French Art History in a Nutshell

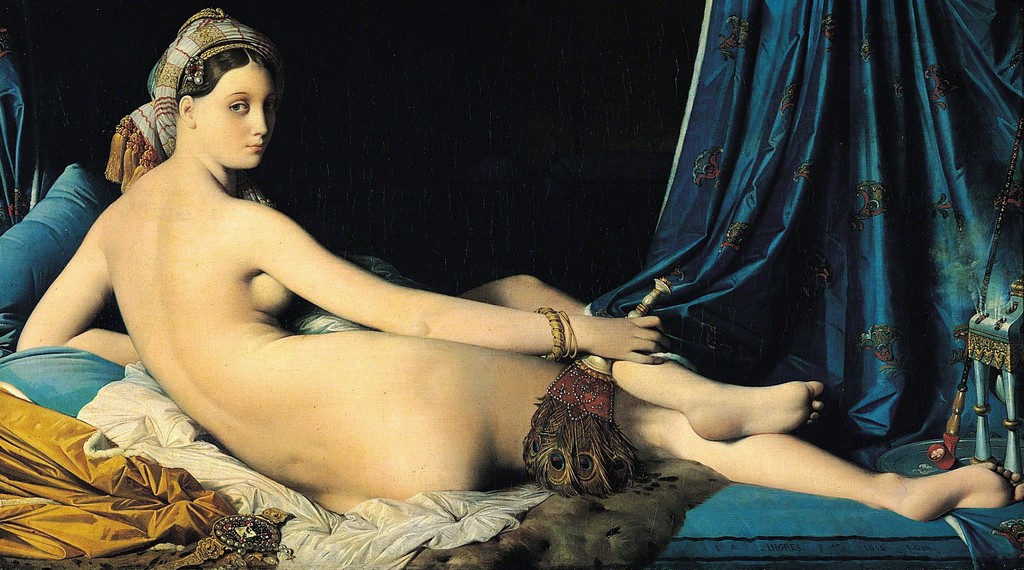

- La Grande Odalisque, 1814

French art in the popular imagination is often characterized by the dreamy, dauby landscapes of the Impressionists and the bolder, more vibrant work of 20th-century greats living la vie bohème in Paris. But still more of the genres that we associate with the art historical canon were pioneered in France. Pinpointing the very beginning of “French” art may prove an impossible task, but the region has been rich in creative expression since cave paintings were rendered at Lascaux an estimated 17,300 years ago, making them some of the earliest artistic traces in human history.

Fine art was finessed by the artists of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, an art school established in 1648 as an accessory of the French court. In 1699, the Academy mounted its first exhibition at the Louvre, where it continued to show for 100 years. From 1725 onwards, exhibitions were held in the Salon Carré, and became known simply as “salons.” The art presented in the salons dictated national and international tastes and formed the basis of what we have come to know today as traditional European art.

France’s story following the fall of Louis XVI in 1793 is one of revolution, and its art runs along that same axis. The Academy’s suspension, along with the dissolution of the court and its ultimate restructuring, destabilized the country’s artistic center. French artists responded to the atmosphere of social upheaval and growth with ceaseless innovation. Beginning with the undisputed master of Neoclassicism, Jacques-Louis David, through such ubiquitous art historical standouts as Gustave Courbet, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, and Louise Bourgeois, we present a capsule review of French art history from the 18th century to today.

Fine art was finessed by the artists of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, an art school established in 1648 as an accessory of the French court. In 1699, the Academy mounted its first exhibition at the Louvre, where it continued to show for 100 years. From 1725 onwards, exhibitions were held in the Salon Carré, and became known simply as “salons.” The art presented in the salons dictated national and international tastes and formed the basis of what we have come to know today as traditional European art.

France’s story following the fall of Louis XVI in 1793 is one of revolution, and its art runs along that same axis. The Academy’s suspension, along with the dissolution of the court and its ultimate restructuring, destabilized the country’s artistic center. French artists responded to the atmosphere of social upheaval and growth with ceaseless innovation. Beginning with the undisputed master of Neoclassicism, Jacques-Louis David, through such ubiquitous art historical standouts as Gustave Courbet, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, and Louise Bourgeois, we present a capsule review of French art history from the 18th century to today.

- Oath of the Horatii, 1784-1785

Obsession with the idealized forms and mythology of ancient Greek and Roman cultures made a comeback in fine art from the late-18th to the mid-19th century. As the Enlightenment took hold and revolution stirred, an emphasis on order and balance reigned supreme in the refined compositions produced by the artists of the Academy. The most prominent artist of the time was David, who painted both classical scenes—like masterpieces The Oath of the Horatii (1784-85) and The Intervention of the Sabine Women (1796-99)—and tableaus depicting the first revolution. His unfinished painting The Oath of the Tennis Court (1790-94) captured the chaotic enthusiasm of revolution and the somber Death of Marat (1793) showed the gruesome bathtub murder of the revolutionary leader. Later, David would create stately portraits of Napoléon and his court; as “First Painter to the Emperor,” his paintings became essential to the regime’s propaganda program.

Also of the era, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres trained under David and developed a unique style that often strayed from the precision of the Academy. Unlike his contemporaries, he depicted historical and physiological anomalies, such as in La Grande Odalisque (1814), his famous nude displaying an impossibly long back.

Also of the era, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres trained under David and developed a unique style that often strayed from the precision of the Academy. Unlike his contemporaries, he depicted historical and physiological anomalies, such as in La Grande Odalisque (1814), his famous nude displaying an impossibly long back.

- La Liberté guidant le peuple (Liberty Leading the People), 1830

Developing around the same period as Neoclassicism and stemming from the literature of the time, Romanticism took a more emotional, intimate approach to its subject matter, favoring contemporary and personal scenes over the historical or mythological tableaux of Neoclassicism. Imagination and the interior life of the self were guiding forces in works that often focused on nature and fantastical views of faraway lands. Théodore Géricault painted some of Romanticism’s best-known works, including the dramatic, devastating The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19), which captures a tragic shipwreck from 1816, heavily imbued with political critique. The painting earned Géricault a fair amount of infamy, as the events it depicted were already central to a national scandal regarding the reinstated monarchy.

A contemporary of Géricault, Eugene Delacroix portrayed historical subjects like the Neoclassicists, but his paintings were laden with emotional content and fiercely vibrant colors. Delacroix looked to the East for inspiration (a common fascination of the time that stemmed from France’s colonial activities), often painting foreign locales replete with bustling marketplaces and exotic animals. He also created what is perhaps the most iconic French image of all time: La Liberté guidant le peuple (1830) shows a disheveled but triumphant Liberty emerging from the violent mayhem of revolution while raising the tri-color flag.

A contemporary of Géricault, Eugene Delacroix portrayed historical subjects like the Neoclassicists, but his paintings were laden with emotional content and fiercely vibrant colors. Delacroix looked to the East for inspiration (a common fascination of the time that stemmed from France’s colonial activities), often painting foreign locales replete with bustling marketplaces and exotic animals. He also created what is perhaps the most iconic French image of all time: La Liberté guidant le peuple (1830) shows a disheveled but triumphant Liberty emerging from the violent mayhem of revolution while raising the tri-color flag.

- The Origin of the World, 1866Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- Iris, Messenger of the Gods (Figure in Flight), 1890/91

As the Revolution overturned France in the mid-19th century, a desire for egalitarianism began to inform artists’ work. Breaking away from the grandiose and emotionally charged subject matter of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, they focused their attention on everyday life and the common working men and women of France. Paintings of peasants toiling in the field, townspeople worshipping at church, or crowded city streets proliferated. In this climate, Gustave Courbet led the charge, painting forthright scenes of poverty and quotidian struggle, as well as unabashed views of sexuality, such as in his unflinching nude The Origin of the World (1866). Carrying elements of this genre into the next century, Auguste Rodin approached sculpture with an unusually realistic style. In bronze and marble, he forged bodies in motion and unidealized, conventional human forms along with centaurs and goddesses inspired by Classical mythology that connected back to his Neoclassical forebears.

- The Artist's Garden at Vétheuil, 1880

- Dancers at the Barre, ca. 1900

The late 19th century in French art belongs to the Impressionists, who were deemed radical for their loose brushwork and experimental approach to light and color that veered firmly away from realistic representation. Industry was booming across Western Europe, with technological advancements infiltrating daily life and increasing its pace. Characterized by loose “impressions” of scenes, this art explored the vagaries of visual perception and captured the new conditions of urban life. Impressionism in France was led by Monet, Renoir, Manet, Degas, Pissarro, Morisot, and Caillebotte, who painted everything from smudgy seascapes, gardens, farmlands, and picnics, to boisterous dancehalls, household interiors, and elegant flâneurs along city streets—all views of the emerging modern world, where industrial development opened up more time for leisure, be it in the countryside or rapidly expanding urban areas. Their work was initially derided in haute art society, before gaining traction and spreading to other countries.

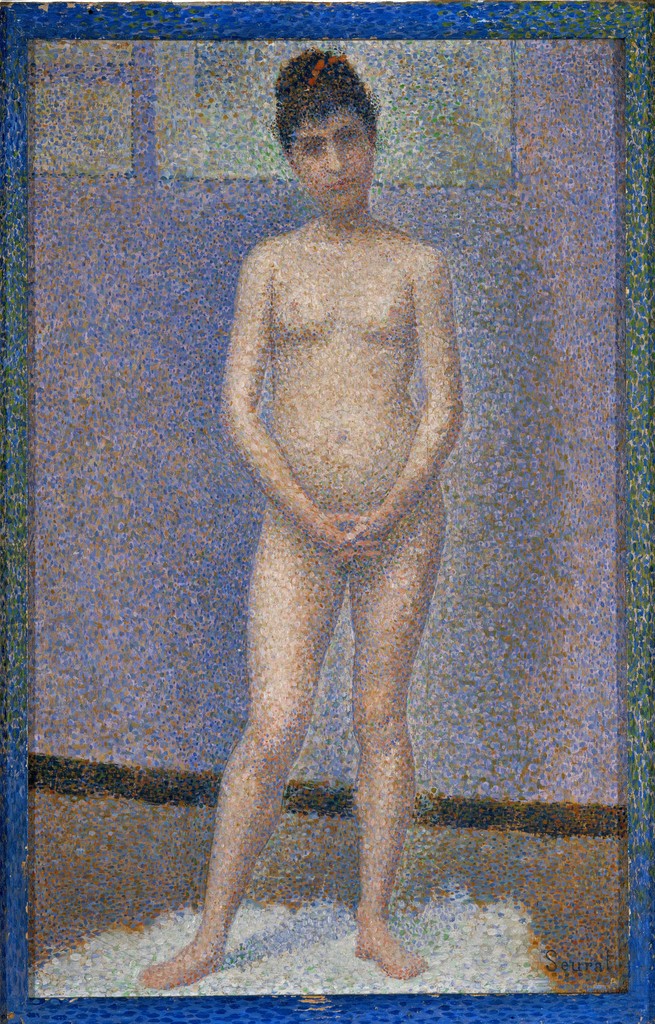

- Poseuse de face (Model, Front View), 1887Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- Contes Barbares (Primitive Tales), 1902

Focused more on expressing subjective experience, Post-Impressionism emerged towards the close of the 19th century and carried into the 20th, with French painters Cézanne, Gauguin, and Seurat at the helm (along with famed Dutchman Van Gogh). Each stepped out into their own style. Seurat is known for having pioneered Pointillism (complex images made from tiny dots of color), furthering the impulse of Impressionism to translate the mechanics of human perception. Gauguin’s striking scenes of Tahitian life were characterized by their Symbolism, which discarded scientific concerns for art that stemmed from individual emotional experience and notions of spirituality. Self-taught Henri Rousseau also painted bold, brightly colored scenes of exotic locales, but unlike Gauguin, Rousseau’s jungle landscapes were all imagined. Paul Signac extrapolated from Pointillism, printing airy, pastel lithographs with slightly larger flecks of color and light.

Inspired by Cézanne’s strong palette and style (as well as that of other Post-Impressionists), Fauvism became one of the earliest forms of modern art. Propelled by Matisse and Derain, the movement’s name derives from an early critique of their work, in which the painters were labeled fauves, or “wild beasts”—the vivid, clashing colors and flattened out, pattern-based images shocked the public, but paved the way for the Modernism of the next century.

Inspired by Cézanne’s strong palette and style (as well as that of other Post-Impressionists), Fauvism became one of the earliest forms of modern art. Propelled by Matisse and Derain, the movement’s name derives from an early critique of their work, in which the painters were labeled fauves, or “wild beasts”—the vivid, clashing colors and flattened out, pattern-based images shocked the public, but paved the way for the Modernism of the next century.

- Bicycle Wheel, 1963Private Collection of Richard Hamilton, Henley-on-Thames

- FEMME, ca. 1960Contact gallery

After Matisse and Derain helped fuel the modernist fires, French art expanded in a variety of directions. A cornerstone of the country’s avant-garde, Cubism—the fragmented, geometric twist on reality that pushed art into the conceptual—was driven by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and help to launch the cavalcade of experimental genres that followed. Avant-garde innovator Marcel Duchamp (known for pioneering the readymade) also dabbled in Cubism, as well as the Swiss movement Dadaism and, later, Surrealism. Penned by André Breton in 1924 and greatly influenced by the iconoclasm of the Dadaists, the Surrealist Manifesto called into being the otherworldly, mind-bending works of artists such as Yves Tanguy.

Sculptor Louise Bourgeois began her practice with similarly absurdist forms and notions, but gradually shifted her focus towards capturing instead the movement and psychology contained in her subjects. Another contemporary, Jean Dubuffet, fostered Art Brut (also known as Outsider Art), categorized as works created outside society’s influence, whether due to a lack of art education or the artist’s position on the margins of society. Europe’s response to the Abstract Expressionism blossoming after WWII in America was Art Informel, championed in part by French painters Pierre Soulages and Georges Mathieu. In the ’60s, Nouveau Réalisme was born, with elements of American Pop and Neo-Dada combined across an array of mediums; Yves Klein, Niki de Saint-Phalle, and Martial Raysse all participated.

Sculptor Louise Bourgeois began her practice with similarly absurdist forms and notions, but gradually shifted her focus towards capturing instead the movement and psychology contained in her subjects. Another contemporary, Jean Dubuffet, fostered Art Brut (also known as Outsider Art), categorized as works created outside society’s influence, whether due to a lack of art education or the artist’s position on the margins of society. Europe’s response to the Abstract Expressionism blossoming after WWII in America was Art Informel, championed in part by French painters Pierre Soulages and Georges Mathieu. In the ’60s, Nouveau Réalisme was born, with elements of American Pop and Neo-Dada combined across an array of mediums; Yves Klein, Niki de Saint-Phalle, and Martial Raysse all participated.

Contemporary

- The divorce, 1992Contact gallery

- De-extinction, 2014Contact gallery

French contemporary art is marked by traces of the past; while mediums and styles have evolved, a keen interest in the psychology of the self and the nature of existence and the world remain at its core. Notable artists of the later half of the 20th century and today include Christian Boltanski, who often works with found objects (in the readymade tradition of Duchamp); Sophie Calle, whose conceptual works feel deeply intimate; and Pierre Huyghe, whose multimedia practice sometimes incorporates living beings of all sorts (recent installations include a sculpture buzzing with a live bee colony in the MoMA’s garden and a fish tank rife with slinky, eel-like fish perched on the Met’s rooftop).

—Kate Haveles

No comments:

Post a Comment