Family Function: Harm van den Dorpel’s Algorithmic Art

Perhaps some aspects of the creative mind can be stored in

code, but all of it? While the analytical capabilities of artificial

intelligence are recognized as “real,” many refuse to acknowledge that

simulations of taste can be equally authentic. The common-sense

consensus seems to be that aesthetic feeling is too complex to ever

quantify, as it is generated by dozens of factors, from class upbringing

and education, to social influences and pressures, to remembered and

learned preferences.

In Death Imitates Language, Harm van den Dorpel attempts to formalize artistic agency through an automated fitness function. Over the course of three months, the Berlin-based artist has developed an algorithm that learns his aesthetic choices as he expresses them over thousands of iterations and accretive steps. As the algorithm is perfected, the images it produces should suggest something like his taste and, eventually, come close to replicating it, possibly through a neural network that he will design. The system will not only measure van den Dorpel’s aesthetic choices, but also regenerate and simulate them in order to run without his input.

Death Imitates Language takes the form of a website populated by hundreds of stunning, strange, and difficult digital paintings. Six pieces have been pulled from the site and executed as UV prints on CNC-cut, laser-polished Plexiglas, and are featured in “wer nicht denken will fliegt raus,” a group exhibition organized by Heinrich Dietz at the Museum Kurhaus Kleve in Germany. (A seventh software piece shows an animation of all the paintings in the series.) The show—which includes eight other artists, including Hito Steyerl and Alice Channer—takes its title from a provocative saying by Joseph Beuys, which can be translated, “He who does not think will be thrown out.” In an interview, Dietz said he wanted to further explore Beuys’s suggestion that the engagement and interpretation of art is entirely contingent on the ability to think. The works by van den Dorpel challenge the notion that thinking and the capacity for making and appreciating art are exclusive to human beings.

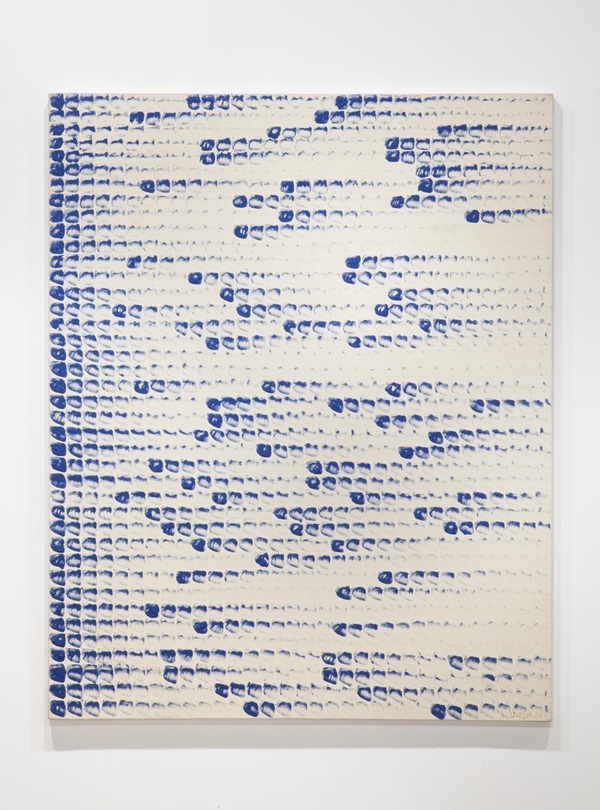

Each work in Death Imitates Language is the child of two parents, which themselves are the children of their own parents, all the way back down the page to Painting 0 and Painting 1, which van den Dorpel titled Adam and Eve. Eve is a blank white square; Adam is a white, crumpled sheet, with a spiral of tiny circle outlines blossoming in the upper central field. At genesis, Adam and Eve passed down information sequences in phrases of code that determined the visual characteristics for each of their descendants by generating constellations of colors and forms, their repetition, scale, degree of transparency, and arrangement within the frame. The qualities are encoded as chromosomal sequences of 0s and 1s: Adam is set to all 0s, and Eve is all 1s.

Van den Dorpel based his algorithm on one widely used in the technical sciences—to refine radio antennae, for instance. The program chooses whether a “gene” will be taken from parent or both parents. Variation emerges over time as van den Dorpel steps in to select which children will live, which will breed, and which will get killed off. The ones that live fade through a simulated aging process.

As you scroll through the site, aspects repeat, shift, and evolve from one family to the next. Blurry spots, reminiscent of viral forms in a petri dish, multiply. Abstractions of diseased eyes on an ophthalmologist poster contract and expand. Heavy black L-shapes cut into outlines fine as needlepoint. Galactic spirals like the one in Adam move across the field and vanish, only to emerge a generation later, double the size or mirrored or with dozens more arms.

Eventually, the thousands of micro-feedbacks fed into this algorithm should constitute what van den Dorpel calls “a Harm-like taste.” Death Imitates Language suggests that the positive decisions that users offer to a network say more than they realize about what they really enjoy. “The algorithm itself is the aesthetic process,” van den Dorpel wrote in an email. “The ideology is in there, in the code.”

Van den Dorpel further pointed out how sudden shifts in art appreciation can result from social and political movements or the influence of institutions, art historians, and other hierarchical figures. “The outcome of such a process can be aggregated, analyzed, and reproduced by algorithms,” he said. But he added that algorithms couldn’t cause them. No current computational system could innovate or redefine taste. Human aesthetic feeling requires context. It occurs in a body that has grown up over time in a social matrix, with memories and experiences shaped by interpersonal relationships.

This past February, the Musée du quai Branly in Paris let a robot art critic named Berenson loose in its halls. The unsettling apparatus wore a white scarf and a bowler hat, tottered about the galleries, sharing its negative and positive opinions about pieces after analyzing museumgoers’ facial expressions. The project was most successful as a formal reflection of one crucial aspect of how we cultivate our own taste: by mimicking or rejecting the cues of our peers.

Death Imitates Language can replicate van den Dorpel’s aesthetic decisions. But it won’t object to his taste, or develop its own. “It might sound funny and unreasonable to expect this from an algorithm,” van den Dorpel said, “but for me, such traits would be prerequisites of intelligence.” He added that he admires the work of philosopher Hubert Dreyfus, whose research is based on what computers cannot yet do.

Anxiety over whether the creative mind could be stored in code often raises another considerable specter of fear, namely, of obsolescence. However, van den Dorpel’s work does not suggest that an aesthetic sensibility can make artificial intelligence fully human. Automata that can make and differentiate art are not a threat to personhood.

Some taste is simulated, and some taste is human, and they could exist in a hybrid system or a feedback loop. Van den Dorpel noted that his work of training the algorithm has influenced his own sensitivity for shapes and colors. As artificial intelligences approximate human attitudes and inclinations, they can be considered companions, not competitors. A future robot art critic running on the neural network that van den Dorpel may someday build could only enhance art criticism, challenging human and humanoid aesthetes to refine their own language for discussing taste.

In Death Imitates Language, Harm van den Dorpel attempts to formalize artistic agency through an automated fitness function. Over the course of three months, the Berlin-based artist has developed an algorithm that learns his aesthetic choices as he expresses them over thousands of iterations and accretive steps. As the algorithm is perfected, the images it produces should suggest something like his taste and, eventually, come close to replicating it, possibly through a neural network that he will design. The system will not only measure van den Dorpel’s aesthetic choices, but also regenerate and simulate them in order to run without his input.

Death Imitates Language takes the form of a website populated by hundreds of stunning, strange, and difficult digital paintings. Six pieces have been pulled from the site and executed as UV prints on CNC-cut, laser-polished Plexiglas, and are featured in “wer nicht denken will fliegt raus,” a group exhibition organized by Heinrich Dietz at the Museum Kurhaus Kleve in Germany. (A seventh software piece shows an animation of all the paintings in the series.) The show—which includes eight other artists, including Hito Steyerl and Alice Channer—takes its title from a provocative saying by Joseph Beuys, which can be translated, “He who does not think will be thrown out.” In an interview, Dietz said he wanted to further explore Beuys’s suggestion that the engagement and interpretation of art is entirely contingent on the ability to think. The works by van den Dorpel challenge the notion that thinking and the capacity for making and appreciating art are exclusive to human beings.

Each work in Death Imitates Language is the child of two parents, which themselves are the children of their own parents, all the way back down the page to Painting 0 and Painting 1, which van den Dorpel titled Adam and Eve. Eve is a blank white square; Adam is a white, crumpled sheet, with a spiral of tiny circle outlines blossoming in the upper central field. At genesis, Adam and Eve passed down information sequences in phrases of code that determined the visual characteristics for each of their descendants by generating constellations of colors and forms, their repetition, scale, degree of transparency, and arrangement within the frame. The qualities are encoded as chromosomal sequences of 0s and 1s: Adam is set to all 0s, and Eve is all 1s.

Van den Dorpel based his algorithm on one widely used in the technical sciences—to refine radio antennae, for instance. The program chooses whether a “gene” will be taken from parent or both parents. Variation emerges over time as van den Dorpel steps in to select which children will live, which will breed, and which will get killed off. The ones that live fade through a simulated aging process.

As you scroll through the site, aspects repeat, shift, and evolve from one family to the next. Blurry spots, reminiscent of viral forms in a petri dish, multiply. Abstractions of diseased eyes on an ophthalmologist poster contract and expand. Heavy black L-shapes cut into outlines fine as needlepoint. Galactic spirals like the one in Adam move across the field and vanish, only to emerge a generation later, double the size or mirrored or with dozens more arms.

Eventually, the thousands of micro-feedbacks fed into this algorithm should constitute what van den Dorpel calls “a Harm-like taste.” Death Imitates Language suggests that the positive decisions that users offer to a network say more than they realize about what they really enjoy. “The algorithm itself is the aesthetic process,” van den Dorpel wrote in an email. “The ideology is in there, in the code.”

Van den Dorpel further pointed out how sudden shifts in art appreciation can result from social and political movements or the influence of institutions, art historians, and other hierarchical figures. “The outcome of such a process can be aggregated, analyzed, and reproduced by algorithms,” he said. But he added that algorithms couldn’t cause them. No current computational system could innovate or redefine taste. Human aesthetic feeling requires context. It occurs in a body that has grown up over time in a social matrix, with memories and experiences shaped by interpersonal relationships.

This past February, the Musée du quai Branly in Paris let a robot art critic named Berenson loose in its halls. The unsettling apparatus wore a white scarf and a bowler hat, tottered about the galleries, sharing its negative and positive opinions about pieces after analyzing museumgoers’ facial expressions. The project was most successful as a formal reflection of one crucial aspect of how we cultivate our own taste: by mimicking or rejecting the cues of our peers.

Death Imitates Language can replicate van den Dorpel’s aesthetic decisions. But it won’t object to his taste, or develop its own. “It might sound funny and unreasonable to expect this from an algorithm,” van den Dorpel said, “but for me, such traits would be prerequisites of intelligence.” He added that he admires the work of philosopher Hubert Dreyfus, whose research is based on what computers cannot yet do.

Anxiety over whether the creative mind could be stored in code often raises another considerable specter of fear, namely, of obsolescence. However, van den Dorpel’s work does not suggest that an aesthetic sensibility can make artificial intelligence fully human. Automata that can make and differentiate art are not a threat to personhood.

Some taste is simulated, and some taste is human, and they could exist in a hybrid system or a feedback loop. Van den Dorpel noted that his work of training the algorithm has influenced his own sensitivity for shapes and colors. As artificial intelligences approximate human attitudes and inclinations, they can be considered companions, not competitors. A future robot art critic running on the neural network that van den Dorpel may someday build could only enhance art criticism, challenging human and humanoid aesthetes to refine their own language for discussing taste.