| The Kicker |

LIFE LESSONS. Today El País has an expansive interview with architect Elizabeth Diller, whose firm handled the Shed and the most recent MoMA renovation, among other notable projects. While eating “a soft-boiled egg with a teaspoon,” Diller talked about her childhood, taking risks, and teaching. She’s a professor at Princeton , and she shared one method that she's used with students. “When they had something half-developed, I changed the assignment and asked them to adapt it,” she said. “The exercise destabilized them, they had to rethink everything. They hated me. But they learned a lot.” Prospective pupils: You have now been warned. [El País] |

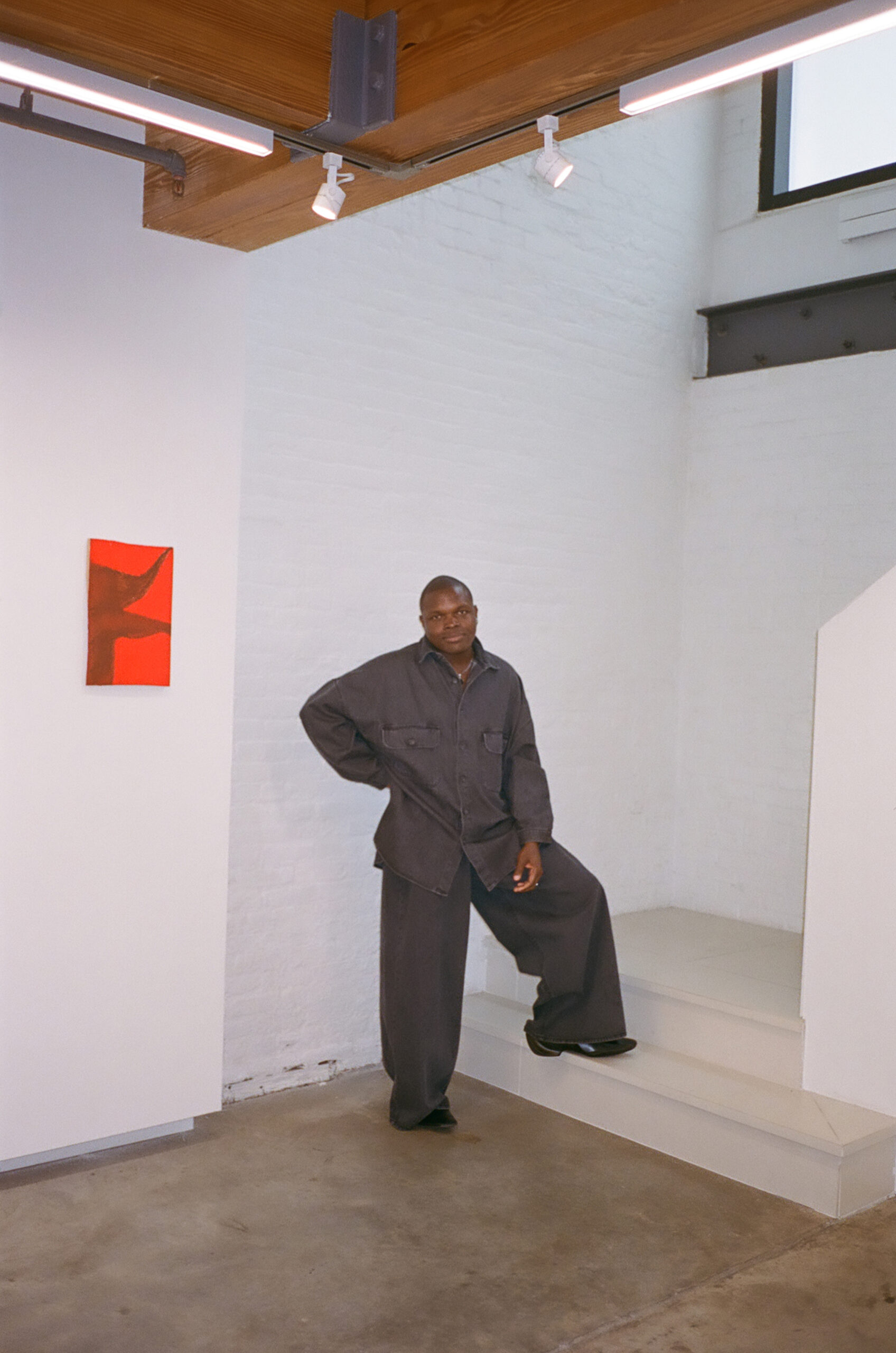

Elizabeth Diller, architect: ‘Austerity is an excuse to avoid experimentation’

At the helm of New York City’s contemporary architectural movement, this daughter of Holocaust survivors has been reinventing spaces in Manhattan

The Broad, in Los Angeles. The Shed, in New York. The Institute of Contemporary Art, in Boston. With her partners — Ricardo Scofidio, Charles Renfro and Benjamin Gilmartin — Elizabeth Diller, 69, has designed some of the most unique museums of the 21st century. The architect — who was born in Lodz, Poland, to Holocaust survivors — has also been busy crafting New York City’s latest look.

Diller came to the United States by boat as a child, growing up in the Bronx. She recently stopped by Barcelona to attend the Smart City Expo. Over breakfast in a five-star hotel — eating a roll and a soft-boiled egg with a teaspoon — she sat down with EL PAÍS for an interview.

Question. Would you be able to make it to New York today, like you did as a child?

Answer. No. In 1959, it was possible to start a new life in the Bronx. [But today], who could pay the rent? Most of the artists are now gone.

Q. What do cities lose when they lose their artists?

A. Someone who tells them the truth. When we did The Shed [a cultural center in Hudson Yards] with the Rockwell Group, we wanted to recapture the idea of New York as a center of cultural production — not as a place frozen in time.

Q. Did you take unnecessary risks while building The Shed? Why make a mobile building?

A. A theater is in continuous transformation. Why not move it a bit more? The transformation of an exhibition hall into an auditorium had to be something simple, electric. [Before], to save money, they did it manually. Today, the result is clumsy.

Q. Is risk related to intellectual growth?

A. Challenges empower me. Comfort makes me sleepy. I don’t understand taking risk for the sake of risk — but I do understand the reward after risk. It’s a source of energy, life and change. Many times I knew that I would lose bids if I took risks, but I didn’t know how to do anything else.

Q. You’re also a professor at Princeton. Do you teach risk?

A. I unteach the students. I release them from what they have learned, so that they can think. Preconceptions can limit thinking. I ask them how to deal with the obsolescence and speed of the world with something as slow as architecture.

When they had something half-developed, I changed the assignment and asked them to adapt it. The exercise destabilized them, they had to rethink everything. They hated me. But they learned a lot.

Q. You’re one of the architects behind the New York of the 21st century. And you came to this city when you were five-years-old.

A. My parents had to say goodbye to their life. It was traumatic. They left their past in Poland. Also their comfort: there, they had money. But they came to a place that was seen as the land of opportunity. Traumatized by the Holocaust, they wanted to flee as far away as possible, so that their children could have a life.

Q. Did you end up having it?

A. Well… they were always afraid, but I studied what I wanted.

Q. Did you have a religious childhood?

A. In my house, religion was a cultural issue, not a spiritual one. My father was Czech and my mother was Polish. He ran textile factories in Lodz. Neither he nor my mother had studied [in university]. He was an enterprising man. He spoke languages. He learned English shortly after arriving in New York. He was a survivor. My mother, on the other hand, never adapted. She spoke to me in Polish — thanks to that, I still speak it. Sometimes, I think it was my fault: that by talking to me, she didn’t learn English.

Q. Your parents left Poland in 1959. Were they fleeing Nazism?

A. There was a lot of anti-Semitism, even after the war. Even if my father wasn’t religious, he was Jewish. My father’s nine brothers and my grandparents died in concentration camps. In New York, as a child, I ran away from that pain. Today, I regret not having asked more questions. But in my house, everyone wanted to forget and start over.

Q. Your brother was 13-years-old when you left.

A. He wanted to forget. In Lodz, he was bullied for being a Jew. Here, he was able to study engineering. Today, he doesn’t identify as a Jew.

Q. And you?

A. It depends on who asks.

Q. So you have a flexible identity?

A. A survivor’s identity. I feel European. But not particularly Polish. And, at the same time, I’m very much a New Yorker. I believe that my ethics and my sensitivity towards what’s different come from my parents.

I never felt completely American, whatever that is. I’m used to change. I’m interested in repairing things. I don’t know to what extent that contradicts my parents’ decision to run away from problems. But I’m like that. In my work — and in my life — I confront and try to change things. Children run away from pain. But then, you realize how you end up carrying that guilt.

Q. What were your parents like?

A. My parents were hyperprotective. I think that loss made them fearful. The damage one receives grows over the course of a life.

Q. What did your parents do when they arrived in New York?

A. They started from scratch in the Bronx. My father carried sacks of fruit. My mother cleaned offices. At the end of his life, my father fulfilled the American dream of seeing his children go to university. He ended up running a hotel. We never felt poor.

Q. And in this context, you decided to become an artist.

A. What worried my mother was that she didn’t want me to be financially dependent on men. She was obsessed with this.

Q. And then you go ahead and fall in love with your teacher.

A. That also happened. But my mother always supported me. She asked me if I wanted to study architecture. When I said no, she then insisted that I become a dentist! She wanted me to have a profession. So, I studied Fine Arts and, after two years, I transferred to Architecture. That’s where I met Rick. He was my crush.

Q. You were 23 and he was 42.

A. It’s even more shocking that we’re still together. We’ve dedicated our lives to architecture.

Q. It seems like you’re the strong one in the relationship.

A. Because I talk a lot. I could never have done what I’ve done without him. He’s a great teacher and people love him.

Q. Do you have children?

A. Ric has children from a previous marriage. We didn’t have any. Sometimes, I think about it. I’ve spent my life postponing it: it’s always next year and, in the end, that year hasn’t arrived. I’m happy with the life I have. How can you know what would have been better? Do you have children?

Q. Two.

A. Did you stop working?

Q. No. I think I would have gone crazy.

A. Ric had four. If I had asked, he would have agreed to have another, but I didn’t want to force it. The only one who pressured me was my mother and… I didn’t listen to her.

Q. Your mother pressured you to have your own life, but also to have children!

A. For her, it wasn’t contradictory. She wanted me to learn English and she spoke to me in Polish! That’s why, when she died, I sank.

Q. Was it difficult for you to create a body of work that lasts?

A. Building wasn’t our obsession. Ric was tired of architecture. And I was quite rebellious. I didn’t like authority. I think that’s what he liked in me. As a child, I was naughty. Maybe because of my parents’ overzealousness.

Q. Weren’t you a good student?

A. It was the time of the Vietnam War and I spent more time protesting than studying. I remember my youth as an eternal protest: rallies, drugs…

Q. Drugs in school?

A. It was another era, with its difficulties and its advantages. I spent a third of my time at the university, another third protesting and the other third at MoMA [the Museum of Modern Art].

Q. After a few decades, you signed on to the expansion of that museum. Who took you there for the first time?

A. I went alone. My parents liked nature and sports. And I was fascinated by the modern world. I wanted to be a sculptor.

Q. How much freedom did you have in designing the MoMA expansion?

A. I know the museum by heart. I knew its problems: it was disconnected from the city. You had to walk half-a-mile before seeing any art. It was an unnatural, fake building — too crowded all the time.

Q. Do cities flourish when rents are cheap?

A. The New York of my youth was like that. Cheap rent gives you time to create, think and live. I spent the day on the street. That opened my mind a lot.

Q. Why did you end up becoming an architect?

A. I wanted to learn. From photography, I went to cinema; and from cinema, to architecture. To me, architecture seemed more capable of transforming, more capable of defending interdisciplinary ideas.

Q. The intersection between disciplines defines your work.

A. In the world of art, evidence — and even doubt — are welcome. Also intuition. In architecture, you spend the day giving explanations about why you do things.

Q. Have you felt that there’s a fear of what’s different in your professional world?

A. Fear is always harmful. And it always describes who expresses it more than who receives it. But we suffered because of it. We were artists for architects and architects for artists. Our work was dissident: it didn’t fit. Being in a no-man’s-land is a problem when it comes to getting scholarships or teaching jobs. However, as a woman, I believe that, by living in New York, I’ve benefited from what many struggled with before.

Q. Did you want to fit in?

A. We don’t work with a formula. We experiment, question, mix. We’ve been transgressors to expand the limits of architecture. And the architectural community took us for geeks.

Q. One of your first works was the Blur Building, built over the water in Switzerland. Can an experiment become a building?

A. I honestly think so. But those projects were temporary. Others are short-lived without having been designed to be short-lived. Austerity is often an excuse to avoid experimenting.

Q. Today, architecture is taught as a hybrid discipline.

A. We’ve always defended the mixture. We don’t know how to see it any other way.

Q. John Hejduk — who was your teacher — felt that the act of building corrupted architecture. Do you agree?

A. No. He believed that architecture was a discipline, not a profession. That’s why the education I received was to relate architecture to art, literature, creativity...

Q. Can you contribute to architecture without building?

A. Yes. By making laws, commissions and giving opportunities to others, cities are drawn up. For me, any way of creating space is architecture.

Q. Do you feel the need to make groundbreaking proposals?

A. It’s not about surprise, but about exploring.

Q. The High Line is the recovery of miles of old railway tracks, which have been converted into an elevated park. The project changed the life of the old structure.

A. It’s architecture that starts from the obsolete and protects nature. It has to do with our ability to adapt.

Q. And the ability to listen to local residents.

A. I had never heard what people were saying before. Getting out of the academic vision to do it changed my perspective. Following the attacks of September 11, New York was plunged into a wave of civility. We felt part of the same city. We needed to take care of her [the city] and take care of ourselves. This part of Manhattan was an empty, hopeless place: a perfect place for improvement.

Q. Are you in favor of consulting citizens about how the city should be?

A. It’s good to get out of your world, but it requires hours of meetings and listening. For me, the idea of transforming urban waste into a living part of the city was fascinating. It went from infrastructure to ruin, from ruin to garden and from garden to promenade.

Q. Is nature more powerful than culture?

A. Nature is culture. It’s not so much about building as about collaborating with nature. And with neighbors. And it cost more to remove the tracks than to maintain them. They were already covered with vegetation. In that neighborhood of New York [Hudson Yards], there were hardly any parks. The solution was to leave it almost as it was. And make it more secure. It touched a nerve that needed to be touched.

Q. That’s what artists do: they anticipate the future.

A. We’re so glued to our screens that seeing what was happening on the street was treated like a discovery!

Q. What did you learn by building?

A. That, in the effort, there can be a lot of creativity. [Thomas] Edison said it: “Genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.” Architecture is a team effort. A [building] permit matters more than a line. The biggest difficulties in architecture aren’t technical: they come from dealing with people.

Q. It’s easier to get a building to move...

A. Like The Shed. Well, yes. Technical problems are fun, challenging. Explaining to people that what is good for one resident is good for everyone is more difficult. But I like it — it’s the story of my life. My friends run from the fire and I run towards it.

Q. How come?

A. Where other people see defeats I see opportunities. I remember when we won the bid to expand Lincoln Center, Frank Gehry said: “Don’t touch it: these people are impossible.” And I thought: I’m going to prove him wrong. Of course, it took a lot of energy. I had to host a conference to explain our design. I showed six different options. It’s true: everyone is afraid of change.

Q. You don’t seem to be.

A. I treat it as an opportunity for growth. I came to New York at the age of five!

Q. Which of your projects has reinvented New York?

A. The expansion of Lincoln Center. The original Philip Johnson building was designed to be reached by car. Not ours. That marks the evolution of the city.

Q. What can the most intellectual type of architecture contribute to the parts of the world that have limited means?

A. It takes a lot of brainpower to deal with scarcity and chaos. The great architectural challenges are there: between the slowness [of construction], the high price of buildings and the urgent needs of the world.

Q. Did being an immigrant prepare you for austerity?

A. I don’t have an austere life. But I prefer one fabulous thing to a hundred good ones.

Q. What’s your relationship with money?

A. I spend a lot. But it doesn’t motivate me. I like the comfort and not having to worry about the solvency of the [architectural] studio. But I prefer freedom over money.

Q. Are you a free architect?

A. I’m a free person. I don’t have many things: no cars, no planes, no gold. My luxury is the freedom from having to do commercial assignments; not having a list of good jobs and others that simply pay the bills. That, to me, is being rich.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition