THE PHAIDON FOLIO

"Art Is Not About Skill": Benjamin Buchloh Interviews Lawrence Weiner On His Sensual Approach to Conceptual Art

Lawrence Weiner began his career at the young age of 19 when he simultaneously detonated four explosives on the corners of a field in Marin County, California in an artwork he called Catering Piece. The heated gesture skyrocketed Weiner on a trajectory that landed him a key role in the conceptual art movement in the 1960s, when his work largely involved writing about hypothetical projects without actually making them, allowing his work to exist solely in the minds of his viewers. In 1968 (the year Sol LeWitt wrote Paragraphs on Conceptual Art), Weiner wrote Declaration of Intent:

1. The artist may construct the piece.

2. The piece may be fabricated.

3. The piece need not be built.

Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests within the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.

2. The piece may be fabricated.

3. The piece need not be built.

Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests within the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.

In the decades that followed, Weiner produced sculptures, films, artist books, and even CDs. Here, in an excerpt from Phaidon’s Lawrence Weiner monograph, Benjamin Buchloh speaks with the artist about design as a power system, sculpture as a gesture, and art as sensuality.

Benjamin Buchloh: I was always puzzled by your insistence that you executed Cratering Piece as early as 1960. Thinking in terms of historical context and frameworks, of models and paradigms, it seems almost impossible to imagine that anybody in 1960 could have gone out in the desert and would have set off a series of small TNT explosions declaring them to be a sculpture as you did in that work.

Lawrence Weiner: It was not in the desert; it was a national park. I wish I were as radical and revolutionary as historians would like to make out, but I was an eighteen year-old kid. I found myself in San Francisco around the City Lights bookshop and the Discovery bookshop and I was working around people like John Altoon, Bruce Connor, and others. Here I was, reasonably intelligent, with an enormous knowledge of what was going on, I must say. There were artists performing all over the place, doing happenings, performances, other things. My deciding to make sculpture by blowing holes in the ground, yes, in the light of my history, it is a big deal. In the light of what the hell was going on, it was just another artist out there, doing another sculpture park thing, using explosives, using performances, using tons of steel. This was all normal.

I had gotten to California by hitchhiking my way across the country, building structures, and constructing things everywhere I went, leaving them on the sides of the road. The Johnnie Appleseed idea of art was perfect for me: Johnnie Appleseed spread apple seeds across the United States by just going out on the road and spreading apple seeds. I do not know if this is true, but I would love it to be.

The next phase of your work was the early paintings, particularly the Series of Propeller Paintings (1960-65)?

I was making the strangest kind of paintings. I was in a very distressed state about the political relation of the artist to society and I knew that the artist’s lifestyle was something that I was determinedly going to hold on to because in fact it was a better lifestyle than that of the lower middle class from which I had come. It left me a little bit more freedom to function as I wanted to. I had gone to Europe in 1963, trying to collate where I was going to stand, whether I was going to do this or do that. A lot of things led up to these paintings. I began to understand things that were being discussed in the context of the painting of emblems. I had an old television set which only had one channel, with signals that I watched all night. That became my modus operandi. I began to make these paintings, all in different sizes and all in different shapes and all at the same price. As if that really mattered, but I thought it did at the time.

And you used commercial enamel paint for all of them, like Frank Stella did at the time?

Whatever. Silver paint, aluminum paint, sculpmetal, commercial enamels, crap I found out on the street, paint that I invented myself. Anything. Impasto. I was using all the things that people use to make paintings. You can spray it, stripe it. Name me all the painting conventions you can think of. All the things your parents ever taught you. These paintings then led to the cut-out sculptures from 1966 and they led to this other stuff, the notched paintings. They are paintings that can lie on the table. Some of them are made out of wood.

So these paintings were really reliefs and objects and that is where the traditional categories break down?

Those categories just completely collapsed on me. I wanted them to collapse but I was not going to hasten their collapse. I was going to follow it through and I followed it through to where it collapsed. The bridge no longer supported me. Great. Got me across the water to here. I am a happy immigrant.

Did you know Stella’s “black paintings” at that time?

I remember seeing them when Frank Stella had his first one-person show at the Museum of Modern Art. I thought they were absolutely fabulous. I remember a PBS broadcast of Henry Geldzahler interviewing Frank Stella in the early 1960s. Stella looked plaintively at the camera and said, “My god, if you think these are boring to look at, can you imagine how boring they are to paint?” I was very impressed. I mean it. Extremely impressed.

What about Robert Ryman; were you aware of him? He appears to have been such an isolated figure. People seem to dismiss Ryman as somebody who was inarticulate and not reading the same books as everybody else.

Bob Ryman had a studio on the Bowery. He was a great person for me to go to talk to. I dropped by every once in a while and he was a very friendly man.

But unlike Stella’s, his work was not well-received in New York throughout the early and mid 1960s. Did you not think of Ryman as somebody who was important in deconstructing the conventions of painting?

No. In adding to painting: making it a viable thing that had something to do with our own sense of ourselves. I thought Ryman’s work was really, I don’t know about important, but absolutely marvellous. But at that time he did not have that kind of success. It took me a long time to be able to make a living as well. Those things happen.

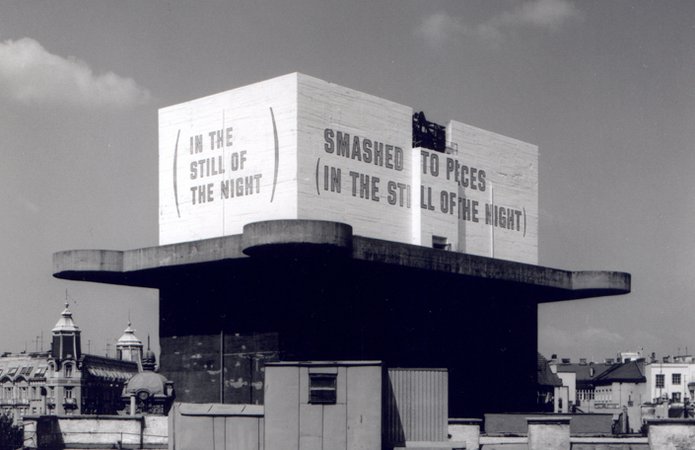

SMASHED TO PIECES (IN THE STILL OF THE NIGHT), 1991

SMASHED TO PIECES (IN THE STILL OF THE NIGHT), 1991

Obviously there are many trajectories in your work, but one of them is painting, and the dialogue with Jackson Pollock. But it is a dialogue mediated through looking at Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly and these two positions had already transformed painting when you started. I would like to talk about the relationship of language to painting. Language re-emerges in the painting of the 1950s in the work of two very different but closely related artists—Johns and Twombly—and I think they were both important in that sense for you. Their emphasis on language within the conception of painting itself seems to criticize Modernism’s foundational definition of an exclusive visuality. Formally organized visuality is of course still an element of your work but it is no longer the work’s primary foundation. This critique of modernist visuality and then simultaneous critique of representation and narrative become two central strategies of your work.

The Leo Steinberg article probably made me realize where Johns stood in my existence: this idea of how he placed the studio, not as a metaphor for the outside world but as an arena outside of the personal angst of other people whom I respected like Pollock or Kline or especially de Kooning. He was perhaps the coolest of all of them. He figured out that his life had more value than his place within society. Kline was not interested in that. Pollock—God knows what he was interested in.

I have always considered Twombly a beautiful painter. I thought that his work was absolutely exquisite: this was the life of a human being. This was class, without placing it within the context of modern art, without making it look important, but making it the way it was supposed to look. That is what made Ryman also such a fabulous painter for me: he was able to make it look the way it was supposed to look. Jasper Johns was doing that too. He did not ask me to be transcendental … he did not have to tell me that his found objects were a bridge.

I think that Rauschenberg in the end will turn out to be a far more important artist, because Rauschenberg did prat-falls, he took chances; Johns never took a risk in his life. What if we step aside for one second and then substitute one word “lifestyle,” public placement within our society, for “narrative.” You are talking about 1955 and narrative was not the problem, the problem was lifestyle.

I did not have that advantage of a middle-class perspective. Art was something else; art was the notations on the wall, or art was the messages left by other people. I grew up in a city where I had read the walls; I still read the walls. I love to put work of mine out on the walls and let people read it. Some will remember it and then somebody else comes along and puts something else over it. It becomes archaeology rather than history.

After you moved away from painting, you made work that looked as though it was closely related to minimalsculpture.

I worked damn hard on this too. I mean, we are of our times as we are trying to find out who we are.

So between 1966 and 1968 you redefine the painterly or sculptural object, its material structure, and its production process. You move on to a textual proposition that seems to be either the “mere” description or the theoretical definition of a material process, rather than its actual execution. From that moment onwards, you introduce a totally different set of terms for thinking about sculpture and I think its ramifications are hardly understood up to this very day. Rather than considering the conflicting genres of sculptural production (eg. artisanal or construction sculpture versus the ready-made object), you seem to address the process of sculptural conception and reception in contemporary audiences.

The audience is a hairy problem, but I must say I disagree. This has more to do with my politics than my aesthetics.

There seems to be a peculiar contradiction: on the one hand, you insist that sculpture is the primary field within which your work should be read, yet at the same time you have also substituted language as a model for sculpture. Thus you have dismantled the traditional preoccupation with sculpture as an artisanal practice and a material production, as a process of modeling, carving, cutting, and producing objects in the world.

If you can just walk away from Aristotelian thinking, my introduction of language as another sculptural material does not in fact require the negational displacement of other practices within the use of sculpture.

But why would it even have to be discussed in terms of sculpture, rather than in terms of a qualitatively different project altogether?

What would I call it? I call them “works,” I call them “pieces,” I called them whatever anybody else was coming up with that sounded like it was not sculpture. Then I realized that I was working with the materials that people called “sculptors” work with. I was working with mass, I was working with all of the processes of taking out and putting in. This is all a problem of designation. I also realized that I was dealing with very generalized structures in an extremely formalized one. These structures seemed to be of interest not only to me but to other artists at the time. I do not think that they were taken with the idea that it was language, but we were all talking about the ideas generated by placing a sculpture in the world. Therefore I did not think I was doing anything different from somebody putting fourteen tons of steel out. I said it was possible that I would build it if they wanted, I said it was possible to have somebody else build it, and then I finally realized that it was possible just to leave it in language. There was not a skill; art is not about skill.

In the post-war American context, the strategy of de-skilling responds first of all to the cult of gesture and of the artist’s hand in Abstract Expressionism. That is in fact one of the most crucial strategy changes within artistic practices re-emerging in the 1950s with Jasper Johns.

But I am questioning whether the skill of making the spoon is the point of being an artist, or whether the spoon that holds water is the point of being an artist. I am still vying for the fact that it is the thing itself that makes you an artist, not your acquired skills, not your special insights into the world or anything else.

So what defines the functional quality of the work if it is not its dimension to communicate most adequately with a certain type of audience?

For me, the making of sculpture, the placing of sculpture within cultural environments and in the public, is about allowing people to deal with the idea of mass, of other materials, the dignity of other materials, and to be able to figure out how to get around them if they are dangerous, get over them if they are easy, and lie on them if they are sensual. My use of language is not in any way designed and it has never been. I think that I am really just a materialist. In fact I am just one of those people who is building structures out in the world for other people to figure out how to get around. I am trying to revolutionize society, not building an new department in the same continuum of art history.

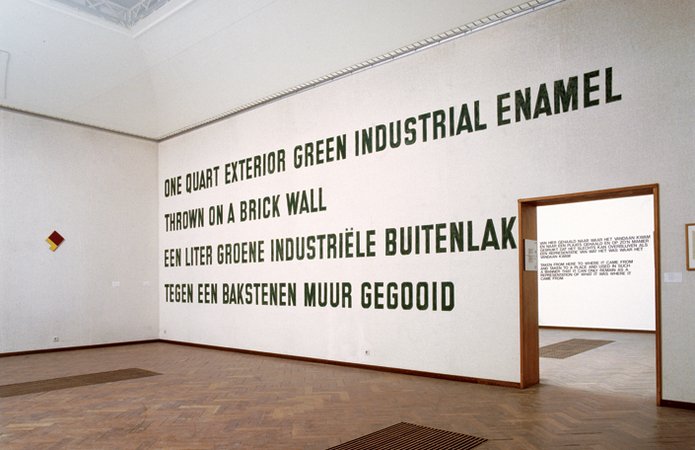

I want to spend a moment discussing the question of materials, from STATEMENTS to now. I think there is both continuity and change. If one looks at STATEMENTS and the work that you did around that time, you selected a rather circumscribed number of materials that are very diverse and yet have a strange homogeneity—materials that are not manifestly industrial such as steel or lead (ie. in works by Carl Andre and Richard Serra), but that are not manifestly pop-cultural like formic or vinyl (ie. Claes Oldenburg, Donald Judd, or Richard Artschwager). You, by contrast, use materials that share a certain subtle commonality, such as nails, pieces of string, cardboard, brown wrapping paper, or plywood. And then there is yet another type, strangely suspended between function and object, as for example the dyemarkers or a flare or firecrackers, which are rather peculiar objects, relating to both the elements of water and fire and to the functions of signaling and sending signs. That is the first group of materials listed in STATEMENTS. Your works at that time approach the limits of ephemerality; they push the definition of sculpture away from its mythical involvement with industrial production, away from the spectacular deployment of industrial materials and processes.

With STATEMENTS I attempted to pull together a body of work that concerned itself with traditional 1960s art process and materials. It was not anti-minimal sculpture; I was trying to take non-heroic materials—just pieces of plywood (nobody thinks about plywood), industrial sanders (everybody has one)—trying to take everyday materials, and give them their place within my world of art, with the same strength and the same vigor, but without the heroics. These works are decidedly non-macho, but they turn out to be the tough guy in the bar.

I wanted people to accept the value of these sculptures because they were functioning as sculptures, not because they were associated with the factory, the foundry, the quarry, the man-things that in those days seemed to mean something. Then I got to TERMINAL BOUNDARIES (1969), which was the next book, the one that did not get published. It is a body of work that has been published in different places that had to do with my being a traveller, that I was a wandering sort of person since I had been a kid. The works in TERMINAL BOUNDARIES were all about materials like quicksilver and lead and all of these other materials that I could use without being heroic, because they were the normal things that people on a road trip would come across.

One Quart Exterior Industrial Enamel Thrown on a Brick Wall, 1968

One Quart Exterior Industrial Enamel Thrown on a Brick Wall, 1968

At the same time, the materials that you chose seemed strangely suspended between an aesthetic of the readymade and that of production. One would certainly not refer to your materials as descending from a readymade tradition; quote the opposite, the emphasize process and production.

But you had to do something with materials. For me it was my approach to dialectical materialism: it was things that you had control over in terms of their production, therefore you would have a sense of their value outside of their monetary value. My work is not Duchampianor anti-Duchampian. I had other concerns at that moment and I still probably do. Duchamp continues to stand as a very important, interesting artist.

If one looks at works such as A SQUARE REMOVAL FROM A RUG IN USE (1969) or A 2” WIDE 1” DEEP TRENCH CUT ACROSS A STANDARD ONE-CAR DRIVEWAY (1968), one sees how the issue of place, another and equally important aspect of your definition of materials, enters the work at a very early moment. Some works are clearly independent of place: very important works of that moment are operating in an undefined place and yet others reflect very specifically on the site and context. So did site, context, and location become central concerns that led to more complex reflections later on?

Well, a wall is not really that site-specific.

But the driveway work is an interesting piece in that it selects a very peculiar detail of functional, vernacular, domestic architecture.

The driveway, again, is not a specific driveway: a driveway is a material.

Yes, but it is a space that is pointing to private property, it points to the home, it points to a location outside of the museum. There is another dialectic that emerged at that time, which is the one of removal and addition: some pieces in STATEMENTS are works that proposed the adding of a sheet of plywood to the floor, for example, or the emptying of a spray-can of paint on the floor, which seems to conclude the eternal dialogue with Pollock. Other works define themselves by the removal of material from existing structures, functional structures. They not only interfere in the visual surface and continuity, but also address another question: to what degree is an object not only defined by language conventions but also by property relations? For the first time they bring the socio-economic factor into the production of the work of art.

That is just what it was: the attempt to reconcile my politics internally—my emotional politics as well as my real politics—with what was becoming my lexicon or my aesthetics, my means of communicating with the world. The funny point is that there was one piece that had to do with Jackson Pollock and it was not that one. It was the piece that was up in Nova Scotia—it was the piece where five gallons of tempera paint were just poured on the floor…

There is something about your usage of the spray-can as both a tool and as a material that makes it rather peculiar and at the same time it refers to a whole range of vernacular and daily usages.

The spray can is an object that contains a whole range of chemical and physical compounds and vernacular and daily usages. It was the looked-down-upon thing, it is about the not-skilled.

Do these strategies and materials not add up to an internal criticism of the false heroicization of even the last layer of industrial materials that was still dominating the aesthetics of minimal and post-minimal sculpture?

Exactly, but that was my role, my own chosen role. I had come from a situation where in order to survive I had to practice, though not necessarily accept, a heroic scale of misunderstanding of the place of the male artist within our society. I then looked at artists whom I really respected, like Pollock, Kline, and Mondrian, who had doubts about this and at the same time did not let that come into their work. They let it into their private life—they had doubts whether they really were David [Roland] Smith… whether they were still the he-men that they started to be, even though they were making art about their soul, even though they were trying to save their soul by making art. I realized that you did not have anything to prove to them any more, that by making art you fulfilled whatever your gender role was, indeterminate or otherwise within the society.

It seems that by the late 1960s you had recognized that the usage of sculptural forms and materials (e.g. the steel cube or metal plate) even in their most rigorously serialized form as in Minimalism, or even in their most scientistic-industrial presentation as in Andrew or Serra, represented a model of sculpture that was largely based on traditional spatial definitions of communicative and perceptual experience. You detached sculpture from its mythical promises of providing access to pure phenomenological space and primary matter by insisting on the universal common availability of language as the truly contemporary medium of simultaneous collective reception.

A universal common possibility of availability. The whole problem is that we accepted a long time ago that bricks can constitute a sculpture, we accepted a long time ago that fluorescent light could constitute a painting. We have accepted all of this; we accept a gesture as constituting a sculpture. The minute you suggest that language itself is a component in the making of a sculpture, the shit hits the fan. Language, when it’s used for literature, when it’s used for poetry, when it’s used for journalism, constitutes an assumed communicative pattern. That implies a belief in God. Without that implication there’s no way that words like love and hate and beauty would have any significance.

If I understand at least aspects of what you say, I would interpret it as a statement about a model of language that precludes both transcendentality and representation, a model of language that insists on its condition of self-referentiality. You seem to be suggesting that the deployment of a particular type of language game that has its origins in the pictorial models of Modernism. I still think, however, that early sound poetry in the context of Dada and Russian Futurism approached an equally critical stance, an equally radical anti-narrative, anti-transcendental, and anti-representational conception of language.

I am not arguing that language is not representational. It represents something. I am interested in what the words mean. I am not interested in the fact that they are words. I am capable of using words for their meaning, presenting them to other people. I hope that the vast majority will read the words for their meaning and that they will place that meaning within the sculptural context of their parameters and how they get through the world. I cannot seem to find the historical precedent for this. Maybe the reason I spend so much time trying to explain that art does not require a historical precedent in order to function as art, is because for many of the things that I’ve found myself doing I cannot find the historical justification.

Let us look at the second phase of your work—even though I am aware that it is problematic to divide it up into phases—announced by the publication of STATEMENTS, a work which not only suggests the possibility of abandoning materials altogether, but also the inevitable resulting reflections on site and placement. With STATEMENTS a new set of presentational problems emerge that you resolve quickly by designing books. The book becomes for a while one of the key carriers of the work, both in terms of its presentation and its distribution.

I still prefer books and catalogues.

Initially at least, it seems there was relatively little design work implied in the presentation of the books. The books seem to emphasize neutrality and conceptualist purity, but there is an explicit denial of traditional artistic book design (e.g. typography and other design choices).

I disagree with that absolutely, totally down the line. Those early manifestations—they are not early, but from the late 1960s, when I had the opportunity to make posters and books and things—are so highly designed you cannot believe it. I mean, take STATEMENTS: there is a design factor to make it look like a $1.95 book that you would buy. The type-face and the decision to use a typewriter and everything else was a design choice.

But still, your arrangement of design features opposed the design culture of the 1920s and 1930s, since the design that you developed in the context of the 1960s Conceptual Art is distinctly different from the heroic moment of avant-garde design. Your book design positions itself in an almost utilitarian context: the book is small, the book can be carried anywhere, the book is totally unpretentious, it does not have graphic intricacies, it is the most functional object imaginable.

I found El Lissitzky’s work fascinating when I was a kid, and then Piet Swart was the next logical thing. My tendencies are towards people who sold themselves on the left rather than people who sold themselves on an authoritative right. But those are my tendencies, those are my politics.

So you define design as a communication that inserts itself within public life, without imposing itself?

It presents itself, it cargo-cults itself, it attempts to entice people to understand that you could talk about universal ideas using simple basic concepts.

But that approach to design among the 1920s avant-garde artists was one thing, whereas in the meantime something had happened to design culture, specifically in America after the Chicago Bauhaus. Here design had been increasingly aligned with ever more rigorous commercial interests and design…

…and power…

Exactly. Design became a power system of the first order, where no modernist benevolence was appropriate any more. So it is in the withholding of a manifest design in the 1960s work that you stage an opposition to commercial graphic design.

It was in opposition to what was considered chic design: that you could have a class association with design when design essentially was supposed to cut across class.

I think it is important to recognize that you work on both tracks. For example, graffito and tattoo seem to be two graphic forms to which you refer quite often as the opposite extreme of design culture, which is as far removed from the immediacy of bodily experience as one can possible get. On the other hand, designers have assimilated your presentation of language and sometimes you are explicitly sought after as a designer.

I seem to have a place within the design community.

But a minute ago we agreed that design in certain ways is also the manifestation of power and interest.

So is art.

Both the tattoo and the graffito are for you fundamentally related to a primary relationship to the body?

I am a sensual artist. I am involved with the sensual relationships of materials. That seems to be the nature of art and I don’t think curtailing that nature is going to make it any more rigorous per se, because essentially it is still about the communications of one human being’s observations to another human being with the intent of bringing about a change of state. At the same time I see myself as working in terms of graffito and in terms of drawing, as if it were a tattoo on whatever part of the body it fits. This is what it should look like; it is an emblem.

Do you remember what you thought when you saw Ed Ruscha’s early books such as Every Building on the Sunset Strip or Twenty Six Gasoline Stations?

Oh that was fabulous, because this was somebody who understood America. This was American art. This was about America.

What was American about it? The focus on vernacular architecture?

No, it had to do with the way Americans saw the world. You had reference points—Mondrian, Pollock, Picasso, anything you want, and they can also be gas stations on Route 66. That is how you knew where you were in the world. I walked into Documenta in 1972 with the intention of making a book and there was my colleague and good acquaintance Ed Ruscha building this structure with Konrad Fischer and it looked fabulous. He just took his books and he hung them up: they want art, they can have their art.

Looking at your book STATEMENTS, one realizes that there are several language games taking place simultaneously. I think that it is only the beginning of an increasingly complex diversity of language operations that you eventually employed in your work. Some of them appear to be purely “descriptive,” they are explicitly directed against the inherently metaphorical potential of language. But there are already indications—and these will become much more obvious later—where the purely process-oriented description of a sculptural project is displaced by an explicit acceptance of a found idiom, i.e., language as a proverb or as a cliché. Is your deployment of the analytic proposition or the performative directed against both visual representation in painting and narrative and metaphor in literature?

I think what I am doing is reasonably pure, even though it might not fit into a language system. Just because I use language, it does not give me the inherent responsibility to be a grammarian, or a linguist.

Could one compare your introduction of language into the field of representation to a situation in the late 1910s, when photography was introduced as a strategy to displace the mythical and feitishistic residue inextricably inherent in painting and sculpture? Photography at that time was an infinitely more communicative medium, as we recognize now that it is within language that ideology and identity are constructed and that it is within language (rather than in volumes) that public communication is possible. I am obviously speaking of your conception of language as one that operates outside of literature and outside of poetry.

This may leave me with egg on my face, but I would say that the introduction of language as a sculptural material as had the effect of incorporating a larger audience into the same questions and the same world as photography did. However, I would also venture that the people who brought in photography were bringing it in for the same reasons that I brought in language. They had no other way to question the answers that had been presented to them but to use this other material. They brought about a revolution. If I was part of this process of bringing about a revolution in comprehension, in making art, and a rational occupation within society, then I would take the credit for it. It is a barricade that I would like to be on and I feel quite comfortable with it, but let us not think that I sat down and figured it all out. Everyone wants to make sense out of the body of an artist’s work but in fact it’s not supposed to make sense, it is supposed to have meaning.

A Translation from one language to another, 1996

A Translation from one language to another, 1996

The most evident case of an artist criticizing narrative and metaphor in the early 1960s was Andy Warhol, specifically in his films. Looking at your own filmic work, I always thought that Warhol must have been an important figure for you. Did you think that his critique of narrativity in film and language should be radicalized and extended into other practices, such as painting and sculpture?

Warhol. That is a real question. Warhol was a real artist. I always had great respect for him, which everybody seems to have always attacked me for. I got a great deal of pleasure from his work.

From the films or from the paintings?

From the work, as I saw it as an oeuvre. If I learnt anything from Andy Warhol, it was how to use a structure to bring about what you wanted, rather than having to use a heavy hand to bring it about. He knew exactly what he was doing, and he knew how to do it, but he was not that big of an influence. Historically, yes, people accepted artists making films after Warhol, but they accepted artists making films before—Kenneth Anger, Joseph Cornell. Warhol was just another person in that line and I think he just stepped into it because he saw that people he admired, like Cornell, were making movies. Maybe I stepped into it because I finally saw people whom I admired, like Godard, like Warhol, making movies, so I just stepped in and made my movie.

You discovered Godard at the same time as Warhol, in the early 1960s?

I saw A Bout de Souffle (1960) when it came out. It influenced me very much.

I saw it recently again and it struck me as the first real work of French Pop Art.

Yes, that’s what it is; the first real work of Pop Art in film.

I always thought that your work was critical towards Pop Art, specifically with regard to the affirmative dimension in Warhol’s work. There is an implicit political radicality in your work that Warhol never had because he is ultimately a profoundly apolitical artist. In that sense you have in fact a much closer affinity to Godard’s project of a critical political film.

I don’t see Andy Warhol as an apolitical artist. I don’t see a conservative acceptance of historical precedent as apolitical: it is extremely political. Warhol’s idols were people like Yves Klein and as such he would have been forced to acknowledge and support things that I would not choose to support and endorse, then or now. That is what a capitalist system is about. They forget to talk about “each to their needs and each to their abilities.” They forget to talk about how much is enough. It seems to be endemic in all classes. But they leave the other part out. I would like not to leave the other part out. That’s the difference. Godard would have liked not to leave the other part out. Fassbinder would have liked not to leave the other part out.

What about the usage of language in your first film, A FIRST QUARTER (1973)?

It is a pretty movie; it is my Godard movie.

What would you say is happening in this film, in terms of my question concerning the traditional narrative framework? The actors are placed in various social and erotic situations and—rather than speaking dialogues—they suddenly pronounce your statements. The radicality of that approach—while indebted to him—exceeds Godard.

That sounds sexy. What if we now take it out of an aggressive stance to radicalize cinema? My major dialogue was existential: I decided to make a mise-en-scène that was closer to where my work could exist, and, in fact, cheapen its value within the society. I was making sculpture to cheapen it to the point that it would infiltrate society and its children’s lives. It had to become a norm within children’s lives. That is all that art is, it is a point of observation for other human beings to notice.

You might not agree, but could one say that A FIRST QUARTER is as distant from Warhol as it is from Godard?

I would absolutely agree. The only thing I learnt from Warhol was that if you wanted to do something, you just pulled it together.

The first difference is that Warhol’s conception of dialogue insists on language in its most common condition, whereas your dialogue is totally scripted and artificially staged. The actors in your films perform very complicated linguistic statements, whereas Warhol prides himself on constructing this endless flow of mundanity.

It seems that in some of the subsequent films and tapes, you criticize your original emphasis on the exclusivity of the linguistic in the work of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Your early work had systematically excluded matter and materials (except for their naming) and the whole plenitude of bodily experience, or the non-linguistic dimensions of subjectivity, narrative and the representation of historical experience had been excluded from your work and from Conceptual Art at large. Suddenly, in works such as DO YOU BELIEVE IN WATER? (1976) there is a repositioning of subjectivity between the linguistic and the psycho-sexual. Here again there is a tension between the erotic performances and the linguistic performance that seems almost programmatic.

It is very programmatic; it is a very structured tape. It is about playing games, about the basis of games. I put in an actor, a homosexual performer, who was nervous around lesbian women for some reason, together with two lesbian women who had never said publicly that they were lovers until then. And that set up tension. What can I say? Nice tape, a little long, but a nice tape. I will be damned if I ever wanted to exclude any sensual function from art. I am just an artist, you know, I do not have to be right all the time. I am not giving out medical prescriptions to people and I am not flying an airplane, I am just this person putting things in the culture.

Another important example in that context would be the so-called pornographic videotape from 1976, entitled A BIT OF MATTER AND A LITTLE BIT MORE where you confront the viewer with actors who pronounce your work and at the same time perform sex acts—what might be perceived as the opposite of a linguistic operation.

It is not grammatic but it’s not anti-linguistic. The porn tapes were done for political reasons. They were done because the United States government was putting people who made pornography in jail. Now I do not get off on pornography, but I do not like them putting people in jail just for making pornographic films.

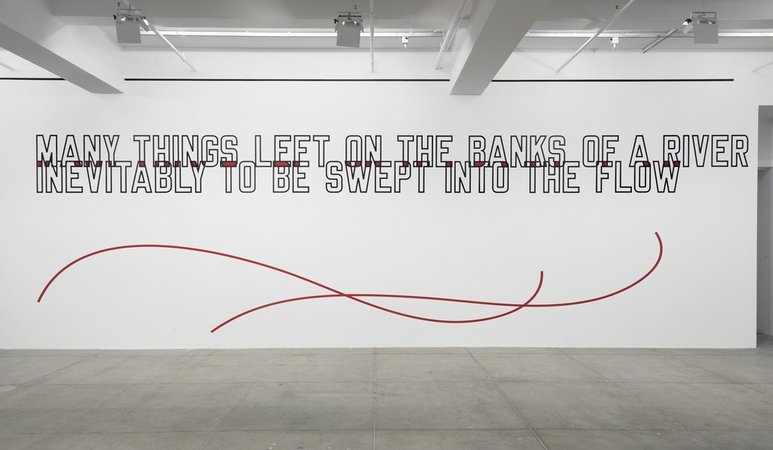

MANY THINGS LEFT ON THE BANKS OF A RIVER INEVITABLY TO BE SWEPT INTO THE FLOW, 2014

MANY THINGS LEFT ON THE BANKS OF A RIVER INEVITABLY TO BE SWEPT INTO THE FLOW, 2014

We talked about the various language models that are already evident in STATEMENTS, but there is another language model entering your work later, where you insert statements that explicitly refer to specific historical conditions. I am thinking of the installation in Vienna for example, SMASHED TO PIECES (IN THE STILL OF THE NIGHT) (1991), where the statement itself seems inextricably bound up with the historical context of the city and the site where you installed the work—even though one can read the statement in a variety of other ways.

It found an immediate metaphor when it was placed within that structure. If they have been objectified culturally, then historical references are usable as materials, because that is an objectified cultural entity the same as time and sound and remembrance.

Would you really say that all the resonances of these works with their sites are as uncalculated as you claim now?

When I was invited to Vienna, I was involved with the sound of things in the night and the sound of things in the day because I had been working through projects where I had been awake all day and all night. Things sound different at night from in the day, especially in cities…

Can one really read the work, when installed on the Vienna Flakturm, outside of the Holocaust history of the city?

I am interested in the difference in sounds between night and day. The offered me this Flakturm, this anti-aircraft defense tower; I chose that piece to put on it. I knew damn well it had a metaphor. It was the work that was coming out at the time, maybe at that moment I was thinking about those things. Art is fabulous because it starts off as one thing and becomes something else for somebody. That is its whole function. In fact this is not the metaphor of this particular work. If I put it in another context, which I often do as you know, it has a totally different metaphor. You put that piece in the South Pacific and all night you will hear coconuts falling, all day you hear coconuts falling.

Your work for Skulptur Projekte in Munster in 1997, DRY EARTH & SCATTERED ASHES… could be another example. It is by no means the only piece that focuses on those questions concerning the relationship between text and material and between text and placement. Would you want to differentiate the function of writing from the function of the object in your work, since the writing does not in all instances take on a material, sculptural form of presentation; it can also take on a merely typographic, scriptural form. Are there specific criteria according to which you decide that one work should appear solely in writing and another work appear in a material structure?

The criteria are totally non-hierarchical. The work gains its sculptural qualities by being read, not by being written. Each work itself is the result of material experimentation, material building, translation—translation into language and then the presentation is whatever affords itself. In Münster, I was in a dilemma, I was confronted by a social paradigm that required that I question what is public sculpture, because in fact the carnival atmosphere of these shows does not necessarily have anything to do with public sculpture. So I used the steel plates that they put over holes in the ground. But there is no real hierarchy about how a work is presented. If somebody wants a tattoo they get a tattoo—it all has to be basically the same to me.

Does this mean that the same statement that was shown in Münster could theoretically be shown somewhere else?

It was initially shown in Munich and there is a little book of prints that were also made into posters to be given away in Munich.

So the work was neither specific to its context nor specific to its presentational and distributional support system?

It was not specific to Münster, the work is never specific to any place. I have a feeling about work that one does, because it is the dance to the music of your time. That is the problem for me with work that is specific and journalistic: it serves its function in its first performance, but it is never allowed to live a full complete life as a work of art, which is to find its own metaphor. I mean, the Giacometti state-set The Palace at Four a.m., (1932-33), found its metaphor in the Museum of Modern Art—that made more sense to emerging New York City kids than it did when it was shown for the first time—it had no metaphor there. It was very important for me as a young person. It was not about alienation. It was about survival, very much like my youth. Forty-second Street and places like that at four o’clock in the morning. Coming out of the movies having seen Général de la Royère, I began to understand what people were trying to do—they were trying to build a mise-en-scène.

Let me put the question in a different way, or expand on it: what language model underlies your critique of metaphor as a pre-established fixed meaning, as a pre-established system? Are you establishing with your own means a critique of language that would have parallels in poststructuralist deconstruction, from Lacan to Derrida?

It is pre-Derridian and it is certainly non-Freudian. The argument between Piaget and Chomsky provided me with my definition of the language model. My discovery of the original Chomsky in the Mouton edition as a kid helped me comprehend that there was a whole understanding of generative grammar and a kind of genetic imperative. Piaget was dealing with shell-shocked children; his realization was that children are in need of “nomering” something, and in “nomering” it, they do not always have to accept why it is called pomme de l’air or pomme de terre—an apple is called an apple because the name apple is written down inside it. All children determine that, so why do artists have to be made into romantic souls because they bring the soul out of the material and make the material acquire its real name?

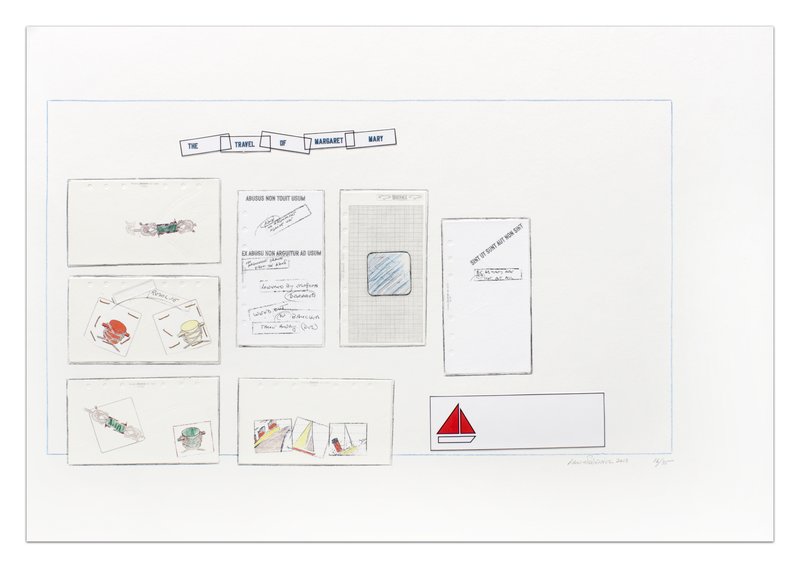

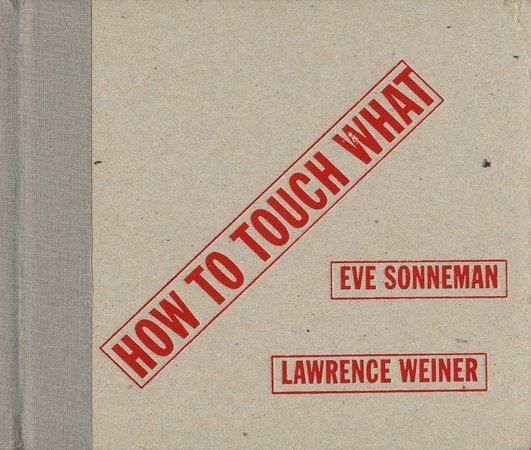

Lawrence Weiner and Eve Sonneman, How to Touch What, 2000

Lawrence Weiner and Eve Sonneman, How to Touch What, 2000

I was wondering whether we could establish a certain continuity between the film work and your recent music. There is a similar juxtaposition between your statements and the given system, in this case the peculiar lyrics and the specific musical conventions, ranging from reggae to country western. Are they, like Pop Art, addressing pre-existing systems of representation? Could one say that you use musical structures in the way that Roy Lichtenstein used a comic book structure as the point of departure for a painting?

The entire concept for me of using a musical structure as a means to present work is not new. I made my first record, SEVEN with Pierre-Yves Artaud and Beatrice Conrad Eybesfeld around 1972. Later I worked on the soundtrack for my film A FIRST QUARTER with Dickie Landrie and on soundtracks with other musicians like Peter Gordon. Putting the work in the context of the music cheapens it and at the same time heightens the fact that it has a relevance to our society. It is not just that it can fly that makes it interesting, it is the fact that it can walk as well, and that is why I use the songs. I have retained the privilege of being an artist who makes films, an artists who makes music. I do some arrangements, but essentially I am a lyricist for musicians. You have to write lyrics that place the work within the context in which you would like it placed. Again, without a metaphor.

What happens, however, is a radical transformation of the musical structure. One model that comes to my mind would be the Situationists’ détournement. That really seems the closest comparison that I know: using an existing structure of signification within the culture and overturning its reading.

No, I don’t turn it upside down. I take it out of its context. I don’t say this in the lines of Chuck Berry but that this is something using what he would use, but with an artist collaging something in. It is not done in a Situationist manner, it is not the détournement.

What about the CD you did with Ned Sublette, MONSTERS FROM THE DEEP (1997)?

I wanted to deal with a spectrum of music, a reconstructive aspect that I had been interested in from early techno, but at the same time I did not want to find myself doing retro things. So we went and found Kim Weston—who really sings like that to make a living—J Otis Washington, Red Fox, Lenny Pickett. This is the music they play every day of their life. We gave them a slightly different rhythm and different words.

What interests me here is the relationship between your writing as work and your writing of the songs. Can we talk about the content of the lyrics versus the commonality of the music? Why do you inscribe these rather esoteric lyrics into popular forms of music and how are these songs different from your other writing, if at all?

You mean the work? They have nothing to do with the work even though often the songs will incorporate works.

How does that relation function then?

They are shown within the context. Look at it as a mise en scène—they set the mise en scène for the previous collection of work.

You keep using the term mise-en-scène and I do not think that it is as clear as you imagine it to be.

It is the stage-set. I made a small-scale sculpture edition in Japan, STAGE SET FOR THE KYOGEN OF THE NOH PLAY OF OUR LIVES (1995). It is a stage set for the Kyogen that has Madame Butterfly talking about contemporary problems at this particular moment that never existed before. They do that in the middle of the Noh plays—they have little political things that they hit the drum for and then they make these jokes.

The work as language is then inscribed into the song as a given, pre-existing language structure?

As a given language structure that relates to something else. The piece from Münster appears in a song in MONSTERS FROM THE DEEP—it is just presented within that other context. Everything has a double context, you know—a Carl Andre brick sculpture can also be used to stop the levee from going over the side. A brick remains a brick. There is no question of transcendence. I don’t see any reason why if they can take a work of art and put it on a record cover, you cannot put it inside the song.

But when you say that the songwriting has nothing to do with the work, I still think that this distinction between statements as sculpture and “mere” lyrics for the songs is not as easily made, at least not from the outside, because the transitions between the two seem very fluid.

It is collaged.

So you would argue that the texts of your works inserted into the lyrics function as sculptures?

The works are always sculptures, so what everybody calls texts and sentences and wall-tattoos and this and that—it is not for me to give them a name, it is art—are functioning as art. That was my job as an artist, to say that was art.

So when Kim Weston or Red Fox now sing your famous STATEMENT OF INTENT from 1969, when they now sing it in their different intonations and one flashes back to 1969, when the STATEMENT was presented as a radical promise, does it not sound as though the contemporary musical presentation had acquired a certain farcical dimension and that you cannot take that original revolutionary aspiration of the STATEMENT OF INTENT quite as seriously any more?

Yes, but then if you go from being a revolutionary who will only fight in causes they believe in to being a soldier, you cannot really consider yourself a revolutionary anymore, can you? You may as well do it with some aplomb. Why, in heaven’s name, when something is taken off its pedestal, why does it have to be less important than it was before?