|

BooksBaruch Spinoza and the Art of Thinking in Dangerous TimesThe philosopher was a champion of political and intellectual freedom, but he had no interest in being a martyr. Instead, he shows us how prudence and boldness can go hand in hand. By Adam Kirsch |

Books

Baruch Spinoza and the Art of Thinking in Dangerous Times

In March, 1668, Adriaan Koerbagh, a Dutch physician in his mid-thirties, hired Johannes Van Eede, a printer in Utrecht, to publish his new book, “A Light Shining in Dark Places, to Shed Light on Matters of Theology and Religion.” But Van Eede, after setting the first half of the manuscript, became uneasy about its highly unorthodox contents. Koerbagh argued that God is not a Trinity, as the Dutch Reformed Church taught, but an infinite and eternal substance that includes everything in existence. In his view, Jesus was just a human being, the Bible is not Holy Writ, and good and evil are merely terms we use for what benefits or harms us. The only reason people believe in the doctrine of Christianity, Koerbagh wrote, is that religious authorities “forbid people to investigate and order them to believe everything they say without examination, and they try to murder (if they do not escape) those who question things and thus arrive at knowledge and truth, as has happened many thousands of times.”

Now it was about to happen to Koerbagh himself. Van Eede, either outraged because of his religious beliefs or worried about his own legal liability, stopped work and turned over the manuscript to the sheriff of Utrecht, who in turn informed the sheriff of Amsterdam. Koerbagh was already well known to the authorities there; in February, they had seized all copies of his previous book, “A Flower Garden of All Sorts of Delights,” in which he had denied the existence of miracles and divine revelation. Realizing that he was in danger, Koerbagh went on the run, ending up in Leiden, where he disguised himself with a black wig. But a reward was offered and in July someone turned him in. Koerbagh was interrogated, tried, and sentenced to ten years in prison for blasphemy, to be followed by ten years of exile. The long sentence turned out to be unnecessary: he lasted just a year in prison before dying, in October, 1669.

A few months later, an even more subversive book was published in Amsterdam: “Tractatus Theologico-Politicus,” an anonymous Latin treatise that declared the best policy in religious matters to be “allowing every man to think what he likes, and say what he thinks.” In the preface, the author gave thanks for the “rare happiness of living in a republic, where everyone’s judgment is free and unshackled, where each may worship God as his conscience dictates, and where freedom is esteemed before all things dear and precious.” But the fact that the author withheld his name, and that the book’s Amsterdam publisher claimed on the title page that it had been printed in Hamburg, told another story. The author and the publisher were well aware that their unshackled judgment could put them in shackles.

Read our reviews of notable new fiction and nonfiction, updated every Wednesday.

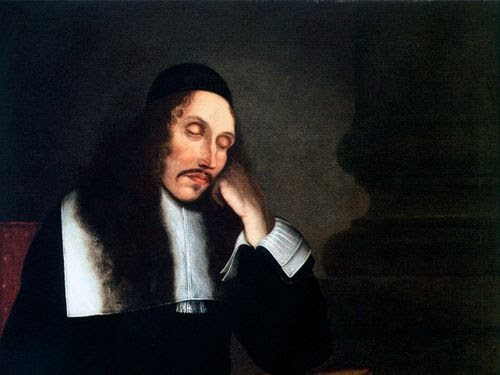

These feints couldn’t stop readers, or the authorities, from quickly figuring out that the “Tractatus” was the work of Baruch Spinoza. Although Spinoza, then in his late thirties, had previously published only one book, a guide to the fashionable philosophy of René Descartes, he was one of Amsterdam’s most notorious freethinkers. As a young man, he had been expelled from the city’s Jewish community for his heretical views on God and the Bible. (He published under the name Benedictus de Spinoza, Benedictus being the Latin equivalent of Baruch, which means “blessed” in Hebrew.) Living a quiet, solitary existence, supporting himself by grinding lenses for microscopes and telescopes, Spinoza developed his ideas into a comprehensive philosophical system, which he shared with a circle of friends in letters and conversations. When Koerbagh was interrogated, he was asked whether he had fallen under Spinoza’s malign influence. He acknowledged that they were friends, but insisted that they had never discussed ideas—even though what he wrote about God closely resembled what Spinoza had been saying for years.

Ministers in several cities immediately forbade booksellers to carry the “Tractatus,” and, in 1674, it was officially banned in the Netherlands, along with Thomas Hobbes’s “Leviathan.” Under the circumstances, Spinoza’s praise of Dutch freedom might well sound sarcastic. But the truth is that, compared with most of Europe in the seventeenth century, the Netherlands really was a haven of tolerance. In Spain or Italy, a book like Spinoza’s could get its author burned by the Inquisition; as it was, the attacks were aimed at his ideas, not his life. His praise of his country is better seen as a kind of appeal: Perhaps no country in Europe was truly free, but the Netherlands might be if it tried.

For Ian Buruma, a writer and historian and a former editor of The New York Review of Books, it is Spinoza’s dedication to freedom of thought—what he called libertas philosophandi—that makes him a thinker for our moment. In his new book, “Spinoza: Freedom’s Messiah,” a short biography in Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives series, Buruma observes that “intellectual freedom has once again become an important issue, even in countries, such as the United States, that pride themselves on being uniquely free.”

No American has to fear Adriaan Koerbagh’s fate, no matter how unpopular his or her opinions. Still, Buruma argues, “liberal thinking is being challenged from many sides where ideologies are increasingly entrenched, by bigoted reactionaries as well as by progressives who believe there can be no deviation from their chosen paths to justice.” And it is certainly true that, in the age of social media, informal pressure to toe a certain line can be as effective as legal threats. Offending the wrong people, even for a moment, can blow up the career of anyone from a Y.A. novelist to an Ivy League president.

In calling Spinoza a “messiah,” Buruma follows Heinrich Heine, the nineteenth-century German Jewish poet, who compared the philosopher to “his divine cousin, Jesus Christ. Like him, he suffered for his teachings. Like him, he wore the crown of thorns.” According to Jonathan Israel, a historian whose encyclopedic biography “Spinoza, Life and Legend” came out last year, “No other personage of his era came even close to being so decried, denounced and condemned in weighty texts of exhaustive length, over so long a span of time, in Latin, Dutch, French, English, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Hebrew, and other languages.”

Like deconstruction or critical race theory, “Spinozism

pinoza a “messiah,” Buruma follows Heinrich Heine, the

Like deconstruction or critical race theory, “Spinozism” became a popular target for many a moralist who could not have said exactly what it meant. Yet, although Spinoza was certainly a champion of political and intellectual freedom, he had no interest in being a martyr for them, and, if his life teaches anything about thinking in dangerous times, it is how prudence and boldness can go hand in hand. Not for nothing did he wear a ring inscribed with the Latin word “Caute”: “Be cautious.”

The boldest act of defiance in Spinoza’s life came at the beginning of his career as a philosopher, and made that career possible. In July, 1656, when he was twenty-three years old, Spinoza was cast out of Amsterdam’s Jewish community in a public ceremony. There are few contemporary sources for Spinoza’s early life, and it’s not known precisely what led to this rupture.

VIDEO FROM THE NEW YORKER

Knight of Fortune: Friendship Blooms at a Morgue

But the text of the ban, or herem, read aloud at a synagogue on Amsterdam’s Houtgracht canal, has been preserved, and it makes clear that what the community objected to was not any personal misdeed but Spinoza’s “evil opinions” and “abominable heresies,” which he refused to recant under pressure. For this reason, the leaders of the congregation declared, Spinoza “should be excommunicated and expelled from the people of Israel.” They invoked the fearsome punishment for disobedience laid down by Moses in the Book of Deuteronomy: “Cursed be he by day and cursed be he by night; cursed be he when he lies down and cursed be he when he rises up. Cursed be he when he goes out and cursed be he when he comes in.”

Spinoza wasn’t present to hear this curse read aloud, but he couldn’t escape its effects. The Jewish community into which he was born, in 1632, was uniquely close-knit, set off not only from the Dutch Christians around it but from other Jewish communities in Western Europe. Amsterdam’s Jews were descended from Portuguese conversos, Jews forcibly converted to Catholicism at the end of the fifteenth century, who continued to practice their faith in secret for generations. Spinoza’s parents and grandparents were among the many Portuguese Jews who moved to the Netherlands in the early seventeenth century, drawn by the promise of religious tolerance as well as commercial opportunities. Buruma, Dutch-born and Jewish on his mother’s side, notes that Spinoza and his brother were the first members of their family “in many generations to be born as a Jew, and not a crypto-Jew.”

Buruma writes that Spinoza’s excommunication was like being “ ‘canceled,’ as people might now say,” but this was a retribution that a Twitter mob could only dream of. Under the terms of the herem, all Jews, including Spinoza’s relatives, were forbidden to talk to or even go near him. He could no longer hope to live among the people he had known all his life, to do business with them, or to get married and start a family. The fact that Spinoza was willing to sacrifice everything for his right to think and speak freely shows how seriously he took libertas philosophandi, before he had published a word of philosophy.

Spinoza’s apostasy also makes him a key figure in modern Jewish history. He was hardly the first Jew to abandon Judaism, but he might have been the first to do so publicly without becoming a Christian or a Muslim. Instead, he fashioned a secular life, something that was hardly conceivable before the seventeenth century. In the “Tractatus,” he argued that, in a commercial state like the Netherlands, traditional religious identities no longer had any real meaning, anyway: “Matters have long since come to such a pass, that one can only pronounce a man Christian, Turk, Jew, or Heathen, by his general appearance and attire, by his frequenting this or that place of worship, or employing the phraseology of a particular sect—as for manner of life, it is in all cases the same.”

For members of later generations of European Jews hoping to emancipate themselves from religion, such as Heine and Sigmund Freud, this independence made Spinoza a role model. As Buruma writes, “He chose to think freely, and that made his tribal membership impossible.” Instead, Spinoza assembled his own tribe of like-minded individuals, most of them freethinking liberal Protestants. Israel and another eminent Spinoza biographer, Steven Nadler, have shed light on these key relationships. Franciscus van den Enden, Spinoza’s Latin teacher and sometime landlord, was a former Jesuit who drew up a plan for a utopian society in New Netherland, the Dutch colony that became New York; he ended up being hanged by the French for helping to hatch a plot against Louis XIV. Lodewijk Meyer, a leading figure in Dutch literary life, is believed to be the author of an anonymous book, published in 1666, that caused a huge scandal by arguing that the Bible should be analyzed critically and scientifically. Johannes Bouwmeester co-founded a club for freethinkers with the defiant name Nil Volentibus Arduum (“Nothing Is Difficult for the Willing”).

Spinoza assembled his own tribe of like-minded individuals, most of them freethinking liberal Protestants. Israel and another eminent Spinoza biographer, Steven Nadler, have shed light on these key relationships. Franciscus van den Enden, Spinoza’s Latin teacher and sometime landlord, was a former Jesuit who drew up a plan for a utopian society in New Netherland, the Dutch colony that became New York; he ended up being hanged by the French for helping to hatch a plot against Louis XIV. Lodewijk Meyer, a leading figure in Dutch literary life, is believed to be the author of an anonymous book, published in 1666, that caused a huge scandal by arguing that the Bible should be analyzed critically and scientifically. Johannes Bouwmeester co-founded a club for freethinkers with the defiant name Nil Volentibus Arduum (“Nothing Is Difficult for the Willing”).

Such figures helped to create what Israel calls the Radical Enlightenment, a tradition of political and religious thought that would transform the modern world. Democratic ideas that were punishable by imprisonment in the sixteen-sixties became the watchwords of the American and French Revolutions a century later. Today, the propositions about God and the Bible that sent Adriaan Koerbagh to prison are taken for granted by secular people around the world, especially in the Netherlands, where fifty-seven per cent of those fifteen years and older say they have no religion.

Many thinkers shared the ideas of the Radical Enlightenment, but it was Spinoza who forced Europe to reckon with them, by rooting them in a new philosophical system of formidable scope and rigor. When Spinoza writes that democracy is “of all forms of government the most natural, and the most consonant with individual liberty,” and that the best antidote to superstition is the study of science, “since the less men know of nature the more easily can they coin fictitious ideas,” he isn’t simply stating opinions. The title page of his magnum opus, the “Ethics,” promises that his ideas will be “ordine geometrico demonstrata,” “demonstrated in the manner of geometry,” and, like Euclid, he presents his arguments in the form of numbered axioms and propositions. Once you accept Spinoza’s basic assumptions about God and the universe, his political and social ideas are supposed to be as self-evident as the Pythagorean theorem.

At the center of Spinoza’s thought is a new way of understanding God. Indeed, his God was so different from the one worshipped in churches and synagogues that almost everyone who read him believed he was an atheist. But Spinoza indignantly rejected the charge of atheism, and nowhere in the “Ethics” does he deny the existence of God. What he denies is that God exists as a being or intelligence separate from the rest of the universe, as he is conceived of in Judaism and Christianity. Spinoza’s argument is disconcertingly simple. God is “a being absolutely infinite,” and the idea of infinity “involves no negation”: it would be contradictory to say that there is some quality an infinite being does not possess or some space it does not occupy. It is therefore impossible for God to be somewhere—up in Heaven, perhaps—but not here, where we are. If God exists, then he must be absolutely everywhere; not even our own bodies and minds can be separate from him. As Proposition XV of the “Ethics” famously states, “Whatsoever is, is in God, and without God nothing can be, or be conceived.”

This idea is known as pantheism, from the Greek for “all” and “God.” One way of looking at pantheism is that it brings us closer to God than conventional religious belief ever could; in the nineteenth century, Romantic writers considered Spinoza a “God-intoxicated man.” But, if there is no difference or distance between God and the rest of the universe, then he cannot do any of the things that we ordinarily think of God as doing: hearing prayers, working miracles, creating the world with a “Let there be light.” Really, there is no compelling reason to call Spinoza’s infinite substance God in the first place. We might as well call it Being, or Everything, or Nature. In Part IV of the “Ethics,” Spinoza refers to “the eternal and infinite Being, which we call God or Nature”—in Latin, Deus sive natura.

In closing the gap between humanity, God, and nature, Spinoza also does away with any space for free will. The infinite substance that is God appears to be constantly changing, yet always in accordance with what Spinoza calls “the necessity of his nature,” or what a scientist would call natural laws. The ancient Greek engineer Archimedes said that with a lever and a place to stand he could move the Earth, but in Spinoza’s universe there is no place outside nature where we can stand in order to exert force on it, since we ourselves are part of nature.

This might sound like a fatalistic view of the world, and for later thinkers the idea that the universe is nothing but a mechanism in motion, constantly changing but never going anywhere, was a recipe for nihilism and despair. But one of the things that draws people to Spinoza, and makes him perhaps the most beloved philosopher since Socrates, is his confident equanimity. He argues that the highest happiness of which human beings are capable is seeing the universe “under the aspect of eternity,” which means understanding that everything is as it must be. When he writes that “blessedness is nothing else but the contentment of spirit, which arises from the intuitive knowledge of God,” he might sound like a mystic, but for him knowing God is not a supernatural experience but a rational one. It simply means knowing “the actions which follow from the necessity of his nature,” in the same way that knowing the law of gravity allows us to understand why an object thrown with a certain force will follow a certain trajectory.

It is because Spinoza sees true understanding as the key to happiness that he insists on freedom of thought. When religious authorities tell people what to believe, they make it harder to achieve a correct idea of God, and thus block the road to blessedness. Spinoza advocated for democratic government because he thought that it was more likely than monarchy or aristocracy to preserve libertas philosophandi, and thus to make it possible for human beings to become happy. As he writes in the “Tractatus,” “The basis and aim of a democracy is to avoid the desires as irrational, and to bring men as far as possible under the control of reason, so that they may live in peace and harmony.”

Clearly, this is not a description of the society we live in today. Liberal democracy as we know it rests on a certain intuition about equality: if all people are created equal, then no one has a monopoly on truth or wisdom, so no one has the right to dictate to others without their consent. This makes democracy a recipe for constant disagreement, as individuals and groups argue their way to some kind of acceptable consensus.

This was not the way Spinoza thought about freedom. He believed that there was one truth, which he understood and most people did not, and his experiences with religion and politics left him with no illusions about the wisdom of the crowd. Buruma, who excels at setting a rather unworldly man in the public life of his time, describes how, in 1672, a mob in The Hague lynched Johan and Cornelis de Witt, brothers who had led the Netherlands’ liberal regime during what is now remembered as the Dutch Golden Age. “One man tried to bite off Cornelis’s testicles,” Buruma writes. “Women danced in a frenzy after wrapping themselves in the slippery intestines.” Spinoza, who was living “only a short walk away,” wept at the news and had to be physically restrained from going to the site of the massacre to set up a placard reading “Ultimi barbarorum,” “the lowest of barbarians.”

As a freethinker who had run afoul of both Judaism and Christianity, Spinoza knew that bigotry and fanaticism weren’t just imposed on the people; they were also imposed by the people. Part of the reason he never met a fate like Koerbagh’s is that he took care not to provoke the crowd. Koerbagh wrote his books in Dutch so that anyone could read them, but Spinoza stuck to Latin, the language of the learned élite. In the preface to the “Tractatus,” he declares that he is writing only for philosophers and discourages “the multitude, and those of like passions with the multitude,” from reading the book: “I would rather that they should utterly neglect it, than that they should misinterpret it after their wont.”

When the “Tractatus” provoked a hostile reaction anyway, Spinoza decided not to publish anything else. He also turned down an offer to become a professor at the University of Heidelberg, on the ground that holding an official position would expose him to even more attacks. All of his work, including the “Ethics,” was left in manuscript form for his friends to print after his death. He died relatively young, in 1677, at the age of forty-four, of a lung condition that may have been linked to glass particles inhaled while grinding lenses.

To Leo Strauss, one of Spinoza’s most influential twentieth-century interpreters, this caution put him in a long philosophical tradition. In 1941, Strauss, who had fled Nazi Germany and was teaching with other Jewish refugees at the New School, in New York, published an essay titled “Persecution and the Art of Writing,” in which he argued that the repression and censorship then reigning in totalitarian Europe represented a return to the historical norm. Ever since Socrates was put to death by the Athenian assembly, philosophers had known that it was dangerous to speak the whole truth in public. When it comes to politics and religion, Strauss wrote, “a man of independent thought can utter his views in public and remain unharmed, provided he moves with circumspection. He can even utter them in print without incurring any danger, provided he is capable of writing between the lines.”

Strauss considered Spinoza a classic example of this “esoteric” style of writing, noting that the “Caute” on his ring referred to “the caution that the philosopher needs in his intercourse with non-philosophers.” If, as Buruma warns, we are entering an era in which “freedom of thought is under threat from secular theologies,” Spinoza may be the role model we need: a thinker who spoke the most outrageous truths he knew, and still managed to die in his bed. ♦

No comments:

Post a Comment