Art

5 Must-See Shows at Blue-Chip Galleries You Can View Online

Frida Orupabo, installation view of “12 self portraits” at Sant’Andrea de Scaphis, 2020. Photo by Roberto Apa. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York/Rome.

While galleries have temporarily closed worldwide due to COVID-19, we can still be inspired by the work of contemporary artists. As part of Artsy’s Art Keeps Going campaign, we’re exploring shows that have been impacted by art spaces going dark. Every week, we’re featuring five exhibitions that you can access via Artsy, with insights from the artists and our writers. This week, we’re sharing a selection of fresh work at blue-chip galleries from Rome to Mexico City.

David Zwirner, New York

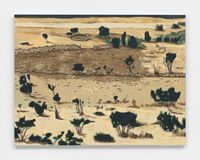

Mamma Andersson, installation view of “The Lost Paradise” at David Zwirner, New York, 2020. Courtesy of David Zwirner.

Mamma Andersson’s new paintings at David Zwirner allow you to really indulge in your loneliness. Right now, we are all the small, solitary, socially distanced horse in the top corner of her 2019 canvas Solo. The animal peers over a vast desert, pockmarked with umber patches of grass and deep green shrubs. Working with oil bars and acrylics on canvas is relatively new for the artist, whose earlier works comprised oil on board. The swap allows her to privilege feelings over specific events.

Mamma Andersson

View Slideshow

6 Images

The Swedish artist is renowned for moody scenes and subdued palettes. Her imagined landscapes and interiors evoke nostalgia untethered from a particular time or place. Last Waltz (2020), for example, features a table laden with dark bottles. Behind it, a green rectangle with a pink-and-blue pattern gradually reveals itself to be a window, facing out onto a fantastical, fauvist approximation of weather. The walls blur into fuzzy green and blue swirls, as though the room itself is drifting into memory.

Though the show’s title, “The Lost Paradise,” refers to a trio of paintings that detail female equestrians seen from behind, a sense of absence, or of tales half-finished, pervades all of Andersson’s frames.

—Alina Cohen

Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, Rome

Frida Orupabo, installation view of “12 self portraits” at Sant’Andrea de Scaphis, Rome, 2020. Photo by Roberto Apa. Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York/Rome.

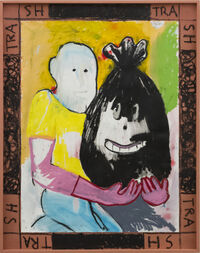

The title of Frida Orupabo’s show at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, “12 self portraits,” is an intentional misnomer—the sculptural collages that populate the Roman gallery space are not self-portraits, but sourced from an extensive archive of historical photographs. “I don’t use images of me in my collages,” the artist explained in a video on the gallery’s site. “I use other people, but I break it up.”

That “breaking up” adds another wrinkle to the show’s title. The works here are intentionally fractured, featuring relocated and recombined aspects of the body; there is hardly a concrete “self” in sight. While almost all of the works feature the faces of black women, the bodies those faces are attached to range from childish or cherubic figures to pure sculptural forms, obelisks, barbells, or ominous crossbones.

Frida Orupabo

View Slideshow

6 Images

The sense of decapitation permeates and becomes something deeper, a sort of truncated and repossessed history felt in both the form of the sculptures as well as their placement, from the fresco-like wall hangings to the totemic floor pieces, scattered like the pilfered treasures of a tomb. Questions of racial and colonial violence intermingle with questions of a more metaphysical bent. Is the self one thing, or is it recombinant? Is it free-floating or rooted in place? More pointedly—how is selfhood granted to the original subjects of these sculptures, separated as they are from their bodies and their past? Are the works portraits, or are they possessions?

—Justin Kamp

Galería OMR, Mexico City

Pia Camil, installation view of “Ríe ahora, llora después” at Galería OMR, Mexico City, 2020. © 2020. Photo by David Díaz Medina. Courtesy of the artist and OMR, Mexico City.

Pia Camil’s drawings are bursting with frenetic energy and yet feel very enclosed—a familiar sensation in the time of social distancing. Aptly titled “Ríe ahora, llora después” (“Laugh now, cry later”), Camil’s current show at Mexico City’s Galería OMR perfectly encapsulates what it means to contain yourself. Author Gabriela Jauregui described these works as “boxes of pleasure. And pain.”

Pia Camil

View Slideshow

6 Images

These diaristic works are impulsive—and represent a surprising break from the Mexican artist’s typically cerebral practice. Explosive gestures struggle to be confined within their borders as stream-of-consciousness captions attempt to name these erratic states. A yellow snake and blue fish take residence in the belly of a pregnant woman’s torso, feverishly colored in crimson. The image is framed with the tongue-in-cheek caption “Hormonal Abun(dance).”

While, in the past, Camil has explored the aesthetics and politics of consumerism and urban ruin in her work, this show is a remarkable opportunity to see works that cull from her personal experiences and emotions.

—Shannon Lee

Perrotin, New York

Bharti Kher, installation view of “The Unexpected Freedom of Chaos” at Perrotin, New York, 2020. Photo by Guillaume Ziccarelli. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

A white spiral of 10,000 meticulously placed bindis opens “The Unexpected Freedom of Chaos,” Bharti Kher’s first solo exhibition in New York in eight years. Titled Virus I (2010), the wall installation is part of an ongoing series, running from 2010 to 2039, where Kher pairs the Hindu symbol for the third eye with a list of yearly predictions and summaries. For 2020, the New Delhi–based artist writes, “Right wing ideologies find voice in leaderships across the world. Climate crisis caused by changes in the weather, becomes a major threat to the earth and its ecosystems.” Kher tackles the dire circumstances of our current reality with humor and an emphasis on repair and regeneration.

Bharti Kher

View Slideshow

6 Images

In Gentle Bitch and Cry me a River (both 2019), Kher adheres bindis in varying shades of blue and black onto shattered mirrors, accentuating the cracks rather than covering them up. While these mirrors line the walls of the gallery, Kher’s “Intermediaries” series of clay statue assemblages are scattered throughout the exhibition space. For these works, she breaks found objects, then combines mismatched fragments, creating new configurations that fuse the divine with the kitsch and mundane. In Self-portrait (2019), Kher presents herself as a vertically sliced statue of Saraswati—goddess of knowledge, music, and art—but half of the deity is replaced by a curving abstract sculpture.

Kher’s borderline iconoclastic process continues in Mr and Mrs from Model Town (2019). In the piece, a smiling pomegranate replaces the head of Parvati and a beheaded Shiva is joined with the body of Ganesha, resulting in a new family unit. Altogether, Kher imagines a multitude of possibilities from the chaos that she creates.

—Harley Wong

König Galerie, Berlin

Jorinde Voigt, installation view of “The Real Extent” at König Galerie, Berlin, 2020. Photo by Roman März. Courtesy of the artist and KÖNIG GALERIE, Berlin/London/Tokyo.

In her latest work, Berlin-based artist Jorinde Voigt offers a welcome moment for reflection in a time of such uncertainty. Her show “The Real Extent” at König Galerie in Berlin (and a concurrent show, “The State of Play,” at David Nolan Gallery in New York) continues her exploration of how our personal experiences and identities relate to the outside world and external conditions. As we navigate the impact of a global pandemic, Voigt addresses themes that remind us to examine our relation to our surroundings. “The Real Extent,” like much of Voigt’s work, aims to make objective sense of those things about our world that often feel unexplainable.

Jorinde Voigt

View Slideshow

6 Images

Voigt’s mesmerizing works on paper show layers of gentle curves and spiral etchings that mimic the cosmos. The exhibition’s title work, Immersive Integral / The real extent IV (2019), is a billowy blue scene marked with a dark splatter of ink and bold strokes of gold leaf. The exhibition also presents a wispy brass mobile sculpture, Betrachtung / Contemplation 6 (2019), which hangs delicately in the massive gallery space. Several faceted sculptures, titled Integral / Polyeder, 4-eckige Doppelpyramide (2018), lay across the floor; their sharp forms are brilliantly reflective. Though contrasting with the softness of the blue and yellow hues seen throughout the show, the structures subtly compliment the flecks of gold in Voigt’s large-scale drawings.

—Daria Harper

See more highlights from blue-chip galleries and explore Art Keeps Going.