SALZBURG.- A new thematic presentation showcasing the rich collections of the

Museum der Moderne Salzburg is being staged on level [2] at Mönchsberg. The selected works complement each other perfectly and, in addition to pieces from the museum’s own holdings, have been compiled from the following collections: Generali Foundation Collection—Permanent Loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, the Austrian Federal Photography Collection, and the Bank Austria FOTOGRAFIS Collection. The exhibition includes recent acquisitions as well as a room dedicated to the art of Gustav Metzger, the founder of Auto-Destructive art, who recently died at the age of ninety.

The invention of the photographic and film camera opened up new opportunities to record and reflect movement in art. Technological innovations vastly increased artists’ expressive possibilities, although to this day, classic techniques such as drawing continue to be used as a way of perceiving and representing movement. “Artists’ exploration of movement— and of forms of its depiction—also questions the limits and preconditions of the respective (often new) medium. It reflects constants in art, such as the perception of subjects and objects, the factors of space and time, and the role of the viewer within this framework,” says Sabine Breitwieser, Director of the Museum der Moderne Salzburg. “The terms ‘photo’ and ‘kinetics’ come from the Greek words for light and movement. In the 1950s in particular, these two components played an important part in the development of Kinetic art, setting images, objects, or the human body in motion,” Antonia Lotz, Curator of the Generali Foundation Collection explains. The selection of works focuses on various aspects of movement, comprising art forms generally regarded as static—such as drawing, painting, and photography— and moving objects, performance, and film. The exhibition features over one hundred works by approximately thirty artists from nine different countries.

Thematic tour of the exhibition

Dorit Margreiter’s art sets the stage for the exhibition’s theme: Margreiter’s work zentrum (cinéma) (2016) combines the utopia of design and typography with the idea of the mobile, an art object that takes on ever-new forms through constant motion. Responding to currents of air, this freefloating kinetic object is held in balance between stillness and movement while also allowing the viewer to become part of the pictorial space. Margreiter’s series of “light drawings” uses sunlight to capture traces of forms on paper, for which she employs the same letters that compose the word “cinéma” in the mobile. These techniques, and the resulting abstractions, recall photograms in the tradition of Bauhaus and Constructivism.

The theme of artists working with light is continued with a wall dedicated to photograms and photographs. One of the milestones in photographic and film history was the serial photography invented by Eadweard Muybridge, for the first time capturing sequences of humans and animals in movement. The photogram, which was invented along with photography, involves arranging objects on light-sensitive material, which is then exposed to light, producing silhouetted images in white on a black background without the use of a camera. In the early years of photographic art, this technique was continually being rediscovered, with Christian Schad, with his “Schadographs,” and Man Ray, with his “rayographs,” among its inventors. László Moholy-Nagy also used this method and in the 1920s made a major contribution to establishing this new art form. Lotte Jacobi’s work likewise includes camera-less photographs. In her “photogenics” from the 1950s, she used small pieces of glass or twisted cellophane to interrupt beams of light shining onto photographic paper. Interest in the photogram continued through to Barbara Kasten’s works from the late 1970s and on to the present day, represented by an artwork created with light by Ernst Caramelle as well as Werner Kaligofsky’s “Adgraphics.” Finally, photographs by Francis Bruguière, Jaromír Funke, Heinz Loew, and Otto Steinert are included as examples of photographic still lifes using light and shadow, various studies of light and movement, as well as experiments using double- and long-exposure photography.

The light objects by Brigitte Kowanz translate the relationship of light and shadow into three-dimensional space. Kowanz, who is representing Austria at the Venice Biennale this year, discovered light as her main artistic medium early on. She first started out by going beyond the conventional concept of the picture and of painting, later also beyond the object, aiming to balance the relationship between work, space, and viewer. The restructuring of the relationship of viewer and work was a key theme for various art movements in the 1960s, and especially for Kinetic art. Marc Adrian integrated movement as an optical illusion in his reverse-glass montages, impelling viewers to walk up and down in front of the images or move their heads from side to side. Alfons Schilling, too, was interested in the depiction of space and movement in a wide variety of media. In his lenticular photographs, composed of up to three images, certain elements can only be grasped if the viewer remains in constant motion before the picture.

Another group of works examines the moving body in performance and dance in the context of the conflicting forces of politics and history. The choreographer and dancer Simone Forti, who describes herself as a “movement artist,” captured her famous performance Huddle (1961) in a hologram, into which movement is reintroduced by the audience walking around it. Helene von Taussig’s drawn studies conjure up the illusion of sequences of movement by the expressionist dancer Harald Kreutzberg, reminiscent, in their entirety, of a flip book. Harald Kreutzberg, one of Germany’s most important Ausdruckstanz (expressive dance) artists, was able to continue his career in Nazi Germany without interruption. In contrast to other modern art forms, Ausdruckstanz was not classified as “degenerate” but was actively promoted as “German Dance.” The relationship between dance, ideology, and politics is also the subject of the video installation Truly Spun Never (2016) by Andrea Geyer. The work was commissioned by the Museum der Moderne Salzburg for the exhibition Art—Music—Dance and has recently been added to the permanent collection. Works by Marko Lulić and Luiza Margan also address National Socialist history. Lulić refers to Bogdan Bogdanović’s monument at the Jasenovac anti-fascist memorial in Croatia, juxtaposing this with the choreographed bodies of a group of dancers engaging in a dialogue with the concrete sculpture. Luiza Margan uses her own body to extend photos of a partisan memorial in Croatia beyond the image and into reality.

Depicting movement in paintings, drawings, and photographs was a focus in the work of several artists. A prominent example is Erika Giovanna Klien, who was an exponent of Kineticism, a specifically Viennese art movement between the years 1919 and 1929. Her portfolio of twelve linocuts explores the movement of humans, animals, plants, and light. It is based on her experience of Franz Čižek’s teachings at Vienna’s Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts), where Kineticism emerged out of exploring the forms of Cubism and the movement and rhythms in Futurism. Rediscoveries in the museum’s own collection include graphic works by Max Ernst that are dedicated to rhythm and dance with a Surrealist slant. Surrealism and Fantastic Realism were the starting point for Vienna-born artist Curt Stenvert, who, from 1946, was preoccupied with the origins, impetus, and motivation behind movement. Stenvert, who also explored the representation of music through the painted, dynamic line in his works, was one of the founder members of the legendary Art Club that would meet during the 1950s at the venue Strohkoffer in the cellar underneath Adolf Loos’s American Bar in Vienna. In his photo series Art Club, Strohkoffer, Ferry Radax used multiple exposure to capture the vibrant Viennese art and jazz scene. An interest in music also resonates in the series of Etudes by Ulrike Lienbacher. In a second series of works, called Constellations, Lienbacher researches movement through drawings. The different-sized sheets express the ephemeral character of dance and are also some of the Museum der Moderne Salzburg’s most recent acquisitions, following last year’s exhibition Art—Music—Dance. Ian Wallace’s photo series conceals a choreography reminiscent of performance and contemporary dance. The artist aimed to create an abstract composition through the arrangement of people. The resulting tension between abstraction and figuration characterizes many of the works brought together in this exhibition.

The slide installation 1991 by Mathias Poledna / Karthik Pandian is based on a 35mm film, recorded on a camera rotated at a 90-degree angle to produce a high-resolution, vertical-format portrait of the model Marike Le Roux. The twenty-four frames per second of film have each been framed as a slide, thus dismantling the film into its component parts. The artists then slow the film down even further by showing only one slide per day, the minimal changes are therefore only perceivable through repeated visits to the exhibition.

In memory of the artist Gustav Metzger (1926–2017), who died in March 2017, one room of the exhibition has been dedicated to his work. In 1959, Metzger devised his concept of Auto-Destructive Art, in which works destroy themselves through biological, chemical, or technological systems, only becoming complete as an artwork once this disintegrative process has finished. Metzger co-organized the Destruction in Art Symposium in London in 1966, a key international event examining the theme of destruction from the perspective of the post-war generation of artists. His work Mobbile (1970) adds natural ingredients to a kinetic sculpture: tree branches and pieces of meat are suspended in an acrylic glass cube on a car roof, with a tube connecting it to the car’s exhaust pipe. As the contents deteriorate, the automobile becomes a “mobile destroyer.”

With works by Marc Adrian (1930 – 2008 Vienna, AT), Francis Bruguière (1879 San Francisco, CA, US – 1945 London, GB), Ernst Caramelle (1952 Hall, AT – Frankfurt am Main, DE and New York, NY, US), Max Ernst (1891 Brühl, DE – 1976 Paris, FR), Simone Forti (1935 Florence, IT – Los Angeles, CA, US), Jaromír Funke (1896 Skuteč, CZ – 1945 Kolín, CZ), Andrea Geyer (1971 Freiburg, DE – New York, NY, US), Lotte Jacobi (1896 Toruń, PL – 1990 Deering, NH, US), Werner Kaligofsky (1957 Wörgl, AT – Vienna, AT), Barbara Kasten (1936 Chicago, IL, US), Erika Giovanna Klien (1900 Borgo Valsugana, IT – 1957 New York, NY, US), Brigitte Kowanz (1957 Vienna, AT), Ulrike Lienbacher (1963 Oberndorf / Salzburg – Salzburg and Vienna, AT), Heinz Loew (1903 Leipzig, DE – 1981 London, GB), Marko Lulić (1972 Vienna, AT), Luiza Margan (1983, Rijeka, HR – Vienna, AT), Dorit Margreiter (1967 Vienna, AT), Gustav Metzger (1926 Nuremberg, DE – 2017 London, GB), László Moholy-Nagy (1895 Bácsborsód, HU – 1946 Chicago, IL, US), Eadweard Muybridge (1830 – 1904 Kingston upon Thames, GB), Mathias Poledna / Karthik Pandian (1965 Vienna, AT – Los Angeles, CA, US / 1981 Los Angeles, CA, US), Ferry Radax (1932 Vienna, AT), Man Ray (1890 Philadelphia, PA, US – 1976 Paris, FR), Christian Schad (1894 Miesbach, DE – 1982 Stuttgart, DE), Alfons Schilling (1934 Basel, CH – 2013 Vienna, AT), Otto Steinert (1915 Saarbrücken, DE – 1978 Essen, DE), Curt Stenvert (1920 Vienna, AT – 1992 Cologne, DE), Helene von Taussig (1879 Vienna, AT – 1942 Ghetto Izbica, PL), Ian Wallace (1943 Shoreham, GB – Vancouver, CA)

Curated by: Antonia Lotz, Curator of the Generali Foundation Collection, under the leadership of Sabine Breitwieser, Director of the Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Man Ray, Rayogramm, 1922–1926. Gelatin silver print after rayograph (print 1966–1972) Museum der Moderne Salzburg—FOTOGRAFIS Bank Austria Collection © Museum der Moderne Salzburg / Bildrecht, Vienna, 2017, Photo: Rainer Iglar.

Man Ray, Rayogramm, 1922–1926. Gelatin silver print after rayograph (print 1966–1972) Museum der Moderne Salzburg—FOTOGRAFIS Bank Austria Collection © Museum der Moderne Salzburg / Bildrecht, Vienna, 2017, Photo: Rainer Iglar.

Masterpiece, 1962

Masterpiece, 1962 Girl With Ball, 1961

Girl With Ball, 1961 Nudes With Beach Ball, 1992

Nudes With Beach Ball, 1992 Night Seascape, 1977

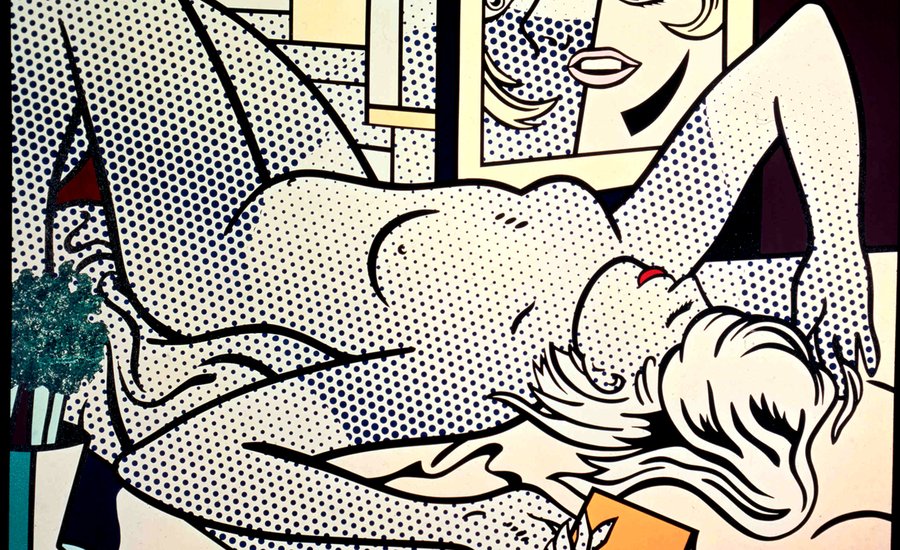

Night Seascape, 1977 Nude With Abstract Painting, 1994

Nude With Abstract Painting, 1994 'Whaam!', 1963

'Whaam!', 1963 Mustard on White, 1963

Mustard on White, 1963 The Ring (Engagement), 1961-62

The Ring (Engagement), 1961-62 Shipboard Girl, 1965

Shipboard Girl, 1965 Bedroom at Arles, 1995

Bedroom at Arles, 1995 M-Maybe, 1965

M-Maybe, 1965 Aloha, 1962

Aloha, 1962 Kiss V, 1964

Kiss V, 1964 Forget It, Forget Me, 1962

Forget It, Forget Me, 1962 Reflections: Art, 1988

Reflections: Art, 1988 In the Car, 1965

In the Car, 1965 Thinking of Him, 1963

Thinking of Him, 1963 Head With Blue Shadow, 1965

Head With Blue Shadow, 1965 Sunrise, 1965

Sunrise, 1965