Art

How Conservators Keep Masterworks of Outdoor Sculpture Safe

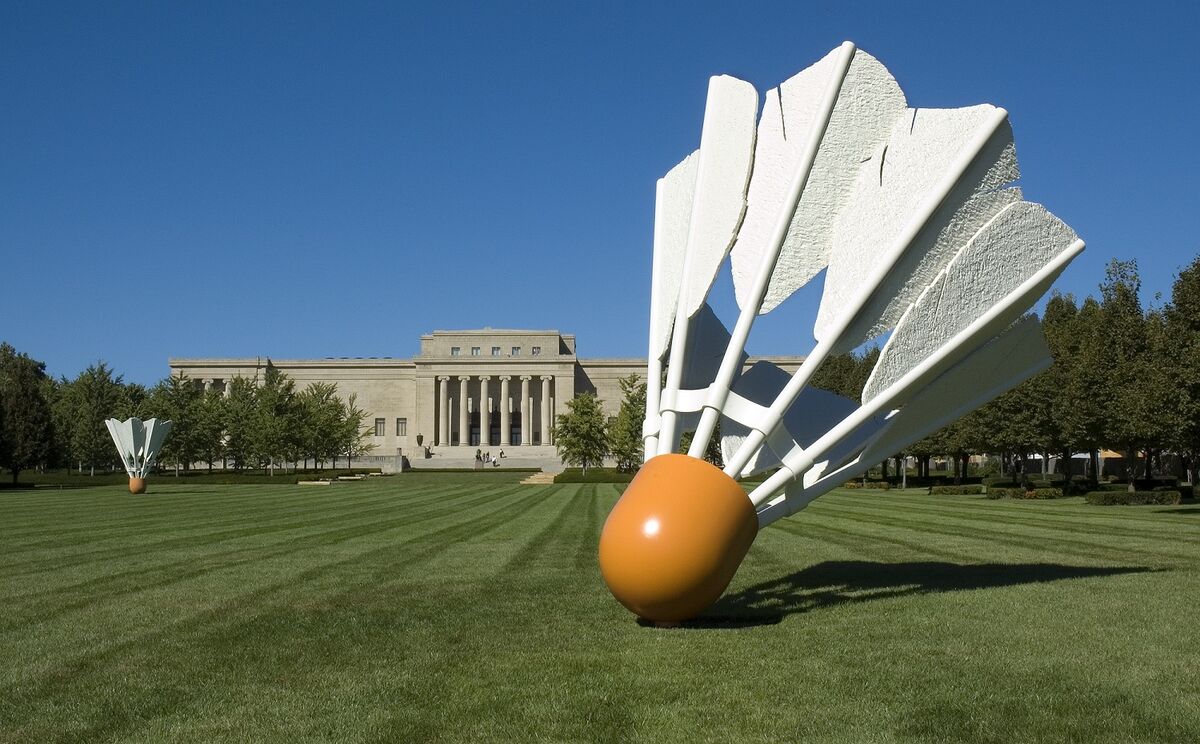

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Shuttlecocks, 1994. © Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. Courtesy of Nelson-Atkins Media Services / Louis Meluso and the Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City.

A

sculpture at New York’s Storm King Art Center just got a military-grade update. After years of exposure to the elements, the 23-foot-tall, matte-black, painted-steel City on the High Mountain (1983) needed a restoration. Storm King conservator Mike Seaman, working with the Getty Conservation Institute, decided on a durable solution: a special paint that the U.S. Army Research Laboratory has formulated for helicopters. At the end of the August, City on the High Mountain will return to the outdoor sculpture park after more than seven months, battle-ready.

Though the Department of Defense rarely gets involved with art institutions, the case study dramatizes a longstanding challenge that’s often invisible to the average sculpture garden visitor. How exactly does one go about protecting outdoor artwork?

Louise Nevelson, City on the High Mountain, 1983. © 2018 Estate of Louise Nevelson/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Jerry L. Thompson. © Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York.

According to Getty Conservation Institute associate scientist Rachel Rivenc (who worked on the Nevelson restoration with Seaman), “the sheer fact of being outdoors, exposed to the environment, rain, snow, or huge amounts of sunshine” makes for unpredictable decay. Additionally, the public is often free to engage with sculpture away from the watchful eye of guards—sometimes, artists even welcome these kinds of interactions (climbing, touching, walking atop). Yet, said Rivenc, “too much love is not always a good thing. The interaction can be detrimental for the preservation.”

Beyond the vicissitudes of the weather, external sources of deterioration come from materials both synthetic and natural. Rubbed-off sunscreen from a visitor’s curious hand is a nightmare for conservators; it’s especially difficult to remove. Dana Turkovic, curator at Laumeier Sculpture Park in St. Louis, Missouri, mentioned that bird poop requires a nonionic cleanser (gentler than everyday soaps).

Matte coatings on painted outdoor sculptures offer another struggle. Artists from Nevelson and

to

and

have all finished their work with low-gloss paints. These require “fillers”—various materials (like clay, lime, or earth) that decrease the amount of resin on the surface, and ultimately reduce the hue’s shine. When there’s less resin protecting pigments, said Rivenc, they’re prone to chalking, flaking, and fading.

Before cleaning: Tony Smith, Lipizzaner, 1976. Courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

After cleaning: Tony Smith, Lipizzaner, 1976. Courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Repainting a work, said Seaman, can be an arduous process. Enormous outdoor sculptures, some weighing in at multiple tons, would need to be removed from the lawn, trucked to a facility, stripped, and painted—with each step of the process being documented along the way. His team has to determine whether to clean off or remove the paint on the surface, whether it should be abrasively blasted off, and how the surface of the underlying material (pre-paint) should feel. Some areas may need chemical stripping.“We’re not just applying paint,” said Seaman. “We’re applying different coats of different types of primers to protect the substrate, and then to allow for a proper adhesion for a top coat.”

Sometimes, however, a certain amount of material corruption is actually integral to a sculpture. At Laumeier,

incorporated an abandoned 1929 swimming pool into a larger wood, stone, steel, and concrete structure that functions as a meeting place comprised of stairs, a raised platform, and a shaded pavilion.

The functional sculpture, Pool Complex: Orchard Valley (1983–85), hosts poetry readings, cocktails, and special events. Such use has weakened the architecture over the decades, and the park must be cognizant of safety hazards. Miss has visited Laumeier to consult on strategies for upkeep, and the discussion is ongoing. “She really feels strongly about it maintaining its natural life,” said Turkovic. The park may yet have to compromise on aesthetics to ensure visitor safety.

Mary Miss, Pool Complex: Orchard Valley, 1983-85. Courtesy of Laumeier Sculpture Park.

Many conservators noted that ongoing conversations with artists are crucial to ethical practices. Susie Seborg Anders, of Southern Art Conservation, LLC, once worked with

to discuss the pros and cons of different conservation approaches for one of his large-scale sculptures. “It was amazing to have his input and explain to him why we would make certain decisions from a conservation perspective,” she said. Ultimately, they were able to align their ideas about how to alter the work.

Seborg Anders recorded her discussions with Oldenburg, uploading them to a database created by the International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art. The organization maintains the archive (available only to members) to ensure that conservators have access to artists’ wishes, even after they’re deceased.

Joe Rogers, an object conservator for Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum and its Donald J. Hall Sculpture Park, has also worked with Oldenburg. The park owns four of his famed Shuttlecocks (1994), which do indeed resemble giant badminton accoutrements, scattered in varying positions across the lawn. “He wants them to look brand new,” said Rogers, “which is hard to do when people are climbing on them.” Accordingly, he must arrange consistent upkeep, using scaffolding and a hydraulic lift to reach the top of the nearly 18-foot-tall works. It takes at least four people to clean it at a time using mild detergent.

, in contrast, told the garden while he was still alive that he wanted his contribution, Rush Hour (1983/1995), to look—according to Rogers—as though it had been “in the ocean for a thousand years.”

Susie Seborg Anders with Claes Oldenburg looking at Giant Soft Fan, 1966-67, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Courtesy of Susie Seborg Anders.

’s Three Bowls (1990) is another particularly tricky work for Rogers and his crew. A blackening layer of graphite covers the exterior of the massive cedar sculpture, which comprises three 15-foot-tall conic forms. Every year, the work requires waterproofing. Additionally, to meet von Rydingsvard’s aesthetic requirements, the team must reapply the graphite with a brush every three years. For years, the artist used to visit the park to conduct the upkeep herself. Now, it’s the park’s responsibility. “It goes everywhere,” said Rogers. “It’s really kind of a mess.”

According to Cindy Burlingham, deputy director of curatorial affairs at the Hammer Museum, the biggest challenge for the museum’s Franklin D. Murphy Garden is “to make sure that the blades on the kinetic sculpture by

stay appropriately balanced so that they move freely with the breezes in the way the artist intended.” The sculpture, Two Lines Oblique Down, Variation III (1970–74), comprises a stainless steel Y-formation with arms that gracefully rise and fall as the wind passes. Rickey died in 2002, and the Garden honors his original vision.

When an artwork’s creator is deceased, conservators rely on their estates for guidance. To maintain outdoor sculptures by

and Alexander Calder, the Hammer Museum consults with the artists’ archives, which specify the correct type of paint for each work.

Flaking paint in a detail of Robert Indiana, LOVE (red outside violet inside), 1966-97. Courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Robert Indiana, LOVE (red outside violet inside), 1966-97. Courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Sometimes, an artist’s estate has more pressing business than consulting with conservators. Seborg Anders noted that one of her most demanding tasks at the New Orleans Museum of Art’s Besthoff Sculpture Garden is conserving Love, Red Blue (1966–97) by

. “The colors are faded significantly,” she said. As the estate has been “dealing with other things” (a raging legal fight over Indiana’s $28 million legacy, perhaps), Seborg Anders has developed a short-term plan to address issues of paint flaking and a long-term plan for repainting. She’s hesitant about taking more aggressive steps. “What level of damage [means it’s] too much to fix locally, and do we have to resurface?” she said. “Those are irreversible decisions that will also establish the protocol for the future preservation of the works.”

Sometimes, outdoor sculpture upkeep more closely resembles gardening. In 2013, Laumeier commissioned

to erect Topiary, which is comprised of three intricately shorn hetz juniper trees. “That’s a good metaphor for conservation,” said Turkovic. “It requires pruning, real care, maintenance, and someone who is very in tune with those materials. That’s a perfect example of what it takes to maintain all of the pieces here.”

Alina Cohen is a Staff Writer at Artsy.

Correction: A previous version of this article contained an error, which incorrectly stated that Rachel Rivenc was a scientist with the J. Paul Getty Trust. She is a scientist with the Getty Conservation Institute.