Art

Art History’s 8 Greatest Mysteries—from Stonehenge to Banksy

It’s the best-known painting in the world, and art historians are almost certain they know who it depicts. So why is there so much mystery surrounding the Mona Lisa?

The clue to its identity is thought to lie in Giorgio Vasari’s book The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), which gives a description of an artwork “for Francesco del Giocondo, the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife.” (The painting’s other famous moniker, La Gioconda, derives from both the feminine of Giocondo and from her legendary smile—Mona Lisa is “the jocund one.”)

An additional, more recent discovery adds weight to this hypothesis: A note written by one of Leonardo’s contemporaries, found in a manuscript margin and dated October, 1503, mentions the Renaissance artist working on a painting of Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo in the year he supposedly began work on the Mona Lisa. Yet over the years, other claims to its identity have proliferated: Does it, in fact, portray Leonardo’s mother? Or Renaissance-era marchesa and art patron Isabella d’Este? Or even Leonardo himself?

The emergence of all these theories can perhaps be accounted for by the simple fact that, as humans and art fans, we love mysteries. The study of artworks and objects of visual culture is a tantalizing exercise in unraveling the unknown. Here are eight lesser-known, but no-less-interesting, art-historical puzzles that have consumed budding art historians and experts for decades, even centuries.

Jiahu Symbols

c. 6000 B.C, Prehistoric China

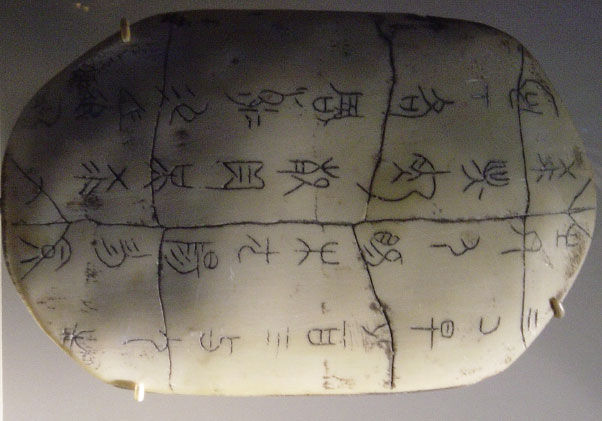

Replica of an oracle turtle shell with Jiahu script inscribed on it. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

In 2003, archaeologists excavating Neolithic graves in China discovered tortoise shells bearing markings—now known as the Jiahu symbols—that some believe to constitute the first known example of human writing, unseating Sumerian cuneiform (first used c. 3100 B.C.). Adherents to this theory have pointed to supposed similarities between the Jiahu symbols and the earliest accepted Chinese script, inscriptions on oracle bones from the Shang dynasty (c.1200–1050 B.C.).

Scholars have largely pronounced the symbols a form of “proto-writing” that lacks the linguistic component necessary to be a true text, though their visual resemblance to Shang script suggests that they might not be purely pictographic, either. Another question surrounds the connection between the Jiahu markings and Shang script—though visually similar, they are separated by some five millennia. However, the alluring possibility of having discovered the world’s first written language will surely motivate future Chinese archaeologists to continue to probe the secrets of the Jiahu symbols.

Stonehenge

c. 2500 B.C., Prehistoric England

Stonehenge. Photo by Wilfried Joh, via Flickr

Few artistic mysteries have captured the popular imagination like the prehistoric monument Stonehenge. The enormity of the site’s standing stones suggests that a tremendous amount of planning, coordination, and work must have been involved in its construction, prompting speculation as to how it was built and for what purpose. Was it the Druids? Well, no: The Celtic society that produced that enigmatic priestly caste didn’t exist for another two millennia.

The 12th-century British cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that the Arthurian wizard Merlin created the structure by means of magic or machinery, which certainly deserves our good-faith consideration. However, most modern scholars believe that Stonehenge, the stones of which have been radiocarbon dated, is a Neolithic ritual site within a large-scale burial complex that was likely constructed at great effort to align with certain astronomical events in the night sky—but without any written record to provide a clue, its purpose may always remain something of a timeless prehistoric mystery.

Mask of Agamemnon

c. 1550–1500 B.C., Ancient Greece

Mask of Agamemnon. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Dubbed “the Mona Lisa of prehistory” by Cathy Gere in her 2006 book The Tomb of Agamemnon, the so-called “Burial Mask of Agamemnon” was discovered at the ancient Greek site of Mycenae by German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in 1876. Schliemann determined that the face, the most spectacular of several hammered in gold and discovered in the royal shafts at Mycenae, must be that of the mythical Greek war hero Agamemnon—the king of Mycenae during the time of the legendary Trojan War. The discovery, in his estimation, effectively confirmed the mythic Trojan War as an actual historical event, and Schliemann announced that he had “gazed upon the face of Agamemnon.”

However, as it turns out, Schliemann was exaggerating somewhat. Previously, in 1870, he had excavated at a site in Turkey thought to correspond to Troy itself. Once he discovered the ruins and named the site accordingly, he compiled a cluster of artifacts he dubbed “Priam’s Treasure” after the mythical king of Troy, then smuggled them out of Anatolia, causing the Ottoman Empire to revoke his permission to dig and sue him for their cultural patrimony.

Schliemann would be monitored closely by the Greek Archaeological Society for the incidents at Troy, suggesting that the burial mask at Mycenae might not be a fabricated “plant,” yet dating of the mask indicates it comes from several centuries before the period of the legendary Trojan War—and thus Agamemnon. The mysteries of where Agamemnon’s bones lie, who was actually buried beneath this mask, and whether Schliemann had the mask fabricated to gain acclaim remain unsolved.

Villa of the Mysteries

c. 1st century B.C., Ancient Italy

Villa of the mysteries. Photo by Justin Ennis, via Flickr.

Mystery cults proliferated in the ancient Hellenistic world and were incorporated into the Roman Empire as a supplement to their other religious customs. Despite their recognition and relative acceptance, such cults were to be practiced only in private ceremonies, usually held in private homes. Though the secrecy of these congregations prohibits most knowledge of their activities and beliefs, wall paintings at the Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii—preserved by volcanic ash after the A.D. 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius as one of the greatest examples of ancient Roman painting—give a window into one group’s curious beliefs and practices.

Or rather, given that the Pompeiian residence in question housed a Bacchic cult, what we’ve been left with is a small window into their libations. The murals of the so-called Room of the Mysteries give the most complete extant imagery of a young noblewoman undergoing initiation into one such group and greatly helped excavators fill gaps in their knowledge about this shrouded corner of Roman religious life. While scholars understand many general things about private Roman mystery cults, the specific acts in these murals were a revelation.

Nazca Lines

c. 500 B.C–A.D. 500, Ancient Peru

Nazca Lines. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

From the highest hills of ancient Nazca (or Nasca, as the name of the ancient indigenous group is sometimes spelled) lands in southern Peru, one can view giant geoglyphs that are seemingly carved into the earth itself. Llamas, monkeys, spiders, and fish—these forms were represented by Nazca artists who turned over the red, oxidized rocks of the pampas to reveal the lighter ground beneath them. Their enormity and exactitude, as well as the fact that they are designed to be viewed from directly above, have mystified researchers bent on determining how and why they were made.

The question of how is less contentious: With some planning, relatively simple tools, and rudimentary surveying equipment like ropes and stakes (stakes were found at the site), the Nazca people could have created these monumental earthworks. But the question of why lingers. Were they images meant only for the gods to see? Do they correspond to constellations or align with astronomical events like Stonehenge, or certain indigenous ritual sites throughout the Americas?

One theory suggests that the geoglyphs and long lines that connect them correspond to underground water tables necessary to the continuation of the Nazca people. Archaeologists and anthropologists continue to study the lines—having found new figures as recently as 2016—in an effort to answer these questions.

The Moai of Easter Island

c. 1250–1500, Polynesian Chile

Moai. Photo by RS, via Flickr.

When the Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen landed at Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in 1722, the tiny island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean only had an estimated 1,500–3,000 inhabitants, but it also housed over 800 monumental statues of simplified human figures. Whoever created the moai, as they are called, quarried the stone for the totemic figures at the volcanic crater Rano Raraku, carved the statues on-site, then transported them over land to stand along the coast, looking inward across the island.

This represents an extraordinary undertaking, as the moai are 13 feet tall and weigh, on average, 14 tons each. Several hundred still exist in some unfinished state in the quarry, with the incomplete “El Gigante” topping out at 72 feet tall and approximately 145–165 tons.

When the British explorer James Cook brought a Polynesian crew member to the island, he was able to communicate roughly with the Rapa Nui and discovered that the statues commemorated deceased high chiefs, though these monuments almost certainly convey additional significance or meaning.

Scholars concerned with the mystery of how the Rapa Nui transported the massive moai from quarry to shore have a more difficult time. For years, theories that ropes were used by teams of people to pull the moai over logs or on wooden slides held the greatest sway, though the archaeological record has now convinced many scholars that the statues were (amazingly) erected at the quarry and “walked” to their locations by rocking them side to side and pulling them forward with ropes.

Caravaggio, The Beheading of St. John the Baptist

1608, Malta

Caravaggio, The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, 1608. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most acclaimed masters of the Italian Baroque, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio is remembered both for his dark, dramatic compositions, with their powerful use of light, and his sometimes darker, even more dramatic life. In 1606, he killed a young man in an altercation in Rome—some say the hot-headed painter murdered him in a duel over a bet, or even a tennis match—but his intentions and the circumstances of the event are largely unknown.

Caravaggio fled to Naples, then Malta, and in 1608 completed the only painting he would ever sign, his The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, commissioned by the Knights of Malta as an altarpiece. Differing from his earlier paintings of Salome and St. John the Baptist, which always took place in the dramatic aftermath of the violence and typically featured a close-up of the victim’s head, his Beheading altarpiece placed the biblical event in everyday terms, creating a distancing effect.

In the wake of his own killing, Caravaggio depicted St. John being murdered in the street like a common man and placed his signature in the martyr’s blood—all of which has led certain scholars to ask: Did Caravaggio compose this painting as a secret admission of guilt? The mystery continues, and like the case of Caravaggio’s deadly incident in Rome, the evidence remains largely circumstantial.

Banksy

c. 1993–present, United Kingdom

Photo by R, via Flickr.

It would be hard to write about art history’s great unknowns without a nod to the fact that one of the most famous living artists is virtually unidentifiable. Though the street artist Banksy has been creating art since the early 1990s—nearly three decades—the artist has guarded his or her identity closely, despite working on high-profile projects like the Academy Award-nominated 2010 documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop.

Banksy’s graphic, stenciled style is so instantly recognizable as to make the question somewhat moot. There is something distinctly Duchampian to the enterprise of hiding one’s identity: Do we need to know who Banksy is? Why? Would it matter if Banksy were a collective? Is the artist even British?

It would at least seem we can count on that last query. Let’s bring this full-circle: Banksy was honored with a place in the Arts category of “Greatest Britons 2007,” a one-time awards show in May of that year, despite the issue of the artist’s unknown identity. In June 2007, Banksy humorously built a “Stonehenge” out of portable toilets at England’s Glastonbury Festival—coincidence, or a millennia-spanning wink at his status as the latest, greatest mystery of British art?

Jon Mann

No comments:

Post a Comment