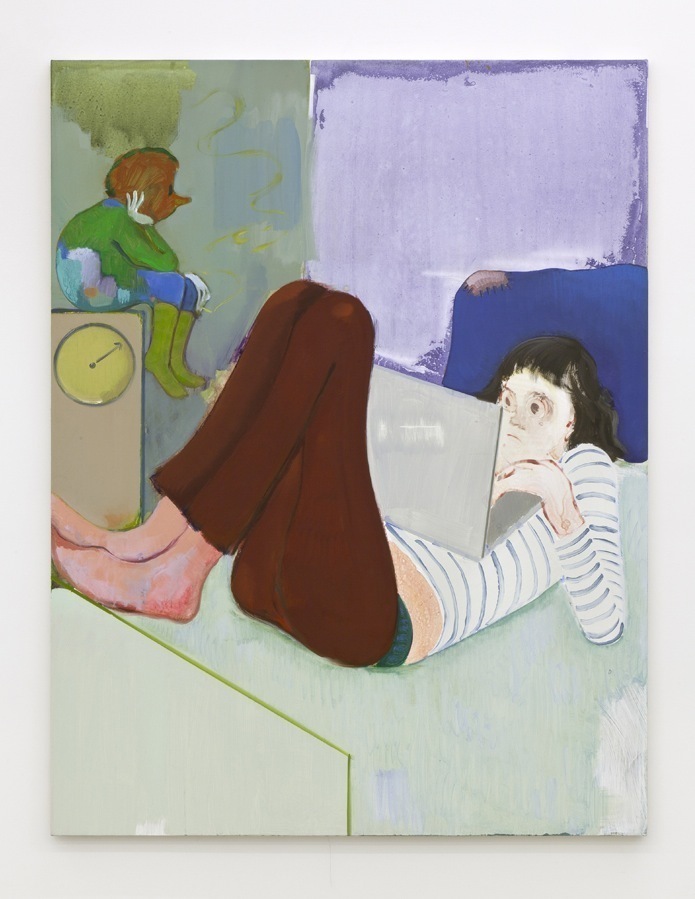

Left: Photo by Evert F. Baumgardner, via Wikimedia Commons; Right: Holly Andres, Calvin, 2006. Photo courtesy of Robert Mann Gallery.

Over the past century, rapid technological advances have revolutionized every aspect of the way we live and communicate. But while there’s been much discussion around technology’s impact on our attention spans, our workloads, and even the art world, less has been said about the physical impact it has had on the way we relate to the built environment.

Take, for example, the classic New York City tenement apartment. Built in the latter half of the 19th century, these dwellings, often just two rooms, were designed to house entire families of multiple generations. Now, these apartments are considered small for even a single individual.

Standards of living have certainly risen from tenement life, which was sometimes downright dangerous—helped in part by safety laws like The Tenement House Act of 1867, which required a shared toilet for every 20 residents in an attempt to codify regulations regarding sanitation, air flow, light, and access. But design also plays a role in this shift in occupancy expectations. The spaces in our apartments where a dining table and maybe even a piano and a bed once stood, are more often now fitted only with a sofa, a coffee table—and, most importantly, a TV.

With improved housing quality and the expansion of entertainment options, of our lives are increasingly spent inside the home. (The average American now spends more than 90 percent of their lives indoors or in a vehicle, according to The National Human Activity Pattern Survey in 2012). And we’re not just spending more time in our homes, we’re often spending those hours staring at screens of different sizes and functions—for the average American, more than 10 hours a day.

Visual entertainment wields an unseen influence over our relationship to physical space. As our preferred means of entertainment and the distance required to view it has changed, so too have our rooms and the furniture that fills them.

Photo of 1925 Radio, by Britt-Marie Sohlström, via Flickr.

1900: A Focus on Function

Before the advent of broadcast media, homes were organized around activities like eating and sleeping. As people migrated to cities for economic opportunity, many family members often squeezed into tenement-style apartments. Furniture came at a premium during this period preceding mass production, and it often took up little space and was focused on function. Toilets were shared and placed outside of the residences, which further increased the useable square footage within the home or apartment.

1920s–30s: Radio Comes Home

Following the introduction of broadcast radio by stations like Pittsburgh’s KDKA, which launched in 1920, the medium began to rise in popularity as a vehicle for news, sports, and serialized programing. Consumers began to create gathering areas in their homes centered around their new radios. But little space was required to enjoy them. It was possible for listeners to simply place a cabinet-style unit as a focal point of a room, or put a tabletop radio receiver, like Westinghouse’s early models, on a side table and enjoy the sound throughout the space.

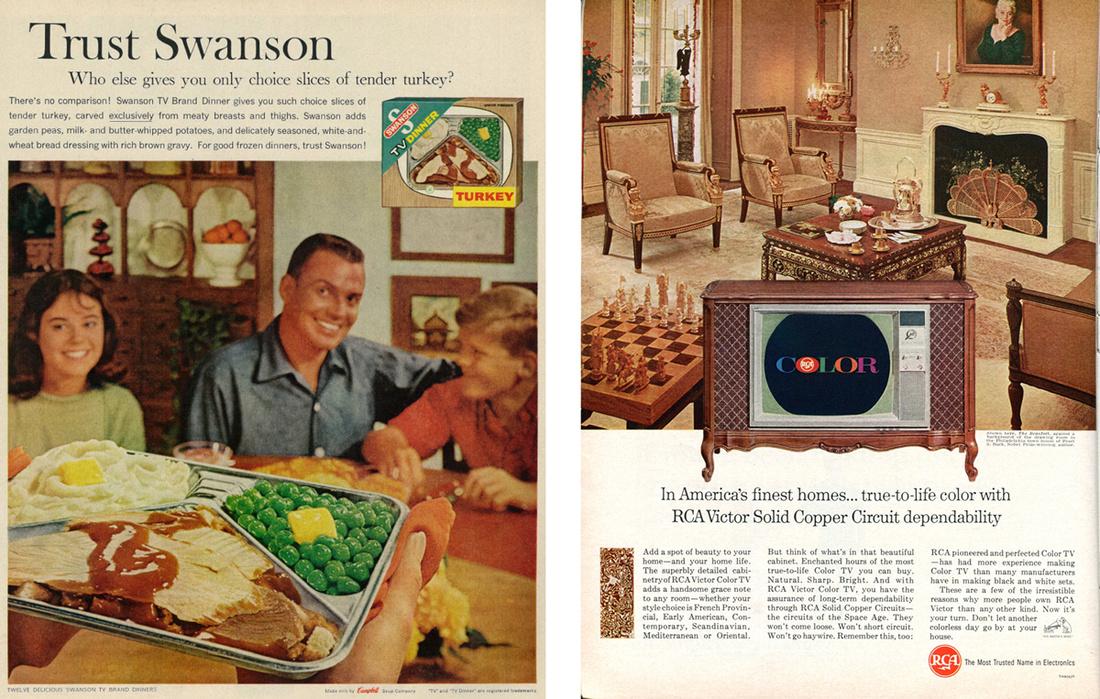

Left: 1961 Swanson Turkey TV Dinners Ad, “Trust Swanson,” published in Life magazine, April 14, 1961, Vol. 50 No. 15, via Flickr. Right: 1965 RCA Victor Color TV Advertisement Newsweek October 18, 1965, by SenseiAlan via Flickr.

Post-World War II: Television Takes Over America

A few fledgeling broadcast stations (including early versions of New York’s CBS and NBC) launched in the 1920s. But it was not until after World War II that TV hit the mainstream, when innovation met a rebounding economy. In 1946, there were about 6,000 televisions in the U.S., a fraction of the 40 million homes equipped with radios in the country. But by the middle of the 1950s, some 50 percent of American homes had a TV—despite the fact that in 1954 the early color 12.5-inch RCA CT-100 sold for $1,000, about $8,800 adjusted for inflation.Designed as furniture, the big, blocky wooden-encased sets with screens topping out around 11 inches became the centerpieces of family living areas, with sofas positioned across from them to enable viewing. One design side effect, though, was the TV tray, first created in the early 1950s—just in time for the invention of the Swanson TV Brand Frozen Dinner, created to be eaten as viewers tuned in to early classics like Howdy Doody.

1960s: TV Gets Gadgety

Innovations in plastic and an interest in space-age technology signaled television’s shift from a piece of furniture to a gadget. By this time, TVs had made their way into nearly 90 percent of American homes. Screens were more portable—and a modern design statement—with pieces like theAlgol 11 by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper from 1964. Viewers remained tethered to the broadcast schedule to catch programing. But by 1965, color television began making its way into the home, when NBC committed to the format for the majority of its shows.

Photo by Polygon Limited Realty, via Flickr.

1990s: Entertainment Gets Supersized

As television shows gave viewers a peek at the lifestyles of the rich and famous, Americans clamored for bigger sets—and more of them. New rear-projection, LCD, and plasma technology replaced the cathode ray tube, making the big-screen TV a possibility. These sets took up more room: a viewing distance between 8 and 16 feet was recommended for a standard-definition 40-inch set, as images were notoriously unclear at close range. With their required space and financial investment, these entertainment appliances turned into the focal point as dedicated media rooms became more popular in larger homes.

2000–2010s: Screens, Screens Everywhere

Televisions began to blend into the living room wall as smaller, thinner screens proliferated. Meanwhile, HDTV became the standard, reducing the recommended distance needed to view the picture by about half. But as technology developed, so did new competition for a viewer’s attention. By 2015, 71 percent of Americans reportedly slept with their smartphones. Cord-cutters began to spend more time with their phones and laptops, as streaming services like Netflix eliminated the reliance on a broadcast schedule. This turned viewing into a more personalized, individual experience—and for a small but growing number of Americans, it eliminated the need for a TV at all.

Today TV Takes a Stand

While curved screens, 4K Ultra HD, and organic light-emitting diode (OLED) technology make viewing a more immersive experience, designers are beginning to look at televisions as pieces of furniture again. Among the most talked about releases is the freestanding Samsung Serif by Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec, an elegant screen of up to 40 inches set within an I-beam-shaped frame.

The high-performance television set can sit directly on a surface, or thin legs can be attached for a standalone viewing experience. After decades of televisions intentionally receding from view, the Bouroullecs give the devices premium placement once again. The TV backs are even lined in fabric so that they can be enjoyed from 360 degrees in the middle of any room. Time will tell if this design-forward approach will get urbanites to reverse their trend of consuming programing on iPads and laptops rather than flatscreens.

—Heather Corcoran

No comments:

Post a Comment