Articles

Visiting the Museum of Modern Art at Sunrise

For those who wake up hungry for art, the Museum of Modern Art is opening its doors at 7:30am every Wednesday in October.

At 7:15am on a Wednesday morning, it occurs to me I’ve never seen the gates open at the Museum of Modern Art before. I am here, with a very obliging friend, for Quiet Mornings,

the museum’s program to open its fourth and fifth floors at 7:30am for

reduced admission every Wednesday in October (a partnership with culture

website Flavorpill). There is an optional meditation session from

8:30am to 9am, and then the museum closes until its regular opening time

of 10:30am.

The smattering of people outside the building is

comprised of more city dwellers than tourists; perhaps these locals are

seeking a break from their usual pre-work routine of coffee and a bagel.

Inside, a wealth of cushions and folding stools are set up on the floor

of the lobby for the meditation later. I remember going to MoMA a few

years ago in hopes of seeing an exhibition and having to wade through

floods of aimless visitors to reach it; this is not the case today. My

friend and I slowly make our way through the fourth floor galleries

showcasing work from the 1960s. It amuses me to enter the first room on

this Quiet Morning and be greeted with the periodic shrieks of John

Whitney’s 1961 video of revolving, brightly colored shapes, “Catalog,” but otherwise MoMA is very quiet. I admire sculptures like Yayoi Kusama’s “Accumulation No. 1” (1962) and Claes Oldenburg’s “Floor Cone” of the same year. Their curving shapes are comforting as the clock approaches 8am.

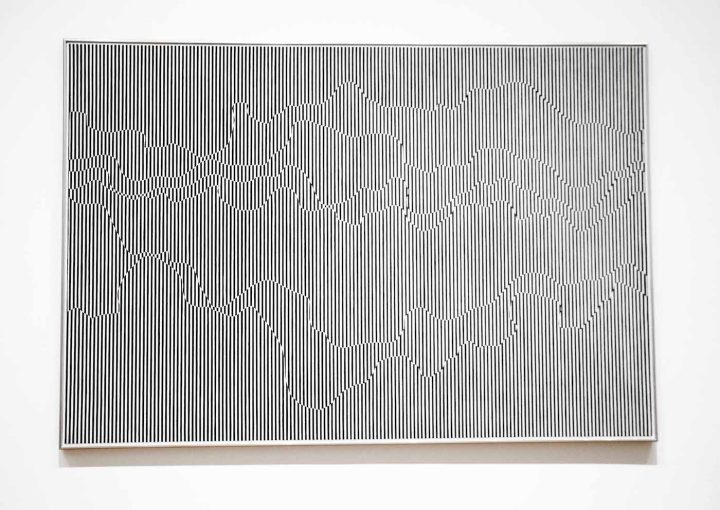

My friend and I come upon Julian Stanczak’s 1963 painting “The Duel,”

an Op art composition in black and white with lines popping

simultaneously toward and away from the eye. “I can’t take this picture

this early in the morning,” my friend says, walking away. While I feel

energized by this particular work, I begin to echo his sentiment as I

approach Paul Thek’s “Hippopotamus Poison” (1965), a wax sculpture meant to evoke rotting meat, and a video of Carolee Schneemann’s 1964 performance piece “Meat Joy,”

in which a series of mostly nude couples writhe together, slapping each

other with various meats and dead fish. Yes, it is much too early for

this, I think.

I am reinvigorated as I enter the 1967 gallery, where

Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” plays in the background. It’s not

too early for Grace Slick, I think as I peruse the museum’s wall of

neon-colored concert posters from the era. It’s only when I enter the

adjacent gallery filled with 1960s furniture that I realize the sun has

begun to shine outside. Since many of the galleries are shielded from

exterior light, this Quiet Morning at times doesn’t feel like morning at

all, doesn’t feel too different from visiting the museum at any other

time of day — save for the unrelenting caffeine deprivation addling my

brain and eyelids.

At 8:30am we make our way downstairs to the cushions

and stools now filled with people. The lobby is brimming with sunlight

and a guided meditation, led by expert Biet Simkin, begins. She purrs

instructions and the entire crowd shuts its eyes. While I, neurotic

writer that I am, am not often prone to a meaningful pause in mental

activity, my blood begins to buzz, vibrating in response to the

sinuousness of her voice. For once, I don’t think of anything except how

much I love this feeling pulsing through my veins. When the meditation

ends, Biet releases us into the October morning with wishes of positive

energy and self-reflection.

My friend begins chatting to me as we leave MoMA, but

for a while I can’t respond, and don’t want to. I just want to feel my

blood and hear the honk of taxicabs, the roll of tires across pavement,

the buzz of the New York morning.

The final Quiet Mornings event takes place Wednesday, October 26 at 7:30am at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Midtown, Manhattan).