|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

Friday, April 29, 2016

The Growing World of Degree-less Art School

The Growing World of Degree-less Art School

Studio art programs that don’t grant degrees are exploding in popularity

By Daniel Grant • 04/27/16 3:55pm

FacebookTwitterLinkedInGoogle+Email

. Illustration by Jon Krause

The Art Students League is one of a growing number of colleges, universities, nonprofit arts organizations and art schools around the country that have developed full-time programs for artists that do not confer any degree. For some of these budding artists, getting a college degree in art is less important than just learning how to make it.

“It wasn’t at all clear to me that going to college and getting a degree would help my career any more than getting a certificate,” said Jennifer Frudakis, a sculptor in New Jersey who enrolled in the four-year certificate program at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1980 directly out of high school and never earned a college diploma. “There’s no guarantee that a degree would make me a better artist or more likely to sell my work. At PAFA, I learned a trade, and I make a living as an artist.”

A growing number of the students in PAFA’s certificate program are in the 18 to 20 age range and “really want to focus on their studio practice, unencumbered by other coursework that are part of the traditional Bachelor of Fine Arts curriculum,” said Andre van de Putte, dean of enrollment at the art school. (In addition to its one- and four-year certificates, PAFA has a BFA program.) The degree program and four-year certificate have identical application requirements, and first-year students take the same foundation courses. It is in the second year that liberal arts classes are introduced into the curriculum of the BFA students, while those in the certificate program continue to just concentrate on studio. The students work in an “atelier-style” mentorship with professional artists and, in their third and fourth years, receive private studios in which to pursue their own work while continuing to receive guidance and feedback from faculty.

A sculpture class at PAFA. Photo: Courtesy of PAFA

She said that her mother, also a painter, supported her decision. She understood “how little value a BFA has when you start submitting work to galleries or entering into competitions,” Ms. Engberg said. “All they care about is the quality of the work. She understood that I was going to get the best quality of training from an atelier. My father, who is an airline pilot, was less supportive of the decision in the beginning. He felt that I should get a BFA first and then attend an atelier after.” But, eventually, he came around.

Those with only high school diplomas are by no means the only students in these programs. The age range and backgrounds are quite diverse; some are retirees, some are middle-aged and looking to learn new skills in order to change careers, some are parents returning to school after raising children, others already have degrees and want to improve their art skills before applying to an MFA program, like a post-bachelor’s for art. “A number of them have been in studio art programs in college, but they didn’t spend much time in the studio, and their portfolios are not strong,” said Mary Fisher, school administrative director at the National Academy Museum and School of Fine Arts in New York, whose Studio Art Intensive program takes two or three years to complete. After all, having a degree in art doesn’t mean someone knows how to make things.

Art school itself is not for every student, and those in the certificate program at PAFA may be even more tunnel-visioned than their BFA counterparts. Certificate students “can’t dabble here to see what they like,” Mr. van de Putte said. “It is for very unique students, who know this is going to be their career.”

It is a unique person, generally, who will spend years and thousands of dollars at a school with only a certificate of completion to receive at the end. “I originally started in the diploma program here, but in the end switched into the BFA program,” said Pawel Przewlocki, a sculptor and admissions counselor at the School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, who earned both a diploma—that school’s version of a certificate—and the degree in 2014. “Part of my thinking was, ‘What will people think of a diploma?’ I worried that the diploma program would be thought of as adult daycare, as just making stuff, not a rigorous program.”

Claudia Sohrens, a photographer who earned a certificate from the International Center for Photography in 2002 and currently teaches there, noted that she lists the certificate program on her resume when she is looking for a teaching job (she also teaches at Parsons), but not on the resume she uses as an artist, for instance, when presenting herself to a gallery owner. “It’s not relevant in that context,” she said.

A figure structure class at GCA. Photo: Courtesy of GCA

The costs of attending are roughly the same for degree and non-degree students. Annual tuition for BFA students is currently $39,928, compared to $35,400 for diploma students. At PAFA, both BFA and four-year certificate students pay annual tuition of $32,960.

Certificate programs at non-degree-granting art schools can be considerably less expensive. Tuition for the four-year certificate program at the Art Students League is $3,300 per year, while the National Academy charges $16,500 for full-time students. Tuition for the certificate program at the New York Studio School is $7,425 each semester, making the total cost of its three-year program $44,550. On the other hand, the one-year certificate program offered by New York’s International Center for Photography is a regular college-priced $32,817 for the 2016-2017 academic year, not including the $100 application fee and annual $1,500 lab fee. It is also important to remember that non-degree-granting schools do not qualify for federal financial aid, although individual institutions may have their own scholarship funds.

Just as with Mr. Przewlocki, it is possible that certificate students may move into degree programs at colleges that have both, although no one knows of instances of the opposite taking place. At art schools that do not offer degrees, students must take it on faith that their time and money will lead to something positive. Confidence cannot be in short supply. “It is a lot of time and money being spent not to get a degree,” said Parsons’ director of continuing education, Melinda Wax. Women appear to be more apt to take a flyer on a multi-year non-degree art program than men. A majority of students at the Art Students League, PAFA, Parsons, North Seattle Community College, the School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the International Center for Photography, the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, the New York Studio School, Lyme Academy College of Fine Arts and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago are women. Perhaps women are more confident than men that their skills are credential enough.

Collecting 101 | How to Really, Truly Appreciate a Work of Art

INSIDER ACCESS TO THE WORLD’S BEST ART

THREE DAYS ONLY! 10% OFF SITE-WIDE AND 20% OFF ARTSPACE EDITIONS.

Valid 04/28/16 through 04/30/16 at 11:59pm EST. Learn More |

Download the Artspace mobile app and view artwork in your own home! download now ▸

|

Collecting 101

How to Really, Truly Appreciate a Work of Art

By Artspace Editors

April 28, 2016

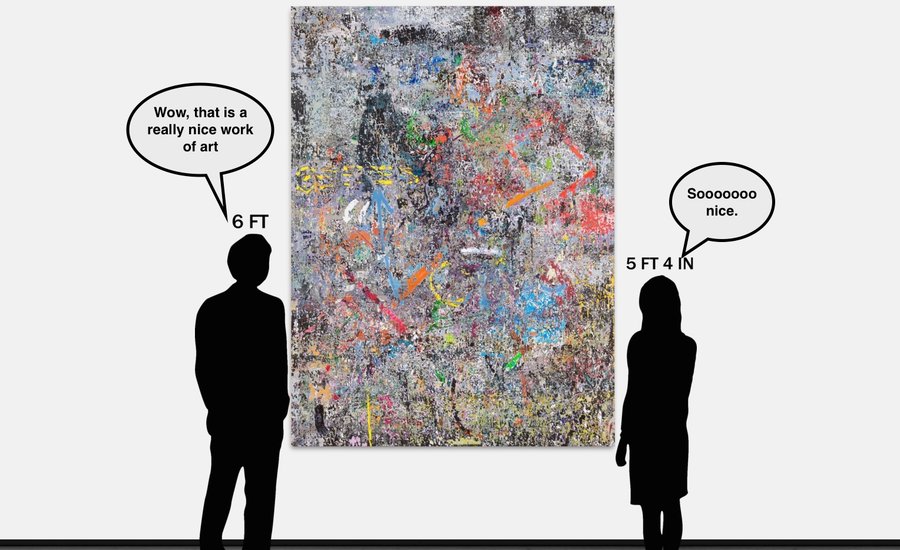

Connoisseurs admiring Andrew Jensdotter’s "Wired" – available on Artspace for $12,000

Some people might tell you that taking in a work of art is no different from gazing upon a beautiful flower, or a spectacular sunset. But ask yourself: do you really know how to look at a flower? Can you parse the various biological marvels on display? Are you perhaps missing something? Art is no different—there are places to inspect, aspects to weigh, artistic skills to suss out and savor. These, of course, will differ from person to person, but here are a few things to look for (other than the obvious beauty-related ones) that will help you really, truly appreciate a work of art.

1. HOW WAS IT MADE?

When you look at it, most art just sits there, static, a picture or object on display. But the sensitive eye can rewind the video tape, so to speak, and read the way the artwork was constructed. Were the brushes laid down fast or sedulously? Where was the camera placed? Like a detective at a crime scene, take the time to unravel the way the artwork in front of you as a record of a performance—one that expressed the artist’s virtuosity.

2. WHAT'S IT MADE OUT OF? (BE CAREFUL)

Artists, modern-day alchemists, love to transmute. A nail poking out from a stick of wood, in the hands of Susan Collis, can be pure platinum; a church by Al Farrow may be made from bullets; Amber Cobb’s cloth dangling from the wall might be silicone. As for paintings, marvel in the fact that each stroke of paint consists of pigment—essentially, colored dirt—suspended in viscous matter, which the artist conjures to do their bidding.

3. DOES IT SET YOU FREE?

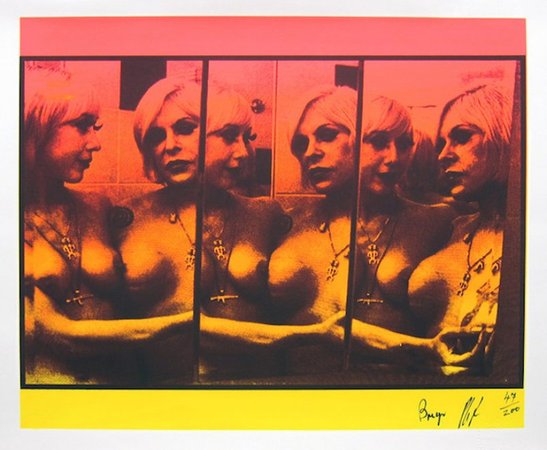

Artists often operate from a step off the mainstream, using an outsider’s vantage to offer new perspectives on things we often take for granted and suggest possible alternatives. These can relate to anything from the way Picasso saw a bull’s head in a bicycle seat to Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographic revelation that male sexuality has a wide ranges of orders that aren’t listed on the normative menu. Allow these works to untether your imagination.

4. HOW DOES IT CONNECT TO OLDER ART?

Harold Bloom wrote of the “anxiety of influence,” and artists are acutely aware of their places within the traditions of their mediums. Sometimes, as in the case of Jose Dàvila, they try to harmonize with their artistic forebears, making work with reverent reference to what came before; others, like Alan Magee, strive to exorcise their influences. As with a note on a musical score, the artwork you’re looking at may depend on one that came before for its meaning. Try to determine if that’s the case.

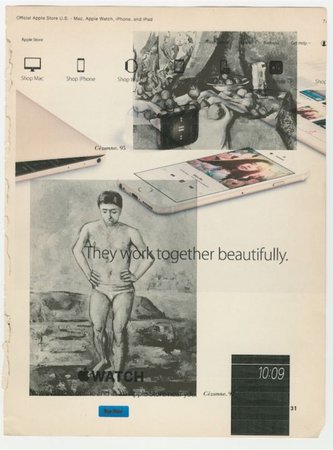

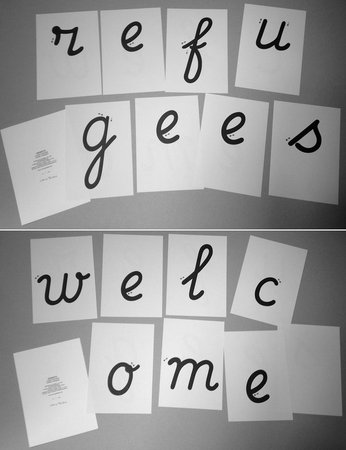

5. HOW DOES IT CONNECT TO SOCIETY?

Art doesn’t have to be “about” anything, really, but sometimes it’s about you. Or your friends. Or your political order. Or the fate of people half a world away. Artists frequently use their position to put their own particular lens on society, illuminating ills, underscoring hypocrisies, offering potential futures, or delving into resonant traumas of the past. If that’s the case, take the time to decode and absorb the artist’s message.

6. IS IT AVANT-GARDE?

Think of artists as the scouts of their tribe, slipping out in the early half-light to explore the uncertain terrain ahead. What they bring back might not look like art—it might be confusing, unrecognizable, irritating. When you see a work that you just can’t place—as in, it’s not a painting or anything else you’ve seen before—and its disagreeability makes you uneasy, pay close attention. It may be the next breakthrough in art.

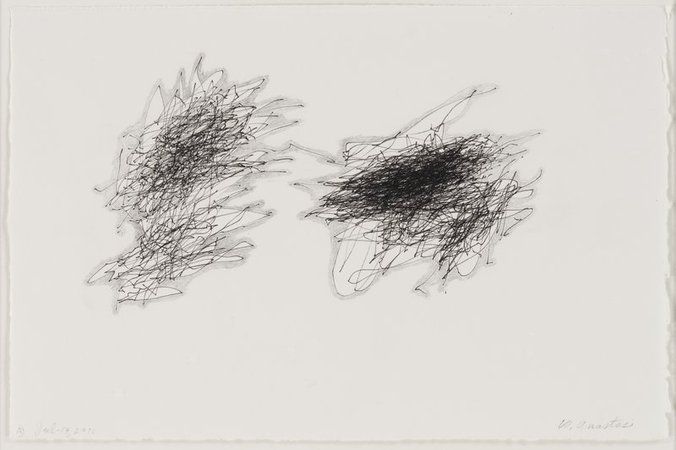

collect process-oriented art

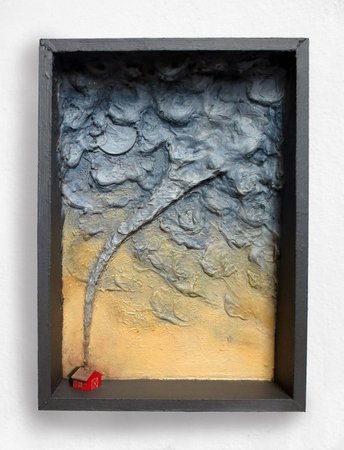

collect art with piquant materiality

collect art that sidesteps convention

collect art that connects to older art

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)