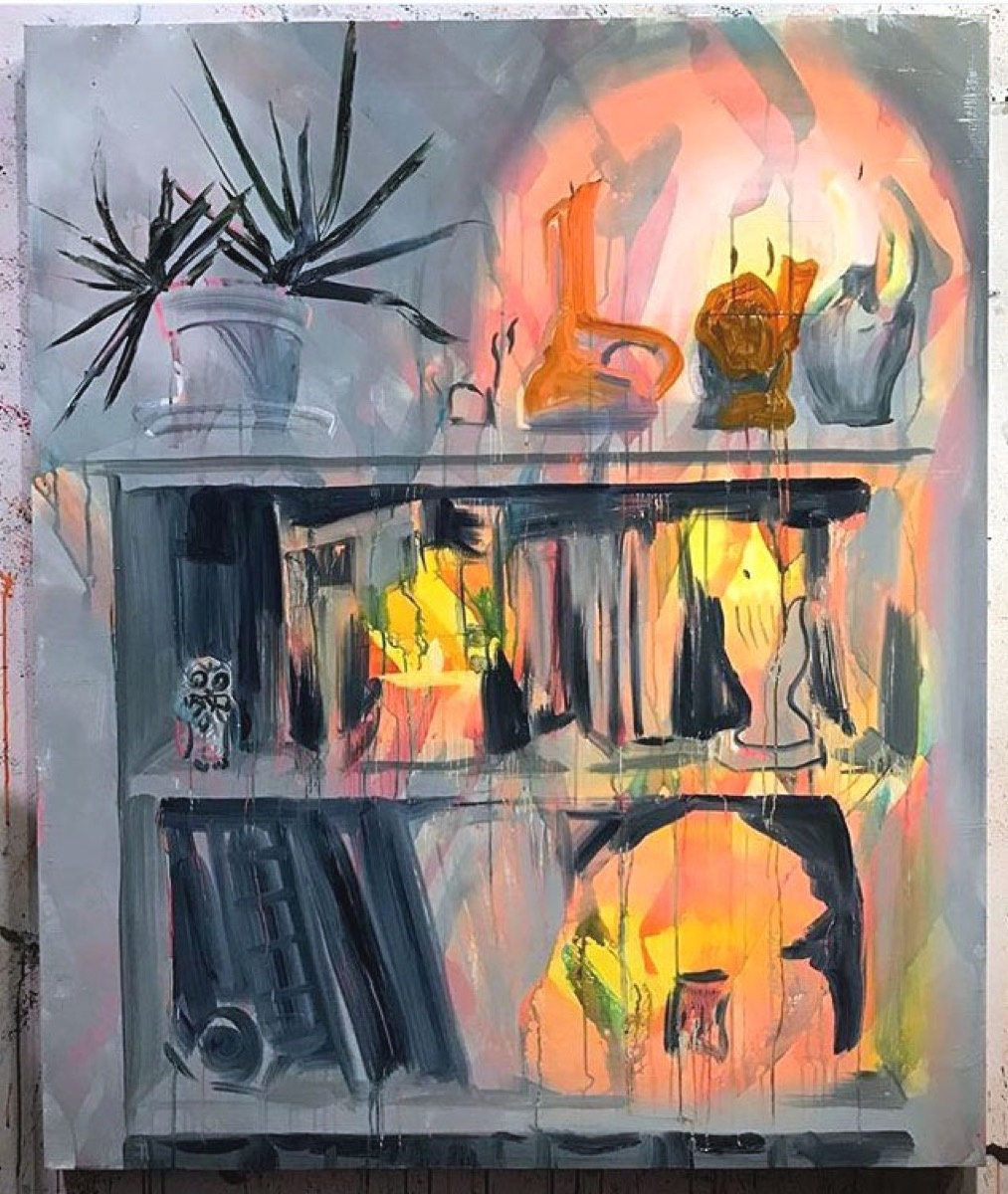

Detail from Betty Tompkins’s New York studio. Photo by Emily Johnston for Artsy.

Detail from Betty Tompkins’s New York studio. Photo by Emily Johnston for Artsy.

If you close your eyes and imagine an artist’s studio, chances are you will picture a messy room. Perhaps its walls are stacked with canvases, or its floor a tangle of wires and cables, with teetering piles of books, all covered in the rubble of plaster casts. There’s a certain mystique attached to messy artistic types, as if true creativity is only possible amid chaos.

However, Marie Kondo, author of The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, sees artmaking and organization not as opposites, but as kindred pursuits. “The depth of concentration and the respect for materials involved in creating artwork is similar to the focus and connection with belongings associated with tidying,” Kondo tells me via email. As an undisputed expert on tidying, she should know. The Tokyo-based organizing guru’s books have sold over 7 million copies, and her consultations currently have a six-month waiting list.

Kondo’s trademarked KonMari Method is based on Japanese philosophy and unsparing minimalism: Any object that does not “spark joy” should be discarded. The desired result is that we will be surrounded only by things that inspire and delight us.

Because she believes that art and organizing can be simpatico, I asked Kondo to share her tips for how artists can better organize their studios. I also asked artists who work in a variety of media to weigh in on the challenges and rewards of what Kondo calls “the art of tidying.”

1. Understand what kind of environment most inspires you

Rachel Grobstein, Ajax, 2015. Courtesy of artist.

Rachel Grobstein, Ajax, 2015. Courtesy of artist. Rachel Grobstein, Eggs and Toast, 2015-16. Courtesy of artist.

Rachel Grobstein, Eggs and Toast, 2015-16. Courtesy of artist.

Does a cluttered workspace spark new ideas or just make you anxious? “There have been instances where individuals who thought they thrived in a messy state actually prefered the comfort of tidiness once they had completed the KonMari Method,” Kondo says. “On other occasions, artists ended up uncovering many more things that sparked joy for them in the process of tidying, and enjoyed their scattered space more than ever.”

For many artists, a “scattered space,” one full of objects that are arranged according to some rationale, can serve as a vital source of inspiration. Rachel Grobstein, whose sculptures are constellations of tiny objects precisely rendered in gouache on cut-out paper, uses one wall of her studio as a sort of atlas or scrapbook. “It’s the place where I can put a Masonic beer koozie next to a tumbleweed, an image of Basquiat’s notebooks, and a pin given to me by my grandmother,” she explains. “The stuff I’ve collected serves multiple purposes: It presents a visual web of my interests, connects me with threads far away and long ago, and sparks new associations.”

Sometimes disorder can spark ideas, too. For artist Sophia Narrett, piles of clothing and even wads of used tissues have prompted ideas for her complex embroideries, which often tell stories about love and desire. “Clutter can be a good narrative clue,” she explains. “It has always accumulated for a reason.”

2. Treat tidying as an important project and give it your full attention

José Lourenço, Let's paint...!, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Things Organized Neatly.

José Lourenço, Let's paint...!, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Things Organized Neatly.

“I recommend that artists dedicate a block of time to organizing their studios—perhaps an entire day—to tidy up all at once, rather than tidying little by little over many days,” Kondo says. In her experience, it’s important to reject the conventional wisdom that tidying should be approached piecemeal. “By tidying with concentration, the ability to decide which tools and materials spark joy will become clearer,” she notes. “It will be easier to take inventory of all the categories of items an artist owns in one sitting.”

Organization is important if for no other reason than that a disorganized studio can lead to a loss of income. As artist Jason Peters points out: “There should always be a certain amount of order in your space because art is a business.” Peters, who creates large-scale installations from mass-produced and found objects, notes that being an artist usually entails a considerable amount of multitasking, and a tidy studio can help when it comes to running things smoothly.

“These days artists have to wear many hats,” he says. “We not only have to consistently create work, but manage a web presence, network with galleries and collectors, and find new avenues to show work.”

3. Categorize your materials and tools, then divide and conquer

Detail from Genieve Figgis’s County Wicklow studio. Photo by Doreen Kilfeather for Artsy.

Detail from Genieve Figgis’s County Wicklow studio. Photo by Doreen Kilfeather for Artsy.

“Artists’ belongings could be roughly divided into two categories: ‘Materials,’ or things that can become part of the artwork, such as cloth, thread, buttons, and clay, and ‘Tools,’ such as needles, color palettes, and patterns,” Kondo says. “If artists have many things to tidy, they can create subcategories, for instance dividing ‘Tools’ into ‘Brushes’ and ‘Threads.’” She recommends that each category be tidied completely before moving on to the next.

Sophia Narrett categorizes her embroidery thread by color, which keeps the tangle-prone material relatively in check. “I use the lids from large plastic storage bins as palettes. One holds blues, one is for greens, another is reds, pinks and purples, the fourth is yellows and oranges, and the fifth is neutrals,” she says. “I’ll sort them when I begin a large piece, but as the piece develops the palettes get progressively wilder.”

4. Keep only materials that spark joy and let go of the rest

Rachel Schmidhofer, wax owl, 2017. Courtesy of artist.

Rachel Schmidhofer, wax owl, 2017. Courtesy of artist. Rachel Schmidhofer, Rox, 2015. Courtesy of artist.

Rachel Schmidhofer, Rox, 2015. Courtesy of artist.

In The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, Kondo suggests holding each object, asking yourself if it sparks joy, and discarding anything that doesn’t meet that standard. She specifies that “an artist might determine which materials spark joy by imagining how they would feel using them in future projects.”

For painter Rachel Schmidhofer, this question presents the biggest organizing challenge. “Which objects are actually generating ideas and which ones are an impediment to the physical and mental clarity I need to make the next thing?” she wonders. Schmidhofer’s still lifes and domestic scenes are deceptively calm—a goldfish lazing in a fishtank or crystals displayed in a specimen box—but their surfaces are often drippy or jittery, suggesting a tension between order and disarray. “I’ve started to view the inside of my studio as a reflection of the inside of my mind,” the artist says. “There’s definitely a relationship between clutter in my space, anxious thoughts in my brain, and scatteredness in my paintings.”

5. Always remember to thank your work

An essential element of Kondo’s method is showing appreciation for the objects we use and enjoy. “It’s a good practice to express gratitude toward artwork, whether out loud or in your heart by saying, ‘Thank you for making me happy,’” she tells me.

This appreciation for objects and the suggestion that they have an inner life is a familiar idea to many artists. Peters is sensitive to the sadness of neglected things and observes that “if you have objects that are not picked up and touched, you can almost sense their unhappiness at collecting dust.” Schmidhofer, on the other hand, wonders what our clutter is saying about us behind our backs: “Sometimes when I open someone’s refrigerator door it almost feels like I can hear the echo of the old, half-empty condiments chattering to each other. I love to think about what societies of objects might talk about when people aren’t listening.”

Kondo also suggests that artists might find it rewarding to send their work out into the world already imbued with feelings of gratitude. “The artist can send positive energy to the people who might buy or experience the artwork,” she says. “For example, whenever I find my book in the store, I always pat the front cover and say in my heart, ‘Please make the person who purchases you happy.’”

—Ariela Gittlen

No comments:

Post a Comment