Interviews

Jay McInerney, The Art of Fiction No. 231

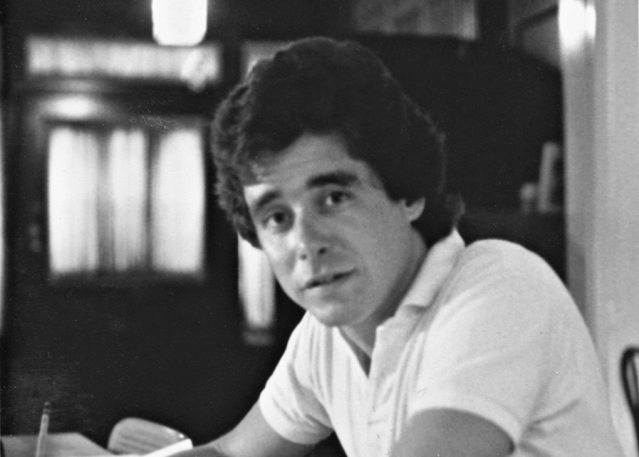

Jay McInerney at work on Bright Lights, Big City, 1983.

Few novels stand for a place and time the way Bright Lights, Big City stands for downtown Manhattan in the 1980s. Narrated in the second person, Jay McInerney’s first novel tells the story of a young fact-checker, at a magazine very much like The New Yorker, who loses his way in the cocaine-fueled nightclub scene. From the moment it appeared as a paperback original, in 1984, Bright Lights established McInerney as a chronicler of New York’s bright young things. In his six subsequent novels and numerous short stories, he has broadened his scope and his canvas, but he has never taken his eye off his adoptive city or the intersection of the literary world and that city’s flashier precincts. His recently completed novel, Bright, Precious Days, is the third in a trilogy that follows the fortunes of book editor Russell Calloway and his wife, Corrine, as they struggle and thrive from the late 1980s through the 2008 recession.

Born in 1955, McInerney spent his childhood moving from suburb to suburb in the U.S., Canada, and England. His father was an executive for a New England paper company and, in McInerney’s words, a “Nixon guy.” His mother, a housewife, was active in liberal charities. (There is a children’s center in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, named in her honor.) Sharing her political passions, her son, a “would-be hippie,” was drawn toward social activism at Williams College, then as now filled with investment bankers in training. In 1977, after a stint as a local reporter in New Jersey, McInerney received a fellowship to teach in Japan, where he hoped to write the Great American Expat Novel in the style of Robert Stone or Graham Greene. Notes in hand, he returned to the U.S. three years later with his first wife and took a short-lived job as a fact-checker at The New Yorker. But he made his first mark on the literary world with a story in the Winter 1982 issue of The Paris Review, which would become the first chapter of Bright Lights.

I spoke with McInerney three times in February and March of this year. We met in the Greenwich Village apartment he shares with his fourth wife, Anne Hearst McInerney. Their art collection dates from the moment they each arrived in New York: works by Cindy Sherman, Keith Haring, and Caio Fonseca share wall space with photographs of McInerney’s literary heroes Faulkner, Joyce, and Kerouac. Once we turned off the recorder, our conversations continued over a meal in the neighborhood and a bottle or two of very good wine (since 1996, McInerney has moonlighted as a wine critic for House & Garden, the Wall Street Journal, and Town & Country). He is known, and much appreciated, for bringing his own hamper of bottles to black-tie benefits around New York.

Now sixty-one, McInerney has lost none of the energetic volubility that made him one of the most quoted writers of the mideighties, when he, Bret Easton Ellis, and Tama Janowitz were collectively known, by critics and gossip columnists alike, as the “Brat Pack.” Although he enjoys telling a good story—especially if it shows him in a slightly comical light—it is notable how often our talk turned to other people’s fiction, either the classics that formed his sensibility or new novels that piqued his interest. (Janice Y. K. Lee’s The Expatriates was on the breakfast table.)

—Lucas Wittmann

MCINERNEY

Between my duties at The New Yorker and my nightlife and everything else, I wasn’t getting much writing done. But one morning, shortly after I got fired from The New Yorker, I was home, sleeping late, when I got a phone call from Gary Fisketjon saying that Raymond Carver was coming in to visit me. And I thought it was a joke, and I hung up. About twenty minutes later, my buzzer buzzed, and there was Raymond Carver at my doorstep. It turned out he was in town for a meeting with his editor, Gordon Lish, and didn’t have anything to do until his reading at Columbia that night, so Gary and Gordon sent him down to see me—because they had work to do and I didn’t. And because they knew I was a big fan. Oddly enough, it was the morning John Lennon was killed. I’d just heard the news on the radio. So it was a strange day. We just started talking and really hit it off.

INTERVIEWER

What was your conversation like?

MCINERNEY

We talked for hours, mostly about books, about fiction. The cocaine I brought out to help break the ice certainly lubricated the conversation. We ended up being hugely late for his reading at Columbia that night, and he read the story “Put Yourself in My Shoes” exceptionally fast. I think eventually he determined that there was something in me that might be worth . . . saving. And also that I better get out of New York if I intended to become a fiction writer. Afterward, he wrote me a letter suggesting that I apply to the graduate program at Syracuse University, where he was teaching.

INTERVIEWER

What was he like at this time?

MCINERNEY

He was a big, bearish man but soft-spoken. And he spoke in a very hesitant kind of way, as if you could just hear him thinking out loud. There was a fragility about Ray then, because he had recently stopped drinking, after almost a lifetime of abusing alcohol.

INTERVIEWER

What did you learn from him?

MCINERNEY

He said you have to write every day.

INTERVIEWER

Even when he was at the height of his drinking, he was trying to do that?

MCINERNEY

He was relentless about that. And I think he was right. You can’t always write well, and sometimes you can’t write at all, but if you’re not there at your desk trying, then you won’t succeed. Before then, I had thought of writing as something akin to divine inspiration. I would wait for the muse. Turns out you have to be dressed and ready for the muse or she will never come.

To read the rest of this piece, purchase the issue.

Summer 2016

No. 217

Fiction

Alexia Arthurs, Bad BehaviorBonnie Jo Campbell, Down

Rachel Cusk, Freedom

Rafil Kroll-Zaidi, Lifeguards

Gerald Murnane, From Border Districts

Benjamin Nugent, The Treasurer

Interview

Jay McInerney, The Art of Fiction No. 231Dag Solstad, The Art of Fiction No. 230

Poetry

Adonis, From Elegy for the TimesDanielle Blau, I Am the Perennial Head of This One-person Subcutaneous Wrecking Crew

Eliza Griswold, ISIS & Friends

Golan Haji, Another House

Devin Johnston, Two Poems

Jana Prikryl, Ontario Gothic

Frederick Seidel, To Mac Griswold

Monica Youn, Four Poems

.jpg)