Art Market

Artists Who Donate Work to Benefit Auctions Get Little More Than Good Karma

The founders of Miss Porter’s School, an all-girls high school located in Farmington, Connecticut, believed a stellar education can open a new world of opportunity for girls. To support this mission, a group of collectors and female artists came together to back what is being billed as the first-ever benefit auction of works exclusively by women, which is taking place March 1st at Sotheby’s in New York. Sale proceeds will go towards providing financial aid so that an even more diverse student body can attend Miss Porter’s School.

The generosity of these artists and others who have contributed works to the sale is inspiring under any circumstances. It is particularly notable because of the negligible tax benefits they will receive for their gifts. Contrary to public perception, donors who contribute works to charity auctions are driven by passion, not tax relief. This is especially true for artists who donate their own work.

A benefit for tomorrow’s women

Established in 1843, Miss Porter’s School was founded with the radical aim of providing young women with the same high-school education as their male peers. The school’s curriculum included a full panoply of science, language, and mathematics courses, in addition to various athletic opportunities. Today, the school has 312 students, most of whom live on campus as boarders. Around one-third of the students receive some form of financial aid to help them attend the school.

The idea for a benefit auction started in the summer of 2016, as planning began to honor the 175th anniversary of the school’s founding. A small leadership team came together to brainstorm auction concepts. The team was initially comprised of Dr. Anna Swinbourne, a former Museum of Modern Art curator who now teaches at Miss Porter’s, and Dr. Sunnie Evers, a school alumnus and trustee; they were then joined by Agnes Gund, the noted philanthropist, MoMA trustee, and Miss Porter’s alumnus.

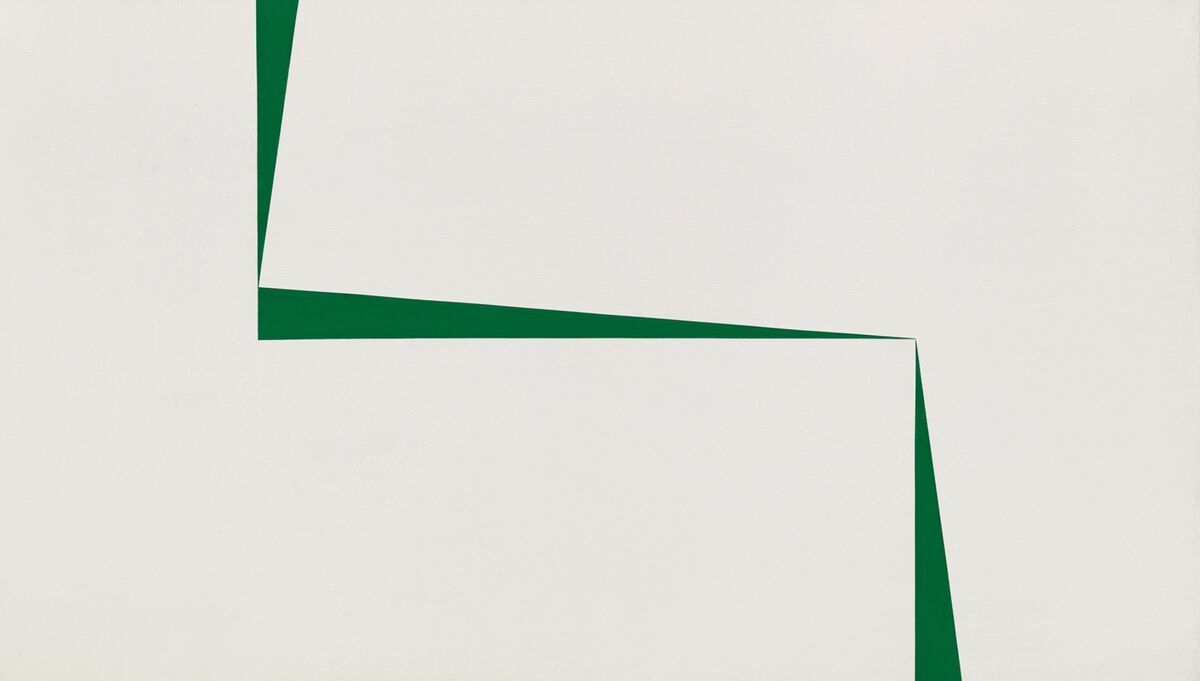

Carmen Herrera, Blanco y Verde, 1966–67. Courtesy of Sothebys.

The team quickly coalesced around two ideas: The auction should only include work by women artists, and all sale proceeds should go towards financial aid. They then invited artists, collectors, gallerists, and others to turn the concept into a reality. Most of the artworks and support have come from contributors who believe in the power of single-sex education for women, even if they are not alumni of Miss Porter’s: Oprah Winfrey, a longtime supporter of single-sex education, is an honorary co-chair of the auction, alongside Gund.

Titled “By Women, for Tomorrow’s Women,” the live and online auctions have 40 works by 38 artists. The objects range in value from approximately $1,000 to $1.5 million, including pieces by

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

. The most valuable work in the sale is an early painting by Herrera, exhibited as part of her 2016 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which was donated by Gund. Around two-thirds of the works in the sale were donated by artists themselves.

The generosity of artists

These artists are generous in the extreme: None of them will receive meaningful tax benefits from their donations, due to two U.S. tax code provisions.

When a taxpayer donates an artwork to a charitable organization, she can receive a charitable deduction equal to the fair market value of the object only if the organization receiving it passes what is called the “related use” test. Put simply, the organization must use the donated artwork in pursuit of its mission. Art that is accepted into the permanent collection of a museum passes this test, as does art donated to a school where it will be displayed and used in art history classes. But if the intent of the charity is to sell the work, then the donation fails the “related use” test. In these circumstances, the taxpayer will only be able to receive a charitable deduction equal to what the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) calls their “basis” in the object, which is typically much lower than its fair market value. Because all of the artworks donated to the Miss Porter’s auction do not meet the “related use” test, it’s essential to understand how the IRS defines “basis.”

4 Images

View Slideshow

The IRS defines “basis” very differently for artists and collectors. Artists can only deduct what it cost them to make the artwork. For example, if an artist donated a drawing with a $100,000 fair market value to a benefit auction, they would likely receive a tax deduction of around $100 for it—the cost of the pencils and paper that went into making it. This is true even if the work sells for $100,000 or more in the auction.

So all the artists donating their works to the Miss Porter’s auction are receiving essentially no tax benefits for their generosity. Collectors are marginally better off than the artists, because the IRS deems their basis to be what they originally spent to buy the artwork. For the kinds of works that show up at auction, that is still likely to be far less than a work’s current fair market value. With that in mind, hats off to the great collectors, gallerists, and especially artists whose substantial generosity will bring more opportunities to a new, diverse generation of Miss Porter’s students.

Doug Woodham is Managing Partner of Art Fiduciary Advisors, former President of Christie’s for the Americas, and author of Art Collecting Today: Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art.