Opinion

Kenny Schachter Goes for a Swim in the Summertime Art Market and Gets Stung

After a fateful dip in the waters off Ibiza, our plucky columnist learns that jellyfish and art dealers have a lot in common.

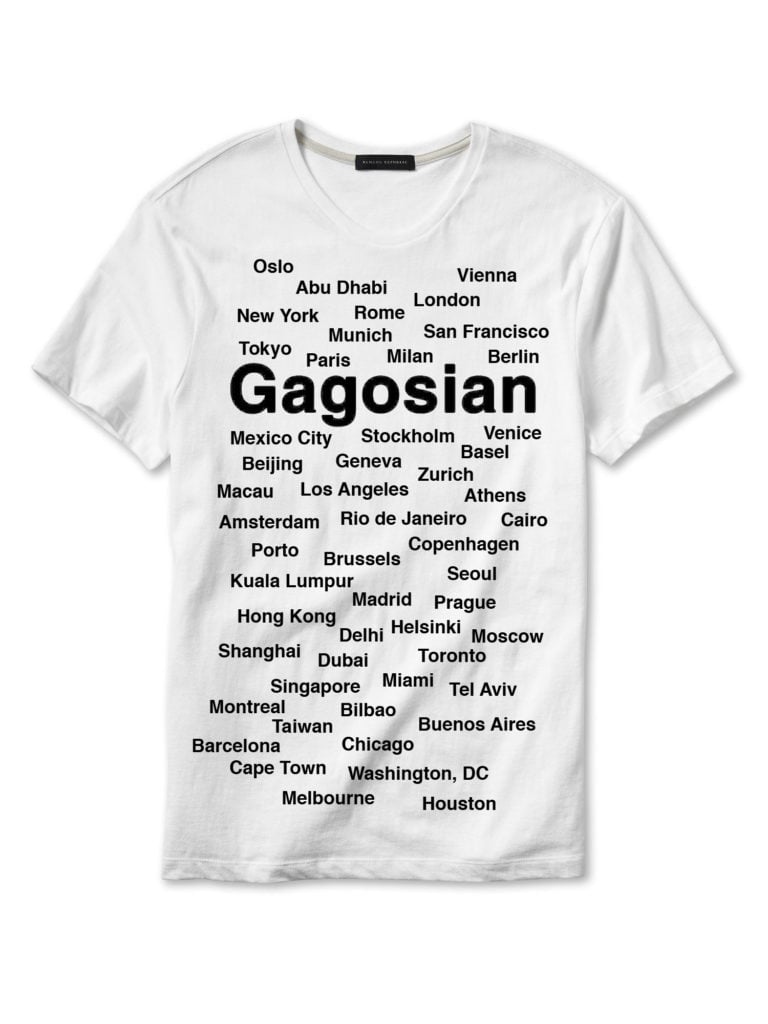

As much as global warming has disrupted the traditional cycling of the seasons, the 24/7 maelstrom that is the art market has also had an impact of its own: it has eradicated summer as a time of hiatus, at least for those in the trade. Even on the chilled-out Spanish island of Ibiza, there were plenty of art dealers on hand, cagey and cunning as ever. During the 1930s, Walter Benjamin, Raoul Haussmann, and Tristan Tzara were among the many creatives and intellectuals that sought solace at this sandy Mediterranean retreat. It was, and still is, a place of freedom in all senses (for better and worse), replete with a storied aura of special energy, if you believe in such things; I’m not sure I do. But since Pasha and Amnesia, the mega-nightclubs with capacities of 5,000 each, only launched in the mid 1970s (to be followed by many others), there must have been something more than the ready supply of MDMA that lured vacation-goers.

Ibiza has always been a hippy hangout and thus faced very little brand-saturated over-commercialization (aside from the clubs); most of the land was restricted from development in the past, and has become more so under the leftist-led political party, Podemos. There are more shamans and healers on hand than in Los Angeles, even—one morning I came down for coffee and found my wife jerry-rigged to an improv IV bag hanging from the chandelier over the dining-room table, mainlining vitamins.

Ilona on the drip. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

On a Friday evening (if 2:30 am can still be considered night), I was semi-coerced to attend the “Music On” party with DJ Marco Carola at Amnesia. I lasted ’til 7:30 am, the horror. The club was peopled with a thick layer of middle-aged, well-off white men who seemed to relish falling off the deep end after having spent years beavering away to be able to afford behaving like a child again (and dressing the part). The positioning of the private tables above the dance floor is like the floor plan of an art fair—there is a hierarchy for the coveted slots. Shimmying next to our prime perch was none other than art dealer Jude Hess; I couldn’t resist seizing the opportunity to shout over the juddering ruckus about a Judd I had on offer.

Body tattoos in Ibiza. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

I was handed a reddish pill I assumed was MDMA, which I proceeded to flush down the toilet; said to increase empathy and euphoria, it’s akin to an emotional subsidy. I’m not saying I would have passed a urine test the following day, but the last thing I need or want is a drug that makes me indiscriminately like people. I’d be out of a job. But it did occur to me to make my own pills—to try and outdo Richard Prince, who recently made his own strain of marijuana—and then hand them to clients, especially disgruntled ones. After all, ecstasy already comes in designer colors and shapes to connote different variations, just like Jeff Koons editions. I’d call it KenDMA. Anyway, I noticed that what passes for music played by star DJs—who are celebrated like deities—sounds more like the commotion heard at a construction site, or from a reversing truck. The incessant throbbing bass pauses, restarts, then repeats; each time the crowd goes ecstatic, as if surprised. With all the drugs consumed (and lack of short term memory) they probably were.

After a peaceful family lunch—or as close to peaceful as the Schachter clan can get—on the nearby island of Formentera, the smallest of the Balearic Islands (Majorca, Minorca, Ibiza, and Formentera), we jumped in for a leisurely dip. (I work like a dog and swim like a turtle.) Of course, I was stung by a jellyfish. It felt like a battery charger clamped onto my flesh had been blasted with a jolt of burning electricity. After I let out a commensurate scream, it was the fastest I’ve ever seen my 21-year-old move in retreat. Increased climactic conditions have resulted in a jellyfish plague, and the Pelagia Noctiluca, or mauve stinger, indigenous to the area are classified as among the harshest, under the heading ‘highly irritating.’ Like my writing. As anxious as I ordinarily am, now I’m scared to swim in a pool.

Kenny’s jellyfish-inflicted wound. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

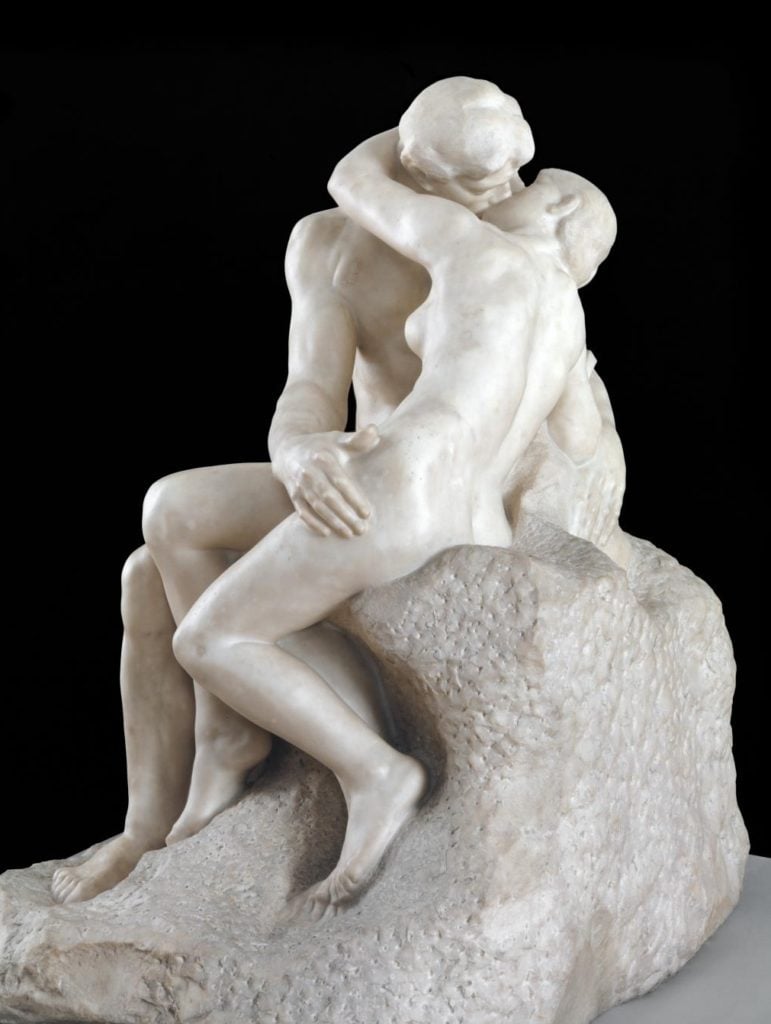

It made me think that art dealers are really more like jellyfish than the predatory sharks to which they are popularly compared—after all, sharks violently devour their prey, and dealers can’t afford such totality, requiring the opportunity to bite again (and again). And we mustn’t annihilate our enemies, lest another deal may arise. As a friend said, “business is business and liquor is liquor”—i.e. it’s not wise to mix (too much) business and friendship. Just as in the ocean, I’ve found out in art (the hard way) that you must always proceed with caution and swim at your own risk!

The Parra & Romaro Gallery in Ibiza (and also Madrid) is a family run enterprise headed by Guillermo Romero Parra, whose parents started the business by dealing in secondary-market Spanish art in the 1980s. This is his fifth season in Ibiza and, with a “rigorous program between the boundaries of conceptual and minimal art,” he doesn’t make it easy for himself. But his focus and dedication is heartening, as was the fascinating Nancy Holt show with drawings starting at under $20,000 (a deal!). Holt is known for her land and installation art, and once collaborated on a video with Richard Serra in the 1970s.

Nancy Holt at Parra & Romero. Courtesy of the gallery.

As the accordion playing, stilt-walking, fire-eating, poker-playing, and street-busking billionaire founder of Cirque du Soleil, Guy Laliberté also operates two spaces on the island under the banner Art Projects Ibiza/Lune Rouge. In collaboration with Lisson Gallery, there was a ho-hum Cory Arcangel exhibit in tandem with the artist Olia Lialina (also underwhelming). Arcangel, called a “post-conceptualist,” whatever that might be, had a few of his popular color-gradient Photoshop photos sell at $85,000 and $350,000, and had a pair of flip-flops on offer that read: “FUCK NEGATIVITY.” I’d need to retrieve the little red pill I tossed to appreciate those. Laliberté’s estate was closed to the pubic this year, after hosting a Jenny Holzer sculptural show on the grounds last year. So much for chill.

Cory Arcangel at Art Projects Ibiza. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

The perfect transition from Ibiza was a brief stopover back in LA. I didn’t see any celebrities (because I don’t Soul Cycle) but I did eat a celebrity tomato (“cultivar is a hybrid that produces long fruit-bearing stems holding 20 or more very plump, robust tomatoes,” according to Wiki). You can daily track earthquakes in California, where, as of Tuesday morning, it appeared there were 33 in the past 24 hours; 176 in the past week; 785 in the past month; and a total of 8,154 in the past year. Nevertheless, LA continues to grow at a torrid pace, a testament to human resolve, foolishness, or both. If there was a quake in central LA, who wouldn’t be up for a little looting at The Broad

This time of year, LA is crawling with art-worlders ranging from the Nahmad clan to European and Middle Eastern collectors galore. Most can be found in the lobby of the Beverly Hills Hotel—owned by the Sultan of Brunei fitting enough, and formerly Ivan Boesky’s. I awoke in my room to find a fireplace blaring; it took an engineer 20 minutes to find the light switch that controlled it. I still have a hard time adjusting to indoor fires…. When I asked the concierge directions for a meeting, he turned his head sideways like a confused dog when I said I’d be walking. I should have heeded his concern—crossing the monstrous intersection in front of the hotel was as complex as geometry. I was invited to a dinner where one guest drove three doors down the street to eat, another brought up Scientology to the agent of an adherent, and the values of the flats vs. the hills of Beverly Hills were debated.

A Jon Pylypchuk sculpture. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

Jon Pylypchuk is an eclectic sculptor and painter whom I’ve admired for ages, and had the opportunity to visit via an Instagram intro. His openness and generosity of spirit was reminiscent of the 1990s New York art scene I started out in, when a sense of community was in the air (and innocence, to some extent); in fact, I don’t think I’ve experienced it since. Pylypchuk frequently gives over portions of his studio to emerging artists—when I visited it was Luis Flores—and operates a gallery, Grice Bench, with a partner who didn’t want to be named. One of the gallery’s artists, Christina Forrer (a weaver of wacky wall hangings), has since been picked up by Luhring Augustine Gallery, but that does nothing to besmirch the purity of intent between Pylypchuk’s studio and gallery practice.

The artist Luis Flores. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

Born into another art-dealing family, private dealer Niels Kantor has operated public galleries, as his late dad did before him for years. Residing in the former family home across from the Beverly Hills Hotel, Kantor built a miniature gallery in the house complete with cement floors, a simulacrum of a space made to measure for Insta-only shows—a first, as far as I know.

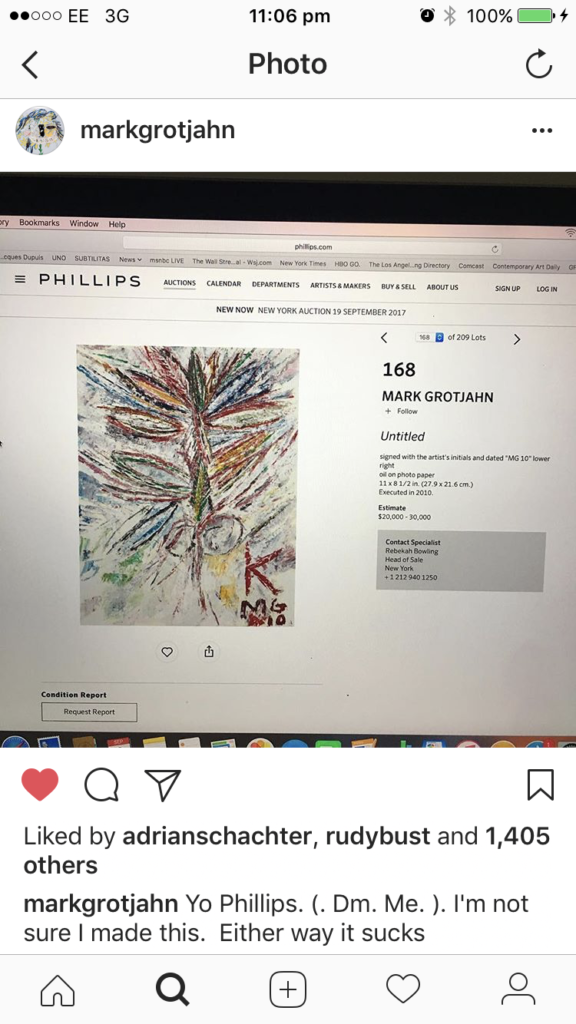

Here are a few LA stories. A museum board member called Mark Grotjahnthe world’s most successful outsider artist in history, having met the naïve artist fresh out of art school, when Grotjahn’s first words to him were: “I will be a million-dollar painter.” He was wrong—he’s the $16 million man (for some odd reason). When it rains, it pours—now the world is tripping over itself to “collect” the paintings of his wife, Jennifer Guidi; aboriginal-esque, formal, Arte Povera in feel, they are decorative mark-making that looks nice and has a fine pedigree. Ca-ching. My pal also mentioned that his museum had a strict no-collect policy regarding a certain young, well-known, ubiquitous artist, even for proffered donations. And Venus Over LA let go its staff and appeared to subsume the Lower East Side emerging gallery Ramiken Crucible in its entirety, hiring its dealers and importing them to the city of angels. I guess like Victor Kiam, who famously loved the Remington razor so much he bought the company.

A LA pool party with a masked Chinese “influencer.” Photo by Kenny Schachter.

My summer was bracketed by trying to secure a guarantee for a work in the coming London October contemporary sales; last time I checked they’re still having them despite the fact that Christie’s bowed out of the June proceedings—a first since they began selling contemporary art at night. (London is pretty down at the moment, I feel.) One contract specified that the auction house could claw back the advance of the guarantee within a certain period: if London was declared a disaster area, if the Dow Jones average declined by 20 percent, if stock-market trading was halted, or if any auction sales results were equal to or below 50 percent of the presale low estimate. What if it rains in Spain, does that give rise to a cancellation clause? In the heat of negotiations between two houses, a Phillips associate whom I previously helped with career advice wrote me this peach of an email:

“You’re the loser here (and coming across as a total prick). If you’re not prepared give our guarantor more time, to raise their offer, then you will not get the deal that you wanted from us. Going forward don’t waste my, and my colleagues time, unless you are prepared to deal seriously—and not pathetically crumble to other pressures. Best luck with Sothebys [sic]!”

Lovely! I sold it privately.

This kind of art-world sting makes me long for Ibiza, which may be the land of clubs gone wild and horrible full-body tattoos, but the natural beauty is unparalleled and the seafood for lunch and dinner was likely swimming earlier in the day. (My actual jellyfish wound is still itching as I type nearly a month later, but I survived, got out with my hair and molars; what more can you ask?) And with works sold by artists from Zaha Hadid to Rachel Harrison (to my kids), both privately and to museums, the “Nuclear Family” show at Ibid Gallery was another LA story with a happy ending. Stay tuned for the sequel(s) beginning in November at the 021 fair in Shanghai.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE