Artiquette is a series that explores etiquette in the art world.

How do you make it in the art world? It’s a magical formula

that involves, talent, drive, grit, and yes, the ability to promote

oneself. Unfortunately, talking up your own artwork, projects, and ideas

can be a delicate balancing act.

To help you walk that line, artnet News has rounded up a

list of mistakes to avoid in self-promotion. This advice applies not

only to artists looking to make a name for themselves but also to

everyone navigating the thorny issues involving self-promotion:

Galleries, museums, and publicists, take heed.

Related: Your Ultimate Guide to Becoming a Successful Artist

Actor

John O’Hurley emerges from a prop can of Spam during a launch event to

introduce “Monty Python’s Spamalot” at the Wynn Las Vegas in 2007.

Courtesy of Ethan Miller/Getty Images.

1. Don’t spam your audience.

No one likes to feel bombarded. As Hyatt Mannix, the communications manager at

High Line Art,

told artnet News in an email: “You are likely to lose interest from

your followers if you post more than twice in the span of 30 minutes.”

This applies to emailing art writers as well. On Monday,

July 4, while many in the US were out grilling hamburgers, a man who

goes by the moniker “Moltenglue Drywallmud” for email purposes chose

instead to send me no less than nine emails between 2:30 p.m. and 2:44

p.m. Unsurprisingly, those were the only messages I received at that

time. (Despite having different subject titles, each included

the same painting in the attachment.)

Related: Artiquette: How to Take a Winning Selfie With an Art Star

2. Don’t put out an underwhelming press release.

It doesn’t matter how great the work is: If you aren’t able to

communicate your message clearly, it’s highly unlikely anyone will pick

it up.

One of my favorite stories that I wrote last year, about how a curator identified

a long-lost Fabergé egg surprise in

the British royal family’s art collection, almost didn’t get written

because of the hard-to-parse email announcing the discovery.

You might think your work speaks for itself, but that’s not always the case.

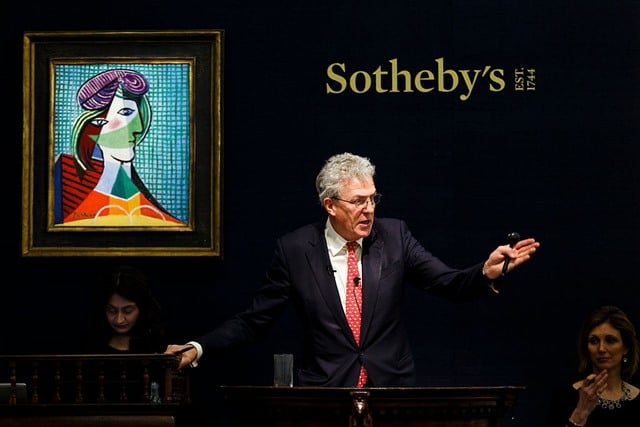

Gagosian Gallery. Courtesy of the gallery.

3. Don’t send galleries unsolicited artwork.

A few months ago, in a Facebook post that has since been since been

removed, a Brooklyn gallery owner complained about being inundated with

emails full of artwork from artists she had never met who were seeking

representation:

Dear portfolio-link sending artists,” she wrote. “It doesn’t

work like that with galleries. This is like walking up to a girl and

asking if you can fuck her. You need to meet the gallerists in person,

get to know their taste and interests and find where your work fits,

thoughtfully.”

Avoid this aggressive approach by identifying a gallery you

think might be a good fit, working your connections, and seeking a

personal introduction, rather than cold emailing.

Related: Artiquette: 10 Tips for Dressing the Part of the Art Connoisseur

4. Don’t just email anyone.

Whatever it is you’re pushing, it isn’t going to appeal to everyone. Do

your research, and figure out who, be it a journalist, a gallery, or a

collector, has expressed interest in similar projects in the past. This

is who you want to target.

As arts publicist Molly Krause, founder of

Molly Krause Communications,

put it in an email to artnet News: “Just because someone writes about

art doesn’t mean that he or she necessarily covers upcoming gallery

exhibitions, and just because someone covers upcoming gallery

exhibitions doesn’t mean that he or she necessarily writes about

anything other than, say, photography. Be respectful.”

5. Don’t overwhelm your audience.

How many photos should you share of the work? Mannix warned against both

using too many images and having too many: “Don’t underwhelm or

overwhelm,” she wrote.

Be considerate of download times and choose low resolution

images. Remember, as Mannix points out, “you don’t want to clog up

anyone’s inbox.”

Related: Artiquette: 10 Tips for Pricing an Artwork

A Christie’s staffer with Henry Moore’s sculpture Reclining Figure No. 2 (conceived in 1952) at Christie’s King Street, London, in 2015. Photo by Rob Stothard/Getty Images.

6. Don’t forget the 5 Ws.

When approaching someone with a pitch, lay out what you’re promoting,

and be as clear as possible. “Don’t forget to tell us what exactly your

work is. Is it a painting? Is it a sculpture?” Mannix wrote. “It’s

helpful to ask yourself if you’re explaining who, what, where, and (a

very brief) why.”

Related: The Ego-Centric Art World is Killing Art

7. Don’t make your audience angry.

If you’re consistently getting radio silence in response to your efforts

at self-promotion, leave well enough alone. Trim your mailing list in

an effort to reach out only to those you really think are interested.

And definitely let people opt out.

Danielle Wu, a gallery associate at Galerie Lelong, told me

in a Facebook post that her pet peeve is when people are “emailing

regularly and not including a way to unsubscribe.”

8. Don’t forget about links.

One big no-no is putting a link in your Instagram caption. “We can’t

click it!” Mannix explained. “Always put the link in your bio, where

visitors to your page can easily follow a link to visit your website.”

Greek

Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras and Russian President Vladimir Putin

visit the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens on May 27, 2016.

Courtesy of THANASSIS STAVRAKIS/AFP/Getty Images.

9. Don’t be cryptic.

Between mid-March and mid-May, I received eight bizarre emails from a

man I will call Bob. The emails had subject lines like “Question the

monopoly” and “Western decline,” and were addressed to me, first and

last name, and artnet.com, and were also sent to our editor-in-chief,

Rozalia Jovanovic.

Bob, who appears to have some sort of project about

non-Western art, always asked a vague question, such as “Do Western

governments discourage Western identity? Please consider.” He included a

link to his website in his email signature every time, but I never felt

compelled to visit it—nor, to be honest, to open his subsequent emails,

save for the purposes of this story. If Bob can’t take the time to

explain what the heck it is he’s doing, why should I bother to try and

find out on my own?

Related: Artiquette: 11 Tips to Surviving a Gallery Dinner

10. Don’t exaggerate.

Using Donald Trump-esque “truthful hyperboles” to enhance or lie about

your work or your resume might help in the short term, but it is a

faulty long-term strategy. The truth will eventually emerge, and you

don’t want to be caught in a compromising position.

Follow artnet News on Facebook.