A so-called Chinese “urban village,” Dafen once produced an estimated 60 percent of all the world’s oil paintings. During its heyday—when the village’s reputation as an art factory rang truer than today—it almost exclusively cranked out copies of paintings in the Western art canon. These canvases found their way into hotel rooms, show homes, and furniture outlets all around the world. Not bad for somewhere that until the late 1980s was a largely overlooked and decidedly rural backwater on the periphery of Shenzhen.

Now, an array of factors, which in many ways mirror the larger picture of rapid Chinese economic development, have converged to threaten Dafen’s long-term viability. In response, the government is stepping in to try to change its image from a city of cheap fakes to a creative hub home to original artists making works to fill the homes of China’s rapidly growing middle class. But the future for these artists and artisans remains uncertain.

Building the World’s Art Factory

An entrepreneurial trade painter, Huang Jiang, launched Dafen’s remarkable trajectory. Upon moving his business in 1989 from his native and increasingly pricey Hong Kong across the border into mainland China, Huang recruited and trained additional, migrant workers to fulfill a glut of existing orders. Taking advantage of Hong Kong’s more mature infrastructure for practicalities such as shipping, Huang developed an assembly line process for art reproduction in Dafen.

Huang Jiang’s relocation of his business nearly three decades ago was opportune in several ways. Shenzhen proper was already a burgeoning Special Economic Zone (SEZ), a designation rolled out in the early 1980s as part of sweeping economic reforms that provide tax and business incentives in order to attract foreign investment. But in 1989, Dafen was positioned just outside of this lucrative region.

Although later swallowed up by the expanding SEZ in 2010, at the time, Dafen quite literally sat at the gateway to the massive export economy on which modern-day China was built. The result was fast urbanization thanks to incoming cheap migrant labor and Shenzhen’s sprawl. But in Dafen, grassroots, bottom-up industries—propelled by cheap labor and land—could develop away from the pressure cooker-like policies and conditions of the SEZ proper. For Dafen, that industrialization took the form of art.

At its peak, Dafen was jam-packed with sizeable, factory-like studios, all employing Huang’s production line process. Individual workers each focused on a specific compositional element—background details, or eyes, or trees—dutifully painting their part and then passing the canvas along the chain.

In the mid-2000s, Dafen’s copy industry was booming. It was at this point that auxiliary commercial avenues began to take root in the village. Quaint cafes, as well as more accessible “gallery shops” (predominantly fronts for anonymous art workers and addresses from which to tout for business both wholesale and retail) lent the village lucrative tourist appeal.

By the decade’s end, Dafen was well and truly on Shenzhen’s map, its success story absorbed into the city’s broader narrative. To that end, at the World Expo 2010 Shanghai, Shenzhen’s Urban Best Practice pavilion featured a mosaic of 999 panels painted by more than 500 art workers to recreate what was dubbed the Dafen Lisa.

Around the same time, Dafen began to see a dip in international demand, which—combined with rising property costs, plus China’s broader aspirations with regard to soft power—has resulted in complex, and sometimes conflicted, development. Throw into the mix the spending power and growing taste for art of China’s expanding middle class, and several distinct drivers soon emerge.

By far the loftiest ambition of the various players currently invested in Dafen is for the village to become an authentic creative hub, and above all a place for original art and culture.

Today, this branching of paths—from copy art, to original art, to shining national example—feels tangled. Case in point: During my stay, I was corrected and chided for referring to copyists as artists, or yì shù jiā in Chinese. They’re huà jiā, painters or art workers, and the difference in social hierarchy is made extremely apparent.

City at a Crossroads

I visited Dafen in March 2017, taking an hour-long subway ride north from the cosmopolitan bustle of Hong Kong. A large sculpture of a hand holding a paintbrush marks the entrance to the village: a gated development of just under half a kilometer square whose narrow streets are laid out in a grid. At its outer edges, sawdust mingles with the metallic clinking of hundreds of staple guns as framing stores prep a constant stream of blank canvases before stacking them in wooden pallets. Towards the village’s center, the wood smell is replaced by the distinctive headiness of oil paint and turpentine.

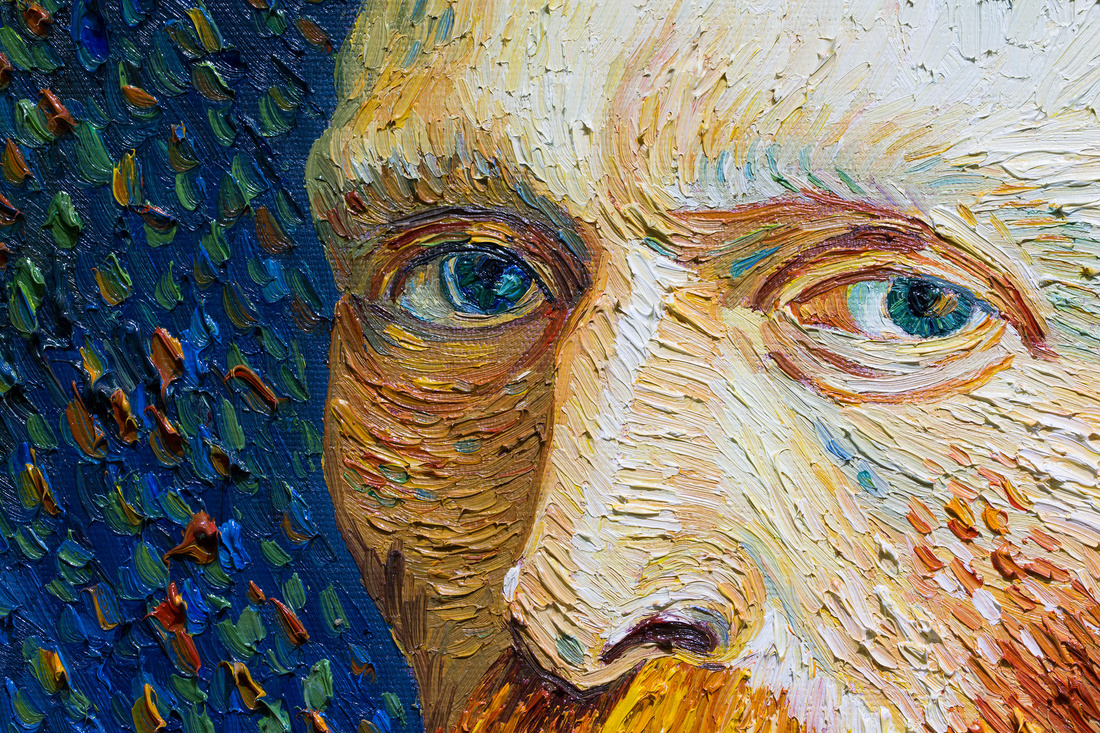

Around half of the low-level buildings accommodate stores selling a bewildering (but for the most part, homogenous) mishmash of paintings. Framed pictures of pastoral idyls, Van Gogh replicas, and photorealist portraits of Trump, Putin, and anonymous tourists cover every available inch of wall; canvases are stacked clumsily on the floor between layers of cling-wrap; and outside, tourists rifle through bargain bins of small paintings and prints priced from just ¥10 a pop (roughly $1.50).

Other storefronts are rented directly by painters—the working studios serving as a useful shop window for their respective niche, be it pets, Picassos, or Pop art. Case in point: Zhan Xin Xiang, who considers his diminutive studio space, shared with three artworker friends, to be a kind of advertisement. Loud music blares from the radio; all four men sit at canvases and meticulously copy images from their iPads. He explains that buyers for Chinese online art galleries—most of which reside on T.Mall, the B2C spin-off of e-commerce giant Taobao—frequent the village looking for talent. Such commissions earn Zhan in the region of ¥10,000 ($1,500) each month, he estimates.

There are also more conventional galleries, generally showcasing the work of—and often owned by—a single artist. One such space is Ease Gallery, established in 2006 by Ethan Lau, an artist and teacher from Huanggang, Hubei province. An exponent of Dafen’s more recent turn to artists creating original paintings, Lau says designers, homeowners, hotels, and clubs are the most frequent buyers of his large-scale ink works, inspired by traditional Chinese calligraphy. He also works with more studious collectors, he explains. (Lau declined to disclose how much he makes from his sales, but when I asked his staff the price of a particularly striking work on canvas at the gallery, I was told around ¥10,000.)

Surrounding these studios and galleries in Dafen are art supply stores and a handful of whimsical cafes, some of which offer painting classes to visitors. There are also a more workaday street-side sellers of málàtàng, a type of hot pot in which skewers of various meats and vegetables are cooked in a spicy broth; a Lanzhou noodle shop; a post office; and a primary school. It’s a dense, colorful, bustling place.

At the village’s eastern edge is the Dafen Museum: All angular grey slate, the impressive architecture is fronted by a plaza intermittently occupied by pop-up markets, careening children, and older generations performing evening exercises. Opened in 2007, the museum was built by Urbanus, the same Shenzhen firm behind the city’s ultra-contemporary OCT Art Terminal Shenzhen and Artron Art Center. The museum shows predominantly modern and contemporary art from China.

In stark contrast to the of-the-minute museum, an adjacent stone frieze some 30 meters in length depicts Western art classics: There’s a snippet of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, Picasso’s Dreamer, and a longstanding Dafen best-seller, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. Like the Old Master busts dotted about the village (Da Vinci is to be found staring beatifically at the primary school), the frieze points to Dafen’s candidness and pride in a global reputation founded on reproduction, even as it strives to be known for original production.

All signs point to an impending identity crisis.

A Shifting Economy

Replica Rembrandts and mock Modiglianis continue to serve Dafen well—in 2015 revenues in the village were estimated to be ¥4.29 billion ($630 million). However, its “global painting factory” moniker is now not only overwrought, but for the most part outdated. Production has declined as the internet and online retail has removed the necessity for its centralized form of production. Rising rent prices in Dafen itself have further exacerbated the issue, with a copy-art boom now occurring in cheaper cities like Xiamen and Yiwu.

Meanwhile, cheaper and more efficient production methods have been developed. Many copies are now first printed onto canvases in high-definition, after which art workers apply just enough paint to make it appear as if they were painted by hand, a process which requires significantly less skill and produces a more consistent result.

Among the remaining owners of large-scale production and export businesses in Dafen is Miles Tang, director of B&C Arts, whose business can be found on the e-commerce platform Alibaba. The Henan native first arrived in Shenzhen in 2001. He launched B&C in 2006 out of one of Dafen’s gallery shops. Finding the retail market to already be both saturated and fiercely competitive, a year later he switched his focus to international wholesale. This came at a precarious time: Many of Dafen’s sellers saw a significant downturn in international orders during the global financial crisis. But Tang’s business boomed.

Today, Tang rents a capacious factory some 20 minutes’ walk from Dafen proper. But despite its expansive floor space, only half of his workforce of around 30 painters is based there. The rest, he explains, have left Dafen for their respective, and generally more affordable, hometowns. Tang emails orders for artists to complete off-site and send in upon completion. At the factory, their finished canvases are rolled into compact shipping cylinders, with most winding up in furniture shops in the U.S. and Mexico. Tang estimates his operation’s total output is usually in the region of 500 canvases per week, with numbers reaching up to 1,000 during peaks in demand, such as Black Friday.

Some retailers benefited from an uptick in domestic trade when international market fell out in 2008: Today, hotel chains in China have become Dafen’s biggest customers. A four-story shop on a prime corner of Youhua Jie (“oil painting street”) claims both the Westin and the Marriott in Shenzhen as customers, as well as a host of interior designers in Hong Kong.

Xu Mei Juan, who owns another gallery nearby, explains that the increase in domestic trade can partly be attributed to a newfound appreciation of art among Chinese consumers. Roughly translated as “Starry Sky,” her business specializes in Monet and Van Gogh replicas, all painted by her husband.

“Between 2008 and 2010, most orders were coming from abroad. But now, I mostly sell to Chinese hotels and also regular customers,” she says. “For Chinese, it has become much more normal to have art hanging on your walls at home.”

In a village so abundant with Sunflowers, the heavily textured creations she offers are palpably superior—and notably more expensive—specimens. Xu quotes ¥1,000 ($150) for a framed painting measuring 30 by 40 inches, and estimates that, including drying time, each takes around 20 days to complete.

To a Westerner audience, the desire to vaunt what is so obviously a fake may be difficult to grasp. But in a Chinese context, it’s sobering to remember that for much of the country’s recent history, and in particular during the Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976, it was simply impossible for “bourgeois” artworks to exist. The government dictated that the only permissible art should be hóng, guāng, liàng, or “red, bright and shining.” And while such thinking may have since been resolutely stamped out in cities, the same still cannot be said for the Chinese countryside. As such, Xu’s domestic market continues to have room to grow.

Government Intervention Spurring Original Work

By far the biggest shift in Dafen’s recent history is the move toward promoting original art. Two things have driven this change. First, the aforementioned competition from cheaper locations offering comparable products, combined with a decline in global demand, is forcing painters who once worked exclusively in the field of copy art to diversify their offering. And rising rents mean these copies are no longer sufficient for survival; even with high domestic demand, their market value remains low.

As such, many painters have begun to create both replicas and original works, which they can sell for a higher price. The development isn’t always smooth, and there’s often friction with Dafen’s guard of original artists. Lau explains that plagiarism is rife.

“I have had embarrassment all these years because of copying, duplication, and even copyright breaches for printing my artwork in bulk. It never stops,” he says.

A more powerful catalyst for original art production has been the Shenzhen government, whose ambitions to pitch the city as a cultural center extend to Dafen. In 2004, the government launched an organization called the Art Industry Association of Dafen Oil Painting Village to promote initiatives such as the National (Da Fen) Youth Oil Painting Exhibition, co-organized by Longgang District committee since 2012, and a national Dafen art competition. It also acts as an umbrella association for Dafen’s participation at trade fairs and expos, including Shenzhen International Cultural Industries Fair, Guangdong International Hotel Supplies, and a Shanghai Furniture fair.

Beyond promoting the Dafen brand, the Art Industry Association of Dafen Oil Painting Village also supports the upgrading and diversification of the village’s art industry and recently hosted a meeting between its members and the e-commerce platform JD.com. Reinforcing how the internet and e-commerce in particular continues to shape Dafen, a representative explains that changing conditions have necessitated innovation on the part of Dafen’s workers, particularly by way of leveraging the internet as a sales channel.

“The traditional channel is not conducive to the development of oil painting. The business model has changed [so] Dafen oil painting village must also change,” he says. “Dafen enterprises engaging in e-business platforms is a trend.”

As opposed to the Western art market, in which online art sales outlets are typically seen to sell lower-end artworks most effectively, the association’s representative says that their interest in e-commerce retailers like JD.com is the access to more upwardly mobile consumers.

“The JD.com platform reaches high-end customer groups, so art as lifestyle, not only as culture,” he says.

The picture of Dafen today is far more nuanced than it once was, both in terms of opportunities available to its workers and the ambition the local authorities have for its future. The village is host to an ongoing negotiation between feeding a domestic market still hungry for the copied artworks it has long produced and recognizing that, in the very near future, that market may not be sufficient to support the artists who feed it. At times, the urban village’s future can feel extremely precarious.

As the cost of living rises, Dafen’s initial life force—its migrant painters—are most at risk. While the Chinese middle class may be growing rapidly, the shift from a volume-based model of selling cheap copies to businesses, to selling relatively much more expensive original paintings to consumers, will mean that fewer artists and art workers will be supported.

—Frances Arnold

Translation assistance provided by Mo Fanlin.

Cover image: An artist paints in his studio in Dafen. Photo by Adam Kuehl for Artsy.

|

|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

Friday, June 23, 2017

The World’s Art Factory Is in Jeopardy

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment